The Prevalence of Mental Health Disorders Among Latino Parents

May 19, 2022

Research Publication

The Prevalence of Mental Health Disorders Among Latino Parents

Author

Overview

This brief was modified on May 27, 2022 to provide additional context for how we attempted to best reflect the complex status of the Puerto Rican population in our analysis and in the text and to correct a technical error in the numbering of the references.

Addressing Latino parents’ mental health needs is critical to supporting their families’ well-being. Parents’ mental health can affect multiple aspects of family life, including their ability to secure and maintain employment and provide financially for their family, the health and stability of couples’ relationships, and the quality of parent-child interactions.1,2,3,4 To adequately support parents who face mental health disorders, researchers and mental health professionals need information about the prevalence of mental disorders among Hispanic parents specifically, and how this prevalence varies among Latinoa subgroups.

This brief uses data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III (NESARC-III), a nationally representative sample of the United States civilian population ages 18 and older, to describe the prevalence of mental health disorders among Hispanic parents of children under age 18—measured by the prevalence of having ever experienced major depression, anxiety, substance use, or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and having ever attempted suicide. Unlike many national surveys that collect limited information about a select number of mental health indicators, the NESARC-III collects detailed information about mental health symptoms to derive clinical diagnoses of mental health disorders.

We also examine the variation in prevalence of mental health disorders within the Latino parent community by place of birth (U.S. state-bornb versus non-U.S. state-born) and heritage (country of origin). Because of differences in the distribution of non-U.S. state-born versus U.S. state-born Hispanics within heritage, we examine heritage and place of birth jointly to understand whether differences in the prevalence of mental health disorders by heritage are maintained after considering differences by place of birth. We conclude by discussing strategies for improving access to mental health services for Hispanic parents of children under age 18.

Key findings

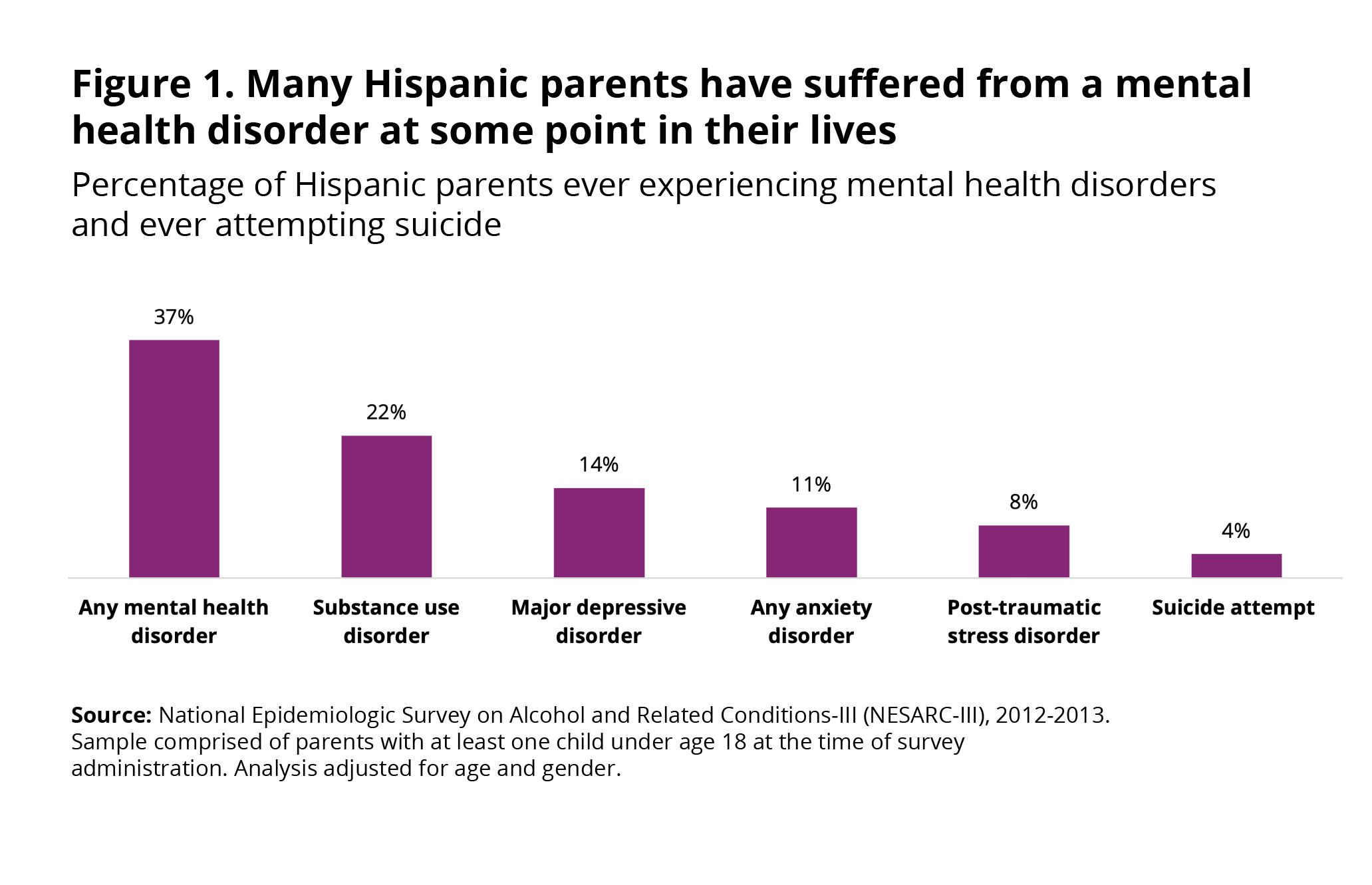

- Over one third (37%) of Latino parents have experienced a mental health disorder—depression, anxiety, substance use disorder, or PTSD—at some point in their lives. The prevalence of mental health disorders was lower among Hispanic parents than among non-Hispanic parents. Among Latino parents with children under age 18:

-

- Twenty-two percent experienced a substance use disorder at some time in their lives.

- Fourteen percent experienced major depression.

- Eleven percent had an anxiety disorder.

- Eight percent experienced PTSD.c

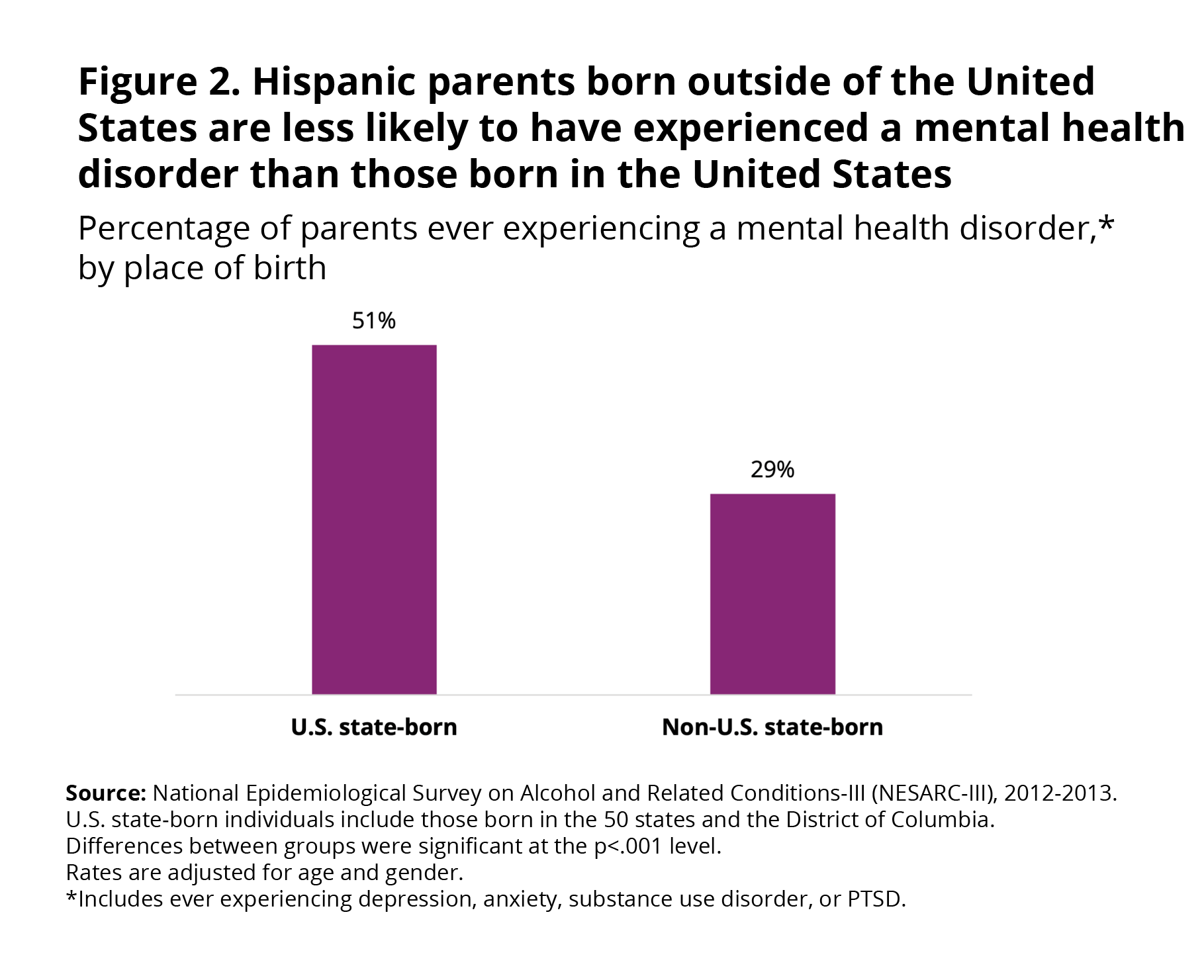

- Hispanic parents who were born outside of the 50 states had a lower prevalence of mental health disorders than Latino parents born in the 50 states. Twenty-nine percent of non-U.S. state-born Hispanic parents had experienced a mental health disorder, compared to 51 percent of U.S. state-born Latino parents.

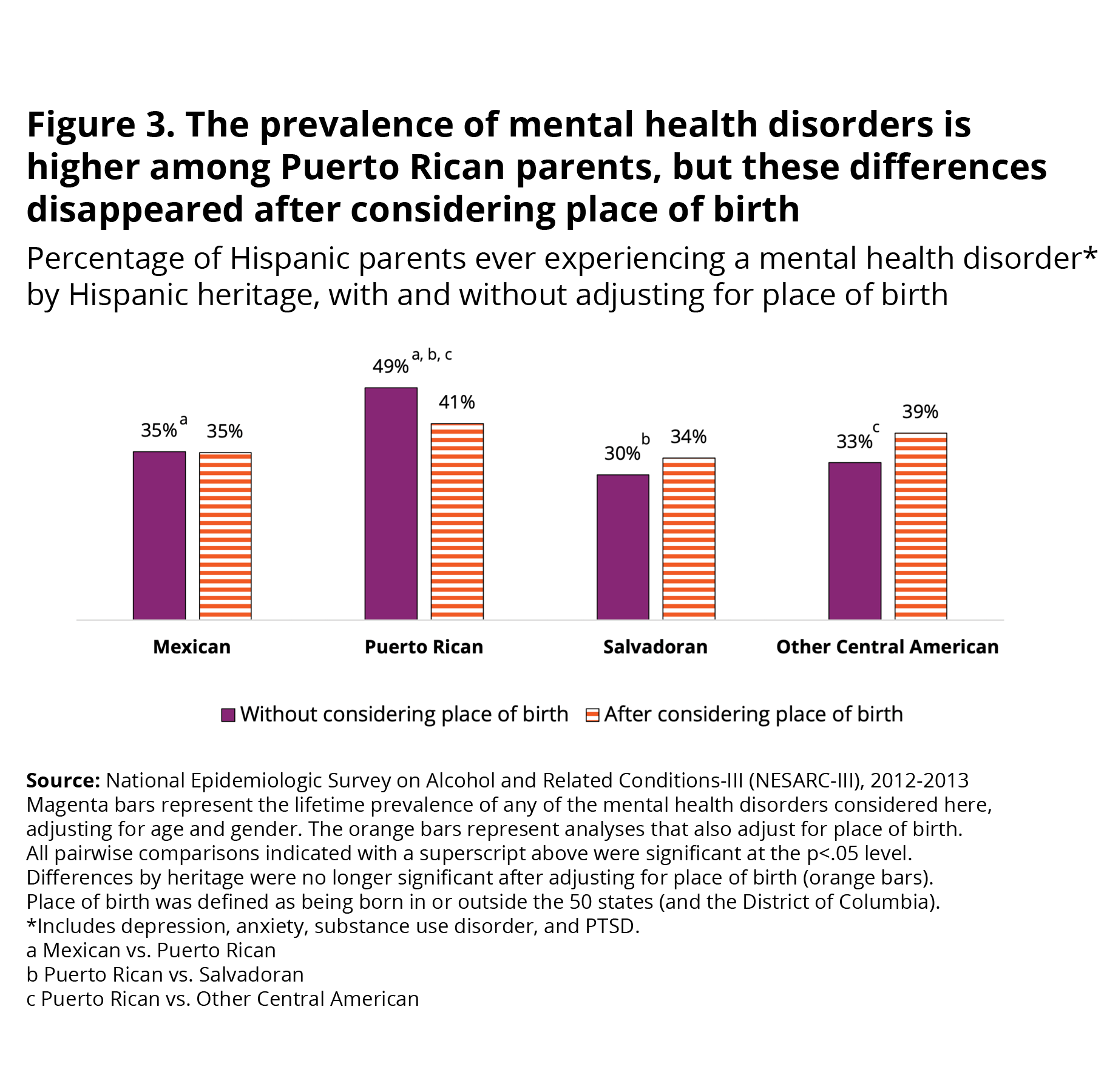

- Parents of Puerto Rican heritage were more likely to have experienced a mental health disorder at some point in their lives than parents whose ancestry was from Mexico, El Salvador, or other Central American countries. However, differences by heritage were no longer present after adjusting for place of birth.

NOTES TO THE READER

Mental health terms used in this brief: Multiple terms can describe an individual’s challenging feelings, thoughts, moods, and behaviors (e.g., mental health disorders, mental illness, psychiatric disorders, mental health problems, and psychological issues). These terms may have different meanings and interpretations. In this brief, we use the term “mental health disorders,” which reflects that the mental health problems reported met the criteria for a clinical diagnosis of a mental disorder (e.g., major depressive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder). The clinical diagnosis of a mental health disorder requires that symptoms reach a level of severity that interferes with an individual’s social, family, or work life. This terminology is consistent with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, the standard used by mental health professionals in the United States to assess and diagnose mental health disorders.

Our approach to reflecting the complex social position of the Puerto Rican population in our analysis: Puerto Rico is an unincorporated territory of the United States with commonwealth status. Individuals born in Puerto Rico are U.S. citizens and, as citizens, are able to freely move from the island to the 50 states (and to the District of Columbia, hereafter referred to as the 50 states), making their immigration experience different from that of other Latin American individuals. However, the experience of living on the island—politically, socially, and culturally—substantially differs from that of living in one of the 50 states. Despite their citizenship status, Puerto Rico residents are not conferred the same rights as other U.S. citizens, including Congressional representation, the right to vote in presidential elections, and access to certain federal benefits as individuals residing in the 50 states.

Furthermore, a strong cultural identity among Puerto Ricans and the use of the Spanish language on the island means that Puerto Ricans moving from the island to the 50 states go through an acculturation process, and associated acculturation stress. These experiences are more similar to the experiences of a Latin American moving from their home country to the United States than to the experiences of an individual moving from one state to another one. Such experiences can also affect the mental health of individuals. Indeed, the prevalence of mental health disorders among Puerto Rican individuals living in the 50 states is significantly higher than among those living on the island. For these reasons, when we examine differences in the prevalence of mental health disorders by place of birth, we distinguish between those born in and outside of the 50 states.

We acknowledge that the decision of how to classify island-born Puerto Ricans is complex and should consider multiple positionalities (race, class, ethnic identity, etc.) and contexts (political, cultural, migration, etc.) that shape the Puerto Rican experience. This decision should be driven, in part, by the research question being addressed. In this case, where our focus is on mental health, we considered it important to recognize the varied experiences of Puerto Rican parents who were born on the island relative to those born in the 50 states, and to prioritize an untangling of the role of acculturation—especially given its implications for mental health.

Additional Context

While many children whose parents have experienced a mental health disorder go on to have healthy lives, the presence of a mental health disorder in parents can increase the child’s risk for negative emotional, cognitive, behavioral, and physical health outcomes during childhood and later in life. 4,5,6,7 These risks are attributed to a mixture of genetic, biological, and environmental factors (e.g., less supportive parenting, stressful home environments, environmental risks shared by parents and their children).8,9,10,11

Mental health disorders are common in the general population, but most individuals respond well to treatment.12 However, mental health care remains difficult for racial and ethnic minority groups to access, which represents a significant health inequality that has only grown over the years.13 Hispanic populations, in particular, face multiple barriers that limit their access to mental health care and treatment.14,15 For example, only 6 percent of licensed psychologists in the United States are able to provide mental health services in Spanish,16 and just 61 percent of Latino adults in the United States speak English “very” or “pretty” well—creating a mismatch between potential demand for, and supply of, linguistically appropriate mental health care.17 Further, Latino individuals in the United States have limited access to culturally responsive services that reflect an understanding of their cultural norms, immigration, trauma and acculturation experiences, variation in the presentation of mental health symptoms, and the history of stigma and mistrust of the mental health field among Latino communities.18,19,20,21

The Latino population is diverse in terms of heritage, languages spoken, migration histories, traumas encountered, catalysts for migration, and experiences of and levels of exposure to U.S. culture.22,23 These differences can affect Latino populations’ mental health outcomes and their level of access to mental health services.24,25,26 For example, notable differences in physical and mental health have been observed between Latinos born in the United States and those born outside of the United States, with immigrants showing better outcomes.27 Similarly, the mental health outcomes of Hispanic populations seem to differ by Latino heritage (e.g., Mexican, Puerto Rican, Salvadoran),27 but these comparisons are not commonly examined due to limitations in sample sizes. Identifying how mental health disorders vary across different groups of Latino parents allows researchers and mental health professionals to understand the needs of different subpopulations and target culturally responsive mental health services.

Data and Methods

This brief uses data from the 2012-2013 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III (NESARC-III),28 the most recent national dataset containing detailed information about lifetime prevalence of metal health disorders, a sizeable Latino sample, and various indicators of Hispanic diversity. The NESARC-III is a nationally representative sample of the noninstitutionalized adult population ages 18 and older in the United States (N= 36,309). It includes individuals in the 50 states and the District of Columbia who reside in households and selected group quarters (e.g., group homes). Individuals living in U.S. territories, including Puerto Rico, were not included in the sample. Hispanic, Black, and Asian individuals were oversampled.

Bilingual interviewers conducted interviews in Spanish when needed, and participants could toggle between the two languages as desired. While recruitment, screener, and interview materials were all available in Spanish, screenings to select individuals into the study were conducted in Spanish only in households in which members exclusively spoke Spanish. This may have resulted in an underrepresentation of Hispanic individuals who speak some English but are more comfortable speaking Spanish.

The NESARC-III collected detailed information about mental health using the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule (AUDADIS-5),29 a fully structured diagnostic interview administered by laypersons to assess mental health disorders according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5).34 The NESARC-III also collected information on several indicators of Hispanic diversity, including individuals’ country of birth and ancestry. This allowed for the examination of potential differences between different Latino heritage groups.

Our analyses focused on Latino parents who had at least one childd under age 18 living in the household (n= 2,727). This sample included parents at all income levels. When we analyzed only parents with annual household incomes below 200 percent of the federal poverty threshold, our findings were similar to those from the entire sample. Therefore, for simplicity, this brief only reports findings from across all income groups.

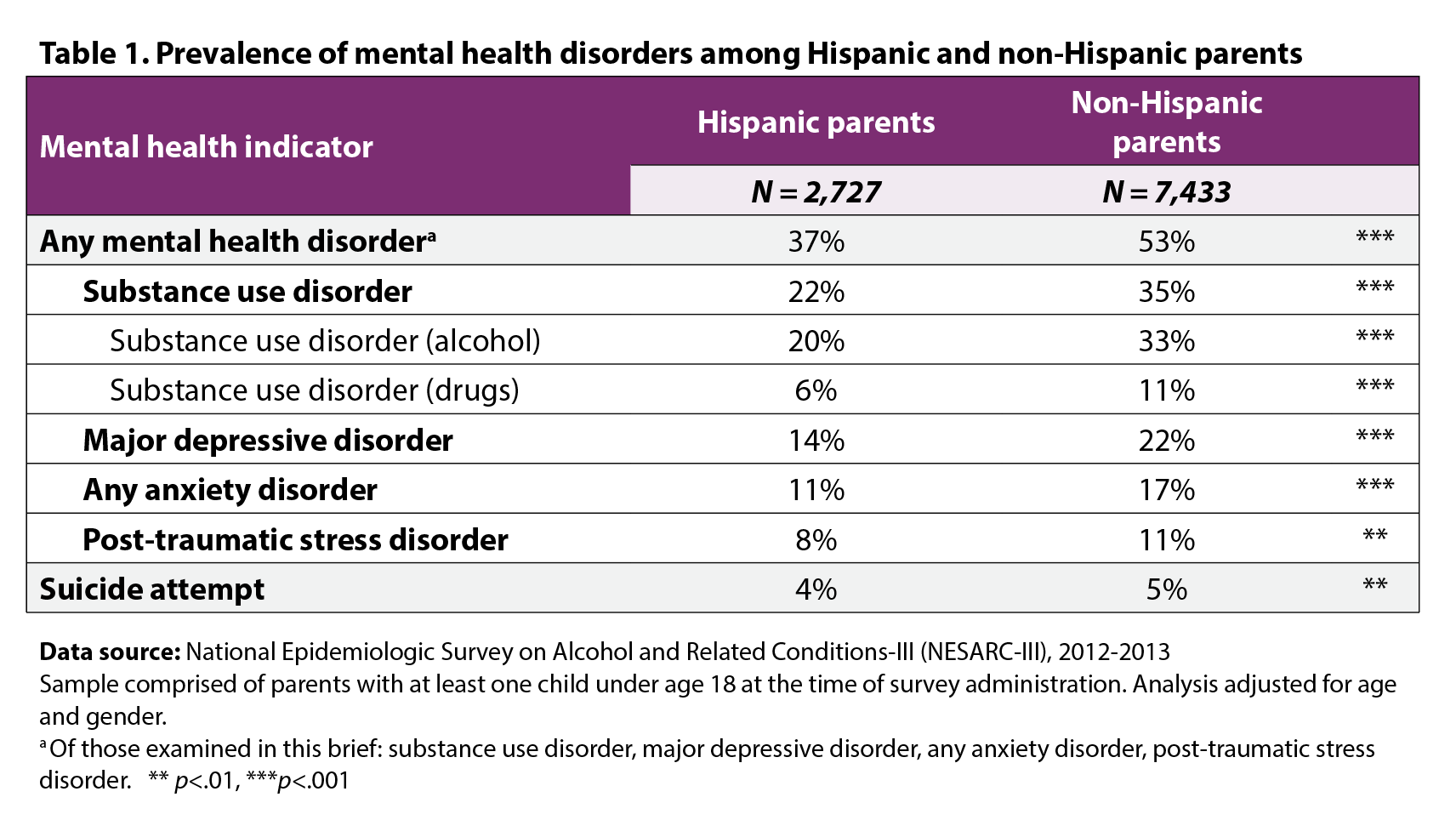

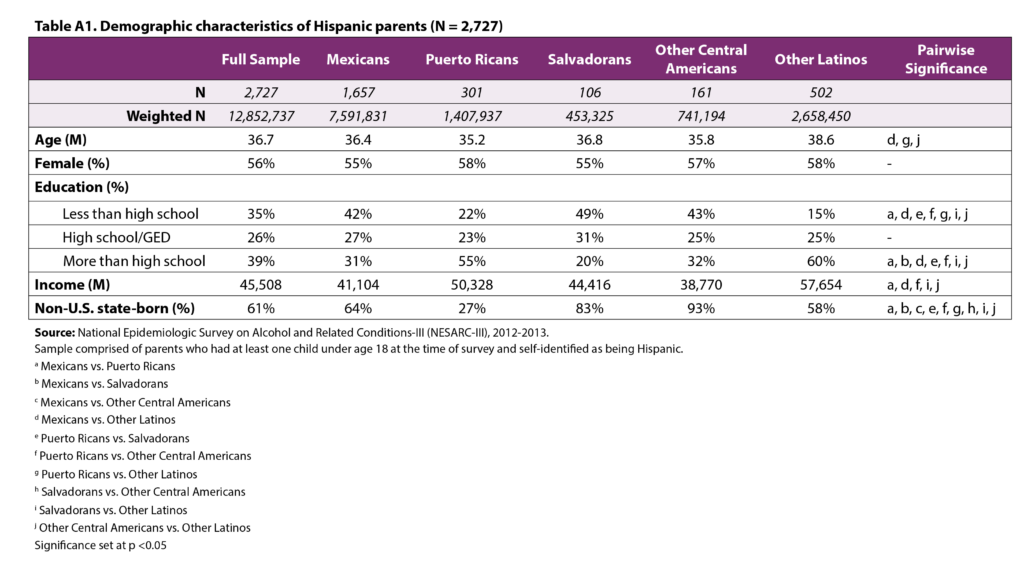

We first examined the demographic characteristics of the sample and explored variation by heritage (see Appendix A). Next, we estimated the lifetime prevalence of each mental health indicator using logistic regressions that adjusted for parent age and gender. We focus on the lifetime prevalence (as opposed to current prevalence) of the disorders because there is strong evidence that children may inherit a vulnerability for mental health disorders through their genes,9 and because once a person has experienced a mental health disorder, there is a high chance that they will experience it again later in life.30,31 Even though the goal of the present study was not to compare the prevalence of mental health disorders across different racial and ethnic groups, we provide the adjusted prevalence of each mental health indicator examined here among parents of all other racial and ethnic groups (excluding Hispanic parents) in Table 1 to provide context for our findings (n= 7,433).

We then examined whether the prevalence of “any mental health disorder” (of those examined here) differed by place of birth (born in, versus born outside, the 50 states and the District of Columbia) and heritage in separate models. We subsequently reexamined the differences in prevalence rates of any mental health disorder by heritage after accounting for variation in place of birth. In our examination of differences by Hispanic heritage, we excluded the “Other Latino” group. This group included Latino parents from heterogeneous backgrounds, and we did not consider comparisons with this group to be meaningful. We used pairwise t-tests to evaluate whether the differences in proportions between subgroups (based on place of birth and Hispanic heritage) were statistically significant.

All analyses adjusted for age and gender, applied sampling weights to represent the U.S. population according to the 2012 American Community Survey,32 and accounted for the complex survey design as recommended by the NESARC-III.33 Analyses were conducted using Stata version 17.

Definitions

Mental health disorders. Participants completed the Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule (AUDADIS-5) with a trained interviewer to determine whether they have ever met the criteria for a mental health diagnosis. A mental health diagnosis requires that participants endorse specific symptoms, sufficient duration of these symptoms, and severity of symptoms as specified in the DSM-5,34 the manual used by mental health professionals to diagnose mental health disorders. All mental health diagnoses require that the symptoms significantly impair or interfere with the individual’s daily life. This procedure allowed us to determine whether a study participant meets the criteria for each of the mental health diagnoses we examined, regardless of whether they had received an official diagnosis from a provider. For the current study, we created categories of the most common mental health disorders:

- Substance use disorders are mental health disorders characterized by using drugs or alcohol in a larger quantity or duration than intended, often in the face of a persistent desire to cut down or control use. Other potential symptoms include cravings; continued use even when the substance causes social, interpersonal, and professional problems; giving up social, occupational, or other activities because of use; requiring greater amounts of drugs or alcohol to achieve intoxication; and experiencing withdrawal. Substance use disorders include a diagnosis of alcohol, sedative, cannabis, opioid, cocaine, stimulant, hallucinogen, inhalant/solvent, club drugs (e.g., ecstasy, roofies), heroin, or other drug use disorder.

- Major depression is primarily characterized by a depressed mood (e.g., feelings of sadness, hopelessness, emptiness) and a significant loss of interest in previously pleasurable activities for at least two consecutive weeks. Other symptoms include significant weight loss or gain, changes in sleep patterns, fatigue, feelings of worthlessness and guilt, difficulty concentrating, and thoughts of death or suicide.

- Anxiety disorders are characterized by excessive worry that is difficult to control and results in feelings of being on edge, restlessness, fatigue, difficulty concentrating, irritability, and sleep difficulties. Participants were identified as having an anxiety disorder if they met the specific criteria for any of the following disorders: generalized anxiety disorder (characterized by a worry about a number of different things), panic disorder (experienced by those who have sudden panic attacks and worry about experiencing those), specific phobias (fear of a specific object, place, or situation), or social phobias (fear about social interactions).

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) describes a cluster of symptoms that can occur after experiencing a traumatic or life-threatening event that causes significant impairment. These symptoms include experiencing flashbacks, significant psychological distress, intrusive thoughts or reminders about the event, avoiding reminders of the event, hypervigilance, and sleep disturbance. The current study uses a broad definition of PTSD as outlined in the NESARC-III dataset. The broad PTSD diagnosis reflects the definition of the diagnosis from the DSM-5 but specifies that a diagnosis can be with or without impairment or distress and with or without duration of one month or more.

- Any mental health disorder was a variable created to indicate whether a participant had experienced any of the four categories of mental health disorders discussed above.

Suicide attempts. Participants were asked if they had ever attempted suicide.

Heritage. For participants born outside of the United States, we used their place of birth as their heritage. For those born in the United States, we used participants’ responses to the question, “Which country … best describes the heritage or ancestry you identify with?” We created five categories of Latino heritage: Mexican, Puerto Rican, Salvadoran, Other Central American, and Other Latino. The first three groups represent the three largest Latino heritage subgroups in the United States.35

Place of birth. Place of birth refers to whether the participant was born in, or outside, the 50 states or the District of Columbia. Rather than using broad categories that distinguish between those born in or outside of the United States (e.g., foreign-born vs U.S.-born), we specify that we are comparing those born in or outside the 50 states or the District of Columbia to clarify our approach to handling the complex situation of individuals who were born in Puerto Rico. Puerto Rican individuals born in Puerto Rico are U.S. citizens, as Puerto Rico is an unincorporated territory of the United States with commonwealth status. However, there are substantial cultural differences between the continental 50 states and Puerto Rico that—combined with a strong national identity—make the experience of living in Puerto Rico versus living in the 50 states similar to that of living in a Latin American country versus the 50 states.36 This is further supported by the fact that Puerto Ricans moving to the mainland go through an acculturation process, and associated acculturation stress, much the same as other immigrants from Latin America.37 Therefore, as is often done in studies that examine Latino immigrants, participants born in Puerto Rico were not included among those born in the United States, but rather were coded as non-U.S. state-born.25

Findings

Prevalence of mental health disorders and suicidality

In this section, we describe the prevalence among Hispanic parents of children under age 18 of ever experiencing major depression, anxiety disorders, substance use disorders, PTSD, and any of these disorders, as well as the prevalence of ever attempting suicide. While we first report prevalence rates for all Hispanic parents with children under age 18 in the household, we also present prevalence rates for non-Hispanic parents for context and comparison.

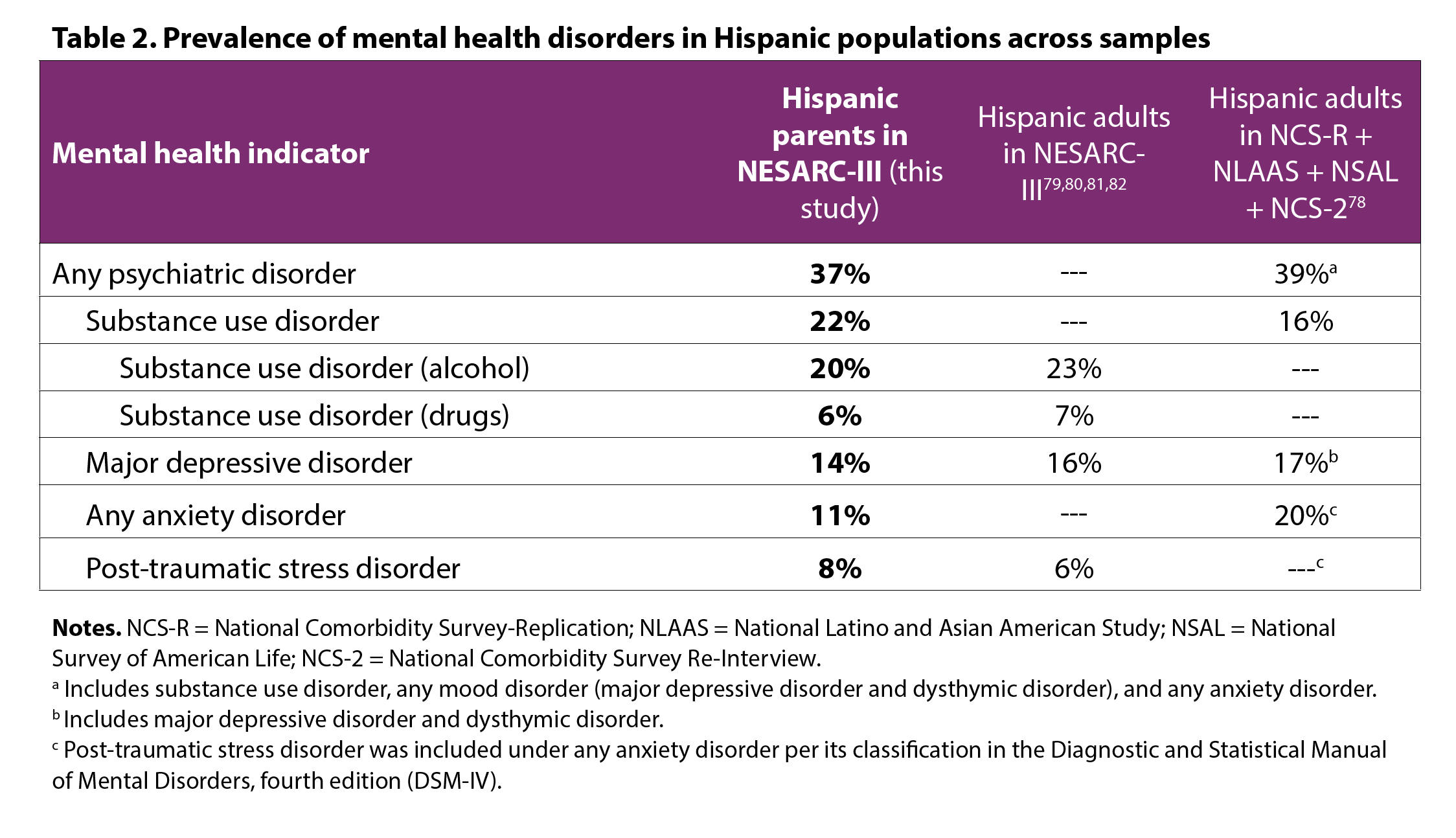

More than 1 in 3 (37%) Hispanic parents reported experiencing a mental health disorder at some point in their life (Figure 1). Of the mental health diagnoses examined for this study (depression, anxiety, substance use, or PTSD), substance use disorder was the most commonly observed mental health disorder, with 22 percent of Latino parents meeting the criteria for a diagnosis. Most of the substance use disorders were related to alcohol use disorder (Table 1): The prevalence of alcohol-related substance use disorder was 20 percent, whereas the prevalence of drug-related substance use disorder was 6 percent. Major depression was the second most common mental health disorder, affecting 14 percent of Latino parents. About 1 in 10 Hispanic parents met the criteria for an anxiety disorder (11%), and 8 percent had ever suffered from posttraumatic stress disorder. Four percent of Latino parents reported having attempted suicide at some point in their lives. Notably, the prevalence of all examined mental health disorders was lower among Hispanic parents than among non-Hispanic parents, as was the prevalence of suicidality (Table 1).

Prevalence of any mental health disorder by place of birth and heritage

Prevalence by place of birth. When comparing the prevalence of any mental health disorder (substance use disorder, major depression, anxiety, or PTSD) by place of birth, we find that the prevalence of mental health disorders was significantly greater among U.S. state-born Hispanic parents (51%) than among non-U.S. state-born Hispanic parents (29%) (Figure 2).e

Prevalence by heritage. Figure 3 shows the prevalence of ever experiencing any mental health disorder by heritage (Mexican, Puerto Rican, Salvadoran, and other Central American). Because the groups differed in the proportion of parents who were U.S. state-born versus non-U.S. state-born (see Appendix A), and the prevalence of mental health disorders varies by place of birth, we examined differences by heritage before and after considering differences by place of birth between the groups.

We found that, prior to considering differences by place of birth, the prevalence of mental health disorders varies by heritage: Puerto Rican parents were more likely to meet criteria for a mental health disorder (49%) than parents with Mexican (35%), Salvadoran (30%), or other Central American (33%) ancestry (see Figure 3).

However, adjusting for differences in rates of U.S. state-born and non-U.S. state-born parents across the four heritage groups resulted in reduced differences in the prevalence of mental health disorders, and a loss of statistical significance (see Figure 3). In other words, the prevalence of any mental health disorder did not vary by heritage after factoring for place of birth.

Analyses of past year prevalence show similar patterns by heritage and place and birth

One limitation of lifetime prevalence rates of mental disorders based on retrospective reports is that they rely on recall and likely underestimate the actual prevalence of disorders.38 We conducted ancillary analyses examining past year prevalence of disorders and found the same pattern of results as those reported with lifetime prevalence (available upon request). Briefly, the past year prevalence of any mental health disorder among Hispanic parents was 25 percent; the prevalence of past year mental health disorders was higher among those born in the 50 states and those from Puerto Rican ancestry, but differences by heritage disappeared after considering place of birth.

Summary and Implications

This brief has explored the prevalence of mental health disorders among Hispanic parents living with children under age 18, as well as variation in prevalence across place of birth and Hispanic heritage. We found that many Hispanic parents (37%) have experienced a mental health disorder in their lifetime, including depression, anxiety, substance use disorder, or PTSD.

Notably, mental health problems were less common among Hispanic parents than among their non-Hispanic peers, over half of whom had suffered from a mental health disorder at some point in their lifetime. The relatively lower prevalence of mental health disorders among Hispanic parents is remarkable considering their high exposure to socioeconomic adversity, social exclusion, and discrimination.39, 40, 41 Nevertheless, Hispanic populations face significant barriers to accessing mental health services. Factors contributing to racial and ethnic disparities in access to care include structural barriers (e.g., cost of care, lack of health insurance, availability of services, supply of Spanish-speaking mental health providers, transportation, lack of access to information about mental health and available services), attitudinal barriers (e.g., stigma, mistrust), and low perceived need of treatment among Hispanic populations.14,15,42As a result, many Hispanic adults who need mental health services do not receive them, particularly if they are immigrants.14,26

Improving access to mental health services among Latinos involves investing in the growth and diversification of the mental health workforce43 and implementing alternative models for mental health care to address additional barriers to care among Latino parents. The promotoras and peer supporter models, for example, offer promise in providing access to mental health supports for underserved communities that face language and cultural barriers to accessing mental health care.44,45 Promotoras are community members trained to become community mental health workers who provide support and access to resources and traditional mental health services for individuals who need them.44 As members of the communities they serve, promotoras understand the language and cultural values of individuals who come to them for help, which may reduce barriers associated with the stigma surrounding traditional mental health services.46 Similarly, peer supporters are individuals with similar lived experiences to the communities they serve, who act as a less formal point of entry for mental health support by conducting screenings and assessments, connecting individuals with additional resources, and offering crisis intervention.45

Other promising approaches that can improve access to mental health services among Hispanic parents include:

- Increasing parental knowledge about mental health and reducing stigma47,48,49,50

- Integrating mental health services into primary care 51

- Expanding telehealth services52

In recognition of the profound influence of parents’ mental health on child and family well-being, many government and community programs that serve children and families—such as Head Start, Healthy Marriage and Relationship Education programs, home visiting, and the child welfare system—integrate mental health care by providing services to families directly or by encouraging service providers to provide referrals to mental health care.53,54,55,56 Failure to address parents’ mental health needs can reduce the effectiveness of parenting, early care and education, employment and training, and similar programs that aim to support parents and families.

We also found that the burden of mental health disorders is not equally distributed among all Hispanic parents. In particular, the prevalence of mental health disorders is higher among Hispanic parents who were born in the 50 states and among Puerto Rican parents, who were more likely to have been born in the 50 states than Hispanic parents from other heritage groups. Notably, differences in the prevalence of mental health disorders by heritage were no longer significant after factoring for place of birth. A higher prevalence of mental health disorders among Hispanic populations born in the 50 states relative to those born outside of the 50 states is consistent with the “immigrant paradox.” This finding is often attributed to a number of factors, including a loss of culturally specific protective values with increasing acculturation, the intergenerational effects of structural racism and discrimination, and selection factors that distinguish those who migrate to the United States from those who do not (those who migrate are healthier and therefore have better outcomes).25

Because the Hispanic population’s background and experiences are so diverse,21 the mental health field must provide culturally informed, culturally responsive, and culturally sensitive care that recognizes this diversity. To improve cultural competence, providers should learn about cultural norms and worldviews of different groups; the structural and historical factors that affect families’ risks, trauma experiences, and help-seeking behavior (e.g., structural racism and anti-immigrant sentiment in communities, the labor market, and in the nation’s immigration laws); variations in the presentation and description of mental health symptoms; and the history of stigma and mistrust of the mental health field in racially and ethnically minoritized groups.57,58,59,60 Importantly, this learning process requires providers to recognize that the Latino population is diverse in terms of immigration status and context for migration, community histories, adversity and trauma exposure, acculturation levels, language use, familiarity and access to services and resources, and cultural practices.22,26,61,62

Culturally competent care has been shown to increase the effectiveness of mental health services.57,63 Mental health service providers who work with Hispanic populations should integrate knowledge gained about the different populations they serve into their practice.59 For example, investing time in building rapport and engaging with Hispanic clients is critical for building trust among Hispanic populations in general. However, providers who work with clients who are unauthorized immigrants should be aware of this population’s fear of disclosing personal information, and should offer reassurance of confidentiality early and often.59 Similarly, involving the family in treatment is often recommended when providing services to Hispanic populations given the centrality of the family in Latino culture.59 This approach might be especially beneficial among families who have experienced migration-related family separations and subsequent reunification. These families would also likely benefit from culturally responsive trauma‑informed services.59

Integrated services across sectors such as health care, home visiting, early care and education, and safety net programs are needed to support the overall well-being of Hispanic families. While increasing access to culturally appropriate services is an important step in addressing the mental health needs of Hispanic parents, it is important to recognize that mental health problems do not occur in a vacuum. Many Latino families are exposed to multiple stressors, including poverty, housing and food insecurity, and lack of health insurance, among many others.64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71 Many of these stressors have been exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic,72 with implications for the mental health of the Latino population.73 To support parents’ mental health, programs and policies need to address the multiple sources of stress that many Latino families experience, and which contribute to their mental health challenges.

How do the rates of mental health disorders found in our study compare to rates from other studies?

The prevalence of “any” lifetime mental health disorder among Hispanic parents in our sample is similar to that of Hispanic adults in studies with nationally representative samples using structured interviews to derive clinical diagnoses (Table 2). The lifetime prevalence of any mental health disorder among Hispanic adults across four major national studies—the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication (NCS-R),74 the National Latino and Asian American Study (NLAAS),75 the National Survey of American Life (NSAL),76 and the National Comorbidity Survey Re-Interview (NCS-2))77—was 39 percent.78 When considering specific mental health disorders, our findings for Hispanic parents are aligned with what others have found among Hispanic adults in the NESARC-III: 16 percent had suffered from major depressive disorder,79 23 percent had ever had an alcohol use disorder,80 7 percent had ever had a drug use disorder,81 and 6 percent had experienced PTSD.82 However, these prevalence rates are somewhat discrepant from those reported in the pooled sample referenced above, which found anxiety disorders to be the most prevalent mental health disorder (20%), followed by mood disorders (which include major depressive disorder and dysthymic disorder, a chronic form of depression; 17%), and lastly, substance use disorder (16%).

Discrepancies in prevalence rates across studies is likely due to a confluence of factors that include differences in the diagnostic interviews used (the NESARC-III used the AUDADIS-5 whereas the other studies used the World Health Organization World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WHO WMH-CIDI))83 and differences in diagnostic criteria used in different versions of the DSM (the DSM-5 for the NESARC-III and DSM-IV for other studies). Differences in the classification of disorders across versions of the DSM also explain why PTSD was previously considered an anxiety disorder (likely increasing the prevalence of “any anxiety disorder” in previous studies) and is now classified as a trauma and stress-related disorder,84 and is therefore examined separately. Similarly, the pooled analyses combined major depressive disorder and dysthymic disorder to examine mood disorders more broadly, which may explain the lower prevalence of major depressive disorder in our sample. Order effects likely played a role in explaining a higher prevalence of substance use disorder in our sample. The NESARC-III interview asked about substance use at the beginning of the interview, whereas studies using the CIDI asked about depression and anxiety first. Participants completing diagnostic interviews are more likely to endorse items, and to meet diagnostic criteria, in modules that appear at the beginning of the interview compared to those that appear later on.85 This is possibly because, as participants become acquainted with the interview, they come to realize that positive responses to questions lead to further questions. Thus, there is a motivation to respond “no” to subsequent stem questions to shorten the length of the interview.85 Taken together, variability in prevalence rates across studies is expected; these prevalence rates should be considered a range of possible values observed in the population and later summarized through meta-analytic techniques.

Footnotes

a In this brief, we use the terms “Hispanic” and “Latino” interchangeably.

b The term “U.S. state-born” is used to refer to Hispanic parents born in the 50 states and the District of Columbia.

c Disorders are not mutually exclusive. An individual might have more than one disorder.

d This included biological, adopted, step, or foster children.

e We conducted a separate analysis that excluded Puerto Rican parents from these analyses, given that Puerto Rico is part of the United States. When excluding Puerto Rican parents, results by place of birth were almost identical to those presented here.

Acknowledgements

This manuscript was prepared using a limited access dataset obtained from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and does not reflect the opinions or views of NIAAA or the U.S. Government.

The authors would like to thank the Steering Committee of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families—along with Melissa Perez, Kristen Harper, Margarita Alegria, Alison Sapp, and Joselyn Angeles-Figueroa—for their helpful comments, edits, and research assistance at multiple stages of this project.

Editor: Brent Franklin

Designer: Catherine Nichols

About the Authors

Both authors contributed equally to this brief.

María A. Ramos-Olazagasti, PhD, is a senior research scientist at Child Trends. Her research explores how social context, exposure to adverse childhood experiences, and culturally relevant risk and protective factors influence the mental health and well-being of Latino youth and families.

Andrew Conway, MSW, is a PhD candidate in the Department of Family Science at the University of Maryland. His research interests focus on the mental health and well-being of Latino immigrant youth and families, particularly as these relate to Latino immigrant youths’ exposure to adverse childhood experiences.

About the Center

The National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families (Center) is a hub of research to help programs and policy better serve low-income Hispanics across three priority areas: poverty reduction and economic self-sufficiency and early care and education. The Center is led by Child Trends, in partnership with Duke University, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, and University of Maryland, College Park. The Center is supported by grant #90PH0028 from the Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation within the Administration for Children and Families in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families is solely responsible for the contents of this brief, which do not necessarily represent the official views of the Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, the Administration for Children and Families, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Copyright 2022 by the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families.

Appendix A

References

1 Cummings, E. M., & Davies, P. T. (1994). Maternal depression and child development. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, 35(1), 73-122.

2 Mojtabai, R., Stuart, E. A., Hwang, I., Eaton, W. W., Sampson, N., & Kessler, R. C. (2017). Long-term effects of mental disorders on marital outcomes in the national comorbidity survey ten-year follow-up. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 52(10), 1217-1226.

3 Mojtabai, R., Stuart, E. A., Hwang, I., Susukida, R., Eaton, W. W., Sampson, N., et al. (2015). Long-term effects of mental disorders on employment in the national comorbidity survey ten-year follow-up. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 50(11), 1657-1668.

4 Van Loon, L. M., Van de Ven, M. O., Van Doesum, K. T., Witteman, C. L., & Hosman, C. M. (2014). The relation between parental mental illness and adolescent mental health: The role of family factors. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23(7), 1201-1214.

5 Mensah, F. K., & Kiernan, K. E. (2010). Parents’ mental health and children’s cognitive and social development. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 45(11), 1023-1035.

6 Pierce, M., Hope, H. F., Kolade, A., Gellatly, J., Osam, C. S., Perchard, R., et al. (2020). Effects of parental mental illness on children’s physical health: systematic review and meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 217(1), 354-363.

7 Goodman, S. H., Rouse, M. H., Connell, A. M., Broth, M. R., Hall, C. M., & Heyward, D. (2011). Maternal depression and child psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14(1), 1-27.

8 Goodman, S. H., & Gotlib, I. H. (1999). Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: a developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychological review, 106(3), 458.

9 Gjerde, L. C., Eilertsen, E. M., Hannigan, L. J., Eley, T., Røysamb, E., Reichborn-Kjennerud, T., et al. (2021). Associations between maternal depressive symptoms and risk for offspring early-life psychopathology: the role of genetic and non-genetic mechanisms. Psychological medicine, 51(3), 441-449.

10 Silberg, J. L., Maes, H., & Eaves, L. J. (2010). Genetic and environmental influences on the transmission of parental depression to children’s depression and conduct disturbance: an extended Children of Twins study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51(6), 734-744.

11 Hettema, J. M., Neale, M. C., & Kendler, K. S. (2001). A review and meta-analysis of the genetic epidemiology of anxiety disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158(10), 1568-1578.

12 American Psychiatric Association. (2018). What Is Mental Illness? American Psychiatric Association. https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/what-is-mental-illness

13 Cook, B. L., Hou, S. S.-Y., Lee-Tauler, S. Y., Progovac, A. M., Samson, F., & Sanchez, M. J. (2019). A review of mental health and mental health care disparities research: 2011-2014. Medical Care Research and Review, 76(6), 683-710.

14 Derr, A. S. (2016). Mental health service use among immigrants in the United States: A systematic review. Psychiatric Services, 67(3), 265-274.

15 Green, J. G., McLaughlin, K. A., Fillbrunn, M., Fukuda, M., Jackson, J. S., Kessler, R. C., et al. (2020). Barriers to mental health service use and predictors of treatment drop out: Racial/ethnic variation in a population-based study. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 1-11.

16 Hamp, A., Stamm, K., Lin, L., & Christidis, P. (2016). 2015 APA Survey of Psychology Health Service Providers: (512852016-001) [Data set]. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/e512852016-001

17 Taylor, P., Lopez, M. H., Martinez, J., Velasco, G. (2012). Language Use among Latinos. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2012/04/04/iv-language-use-among-latinos/#:~:text=Finally%2C%20bilingual%20respondents%20are%20those,24%25%2C%20are%20English%20dominant

18 Brach, C., & Fraserirector, I. (2000). Can Cultural Competency Reduce Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities? A Review and Conceptual Model. Medical Care Research and Review, 57(1_suppl), 181–217. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558700057001S09

19 Handtke, O., Schilgen, B., & Mösko, M. (2019). Culturally competent healthcare – A scoping review of strategies implemented in healthcare organizations and a model of culturally competent healthcare provision. PLOS ONE, 14(7), e0219971. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0219971

29 Betancourt, J. R., Green, A. R., Carrillo, J. E., & Ananeh-Firempong, O. (2003). Defining cultural competence: A practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care. Public Health Reports, 118(4), 293–302.

21 Rathod, S., Gega, L., Degnan, A., Pikard, J., Khan, T., Husain, N., Munshi, T., & Naeem, F. (2018). The current status of culturally adapted mental health interventions: A practice-focused review of meta-analyses. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 14, 165–178. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S138430

22 Guarnaccia, P. J., Martínez Pincay, I., Alegría, M., Shrout, P. E., Lewis-Fernández, R., & Canino, G. J. (2007). Assessing diversity among Latinos: Results from the NLAAS. Hispanic journal of behavioral sciences, 29(4), 510-534.

23 National Hispanic and Latino Mental Health Technology Transfer Center. (2022). ¿Quiénes somos y de dónde venimos? A Historical Context to Inform Mental Health Services with Latinx Populations. Universidad Central del Caribe, Bayamon, PR. https://mhttcnetwork.org/centers/national-hispanic-and-latino-mhttc/product/book-quienes-somos-y-de-donde-venimos-historical

24 Perreira, K. M., Gotman, N., Isasi, C. R., Arguelles, W., Castañeda, S. F., Daviglus, M. L., et al. (2015). Mental health and exposure to the United States: Key correlates from the Hispanic Community Health Study of Latinos. The Journal of nervous and mental disease, 203(9), 670.

25 Alegría, M., Álvarez, K., & DiMarzio, K. (2017). Immigration and mental health. Current epidemiology reports, 4(2), 145-155.

26 Keyes, K. M., Martins, S., Hatzenbuehler, M. L., Blanco, C., Bates, L., & Hasin, D. S. (2012). Mental health service utilization for psychiatric disorders among Latinos living in the United States: the role of ethnic subgroup, ethnic identity, and language/social preferences. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology, 47(3), 383-394.

27 Alegría, M., Canino, G., Shrout, P. E., Woo, M., Duan, N., Vila, D., et al. (2008). Prevalence of mental illness in immigrant and non-immigrant U.S. Latino groups. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165(3), 359-369.

28 Grant, B. F., Chu, A., Sigman , R., Amsbary, M., Kali, J., Sugawara, Y., Jiao, R., Ren, W., & Goldstein , R. (2015). (rep.). National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III (NESARC- III): Source and accuracy statement. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/sites/default/files/NESARC_Final_Report_FINAL_1_8_15.pdf.

29 Grant, B., Goldstein, R., Chou, S., Saha, T., Ruan, W., Huang, B., et al. (2011). The alcohol use disorder and associated disabilities interview schedule-diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, version (AUDADIS-5). Rockville, MD: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism

30 Copeland, W. E., Shanahan, L., Costello, E. J., & Angold, A. (2009). Childhood and adolescent psychiatric disorders as predictors of young adult disorders. Archives of general psychiatry, 66(7), 764-772.

31 Lahey, B. B., Zald, D. H., Hakes, J. K., Krueger, R. F., & Rathouz, P. J. (2014). Patterns of heterotypic continuity associated with the cross-sectional correlational structure of prevalent mental disorders in adults. JAMA psychiatry, 71(9), 989-996.

32 Bureau of the Census. American Community Survey, 2012. Bureau of the Census; Suitland, MD: 2013.

33 National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (n.d.). National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions -III (NESARC-III), Data Notes. https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/sites/default/files/NESARC-III%20Data%20Notesfinal_12_1_14.pdf

34 American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, Fifth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

35 Noe-Bustamante, L. (2019). Key facts about U.S. Hispanics and their diverse heritage. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/09/16/key-facts-about-u-s-hispanics/

36 Duany, J. (2007). Nation and Migration: Rethinking Puerto Rican Identity in a Transnational Context. In: Negrón-Muntaner, F. (Ed.) None of the Above: Puerto Ricans in the Global Era. (pp. 51-64) New Directions in Latino American Cultures. Palgrave Macmillan, New York. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230604360_5

37 Rosario, C. C. & Dillon, F. (2020). Ni de aquí, ni de allá: Puerto Rican acculturation- Acculturative stress profiles and depression. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 26(1), 42-53. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000272

38 Moffitt, T. E., Caspi, A., Taylor, A., Kokaua, J., Milne, B. J., Polanczyk, G., & Poulton, R. (2009). How common are common mental disorders? evidence that lifetime prevalence rates are doubled by prospective versus retrospective ascertainment. Psychological Medicine, 40(6), 899–909. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291709991036

39 Carter, R. T. (2007) Racism and psychological and emotional injury: Recognizing and assessing race-based traumatic stress. The Counseling Psychologist 35(13). http://tcp.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/35/1/13

40 Sacks, V., & Murphey, D. (2018). The prevalence of adverse childhood experiences, nationally, by state, and by race/ethnicity. Child Trends. Retrieved from https://www.childtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/ACESBriefUpdatedFinal_ChildTrends_February2018.pdf

41 Perreira, K. M., & Pedroza, J. M. (2019). Policies of exclusion: Implications for the health of immigrants and their children. Annual Review of Public Health, 40(1), 147–166. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-044115

42 Benuto, L. T., Gonzalez, F., Reinosa-Segovia, F., & Duckworth, M. (2019). Mental health literacy, stigma, and Behavioral Health Service use: The case of Latinx and Non-Latinx whites. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 6(6), 1122–1130. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-019-00614-8

43 Wyse, R., Hwang, W. T., Ahmed, A. A., Richards, E., Deville, C. Jr. Diversity by Race, Ethnicity, and Sex within the US Psychiatry Physician Workforce. Acad Psychiatry,44(5):523-530. doi: 10.1007/s40596-020-01276-z.

44 Weaver, A., & Lapidos, A. (2018). Mental Health Interventions with Community Health Workers in the United States: A Systematic Review. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 29(1), 159–180. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2018.0011

45 Mette, E., Townley, C., & Purington, K. (2019). 50-State Scan: How Medicaid Agencies Leverage their Non-Licensed Substance Use Disorder Workforce – The National Academy for State Health Policy (p. 29). National Academy for State Health Policy. https://www.nashp.org/50-state-scan-how-medicaid-agencies-leverage-their-non-licensed-substance-use-disorder-workforce

46 Miller, B., & Burgos, A. (2021). Enhancing the capacity of the mental health and addiction workforce: A framework. Think Bigger Do Good. https://thinkbiggerdogood.org/enhancing-the-capacity-of-the-mental-health-and-addiction-workforce-a-framework

47 Caplan, S., & Codero, C. (2015). Development of a Faith-Based Mental Health Literacy Program to Improve Treatment Engagement Among Caribbean Latinos in the Northeastern United States of America. Community Health Equity Research & Policy, 35(3), 199–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272684X15581347

48 Repp, A. I., Watson, A. C., Burns, J., & Jones, L. R. (2019). The west side community outreach pilot project: A mental health outreach initiative in urban communities of color. Social Work in Mental Health, 17(6), 662-681. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332985.2019.1625477

49 Pérez-Flores, N. J., & Cabassa, L. J. (2021). Effectiveness of mental health literacy and stigma interventions for Latino/a adults in the United States: A systematic review. Stigma and Health, 6(4), 430–439. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/sah0000343

50 Collins, R. L., Wong, E. C., Breslau, J., Burnam, M. A., Cefalu, M., & Roth, E. (2019). Social marketing of Mental Health Treatment: California’s mental illness stigma reduction campaign. American Journal of Public Health, 109(S3). https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2019.305129

51 American Psychiatric Association. (n.d.) Integrated Care. American Psychiatric Association. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/professional-interests/integrated-care

52 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2021). Telehealth for the Treatment of Serious Mental Illness and Substance Use Disorders. SAMHSA Publication No. PEP21-06-02-001 Rockville, MD: National Mental Health and Substance Use Policy Laboratory. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2021. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/SAMHSA_Digital_Download/PEP21-06-02-001.pdf

53 Working with parents and caregivers (n.d.) Child Welfare Information Gateway. https://www.childwelfare.gov/topics/supporting/mhsu/familymh/parentmh/

54 National Center for Children in Poverty. (2021). Infant and early childhood mental health in home visiting. National Center for Children in Poverty. https://www.nccp.org/mental-health-in-home-visiting/

55 Ramos-Olazagasti, M. A., Scott, M. E., Blechman, J., & Logan, D. (2021). An Introduction to Program Design and Implementation Characteristics of Federally Funded Healthy Marriage and Relationship Education Grantees. Bethesda, MD. https://mastresearchcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/MAST-HMRE-Factsheet_January-2021.pdf

56 National Center on Early Childhood Health and Wellness. (n.d.). Facilitating a Referral for Mental Health Services for Children and Their Families Within Early Head Start and Head Start (EHS/HS). https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/facilitating-referral-mental-health.pdf

57 Betancourt, J. R., Green, A. R., Carrillo, J. E., & Ananeh-Firempong, O. (2003). Defining cultural competence: A practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care. Public Health Reports, 118(4), 293–302.

58 Meléndez Guevara, A. M., Lindstrom Johnson, S., Elam, K., Hilley, C., Mcintire, C., & Morris, K. (2021). Culturally responsive trauma-informed services: A multilevel perspective from practitioners serving Latinx children and families. Community Mental Health Journal, 57(2), 325–339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-020-00651-2

59 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. (2014). (rep.). Improving cultural competence: TIP 59. Rockville, MD. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/sma14-4849.pdf

60 Fortuna, M. (n.d.) Working with Latino/a and Hispanic Patients. American Psychiatric Association. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/cultural-competency/education/best-practice-highlights/working-with-latino-patients

61 Tyson, D. M., Arriola, N. B., & Corvin, J. (2016). Perceptions of Depression and Access to Mental Health Care Among Latino Immigrants: Looking Beyond One Size Fits All. Qualitative Health Research, 26(9), 1289–1302. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1049732315588499

62 Cooper, D. K., Bámaca-Colbert, M., Layland, E. K., Simpson, E. G., & Bayly, B. L. (2021). Puerto Ricans and Mexican immigrants differ in their psychological responses to patterns of lifetime adversity. PLoS ONE, 16(10). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258324

63 Rathod, S., Gega, L., Degnan, A., Pikard, J., Khan, T., Husain, N., Munshi, T., & Naeem, F. (2018). The current status of culturally adapted mental health interventions: A practice-focused review of meta-analyses. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 14, 165–178. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S138430

64 Feeding America. (n.d.). Food Insecurity in Latino Communities. Feeding America. https://www.feedingamerica.org/hunger-in-america/latino-hunger-facts

65 Gennetian, L., Guzman, L., Ramos-Olazagasti, M., & Wildsmith, E. (2019). An Economic Portrait of Low-Income Hispanic Families: Key Findings from the First Five Years of Studies from the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. Report 2019-03. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic & Families. https://hispanicrescen.wpengine.com/research-resources/an-economic-portrait-of-low-income-hispanic-families-key-findings-from-the-first-five-years-of-studies-from-the-national-research-center-on-hispanic-children-families

66 Chen, Y., & Guzman, L. (2021). 4 in 10 Latino and Black Households with Children Lack Confidence That They Can Make Their Next Housing Payment, One Year Into COVID-19. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/4-in-10-latino-and-black-households-with-children-lack-confidence-that-they-can-make-their-next-housing-payment-one-year-into-covid-19/

67 Chen, Y. (2021). During COVID-19, 1 in 5 Latino and Black Households with Children Are Food Insufficient. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/during-covid-19-1-in-5-latino-and-black-households-with-children-are-food-insufficient/

68 Guzman, L., Chen, Y., & Thomson, D. (2020). The Rate of Children Without Health Insurance Is Rising, Particularly Among Latino Children of Immigrant Parents and White Children. Report 2020-05. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://hispanicrescen.wpengine.com/research-resources/the-rate-of-children-without-health-insurance-is-rising-particularly-among-latino-children-of-immigrant-parents-and-white-children

69 Caplan, S. (2007). Latinos, acculturation, and acculturative stress: A dimensional concept analysis. Policy, Politics & Nursing Practice, 8(2), 93–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527154407301751

70 UnidosUS. (n.d.). Key Statistics. UnidosUS. https://www.unidosus.org/facts/statistics-about-latinos-in-the-us-unidosus/

71 Bailey, Z. D., Krieger, N., Agénor, M., Graves, J., Linos, N., & Bassett, M. T. (2017). Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet (London, England), 389(10077), 1453–1463. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X

72 Cai, J. Y., Fremstad, S., & Kalkat, S. (2021). Housing Insecurity by Race and Place During the Pandemic. Center for Economic and Policy Research. https://cepr.net/report/housing-insecurity-by-race-and-place-during-the-pandemic/

73 McKnight-Eily, L. R. (2021). Racial and Ethnic Disparities in the Prevalence of Stress and Worry, Mental Health Conditions, and Increased Substance Use Among Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic—United States, April and May 2020. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 70. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7005a3

74Kessler, R. & Merikangas, K. (2004). The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): background and aims. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 13 (2), 60–68 [PubMed: 15297904]. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/mpr.166

75 Alegría M., Takeuchi, D., Canino, G., Duan, N., Shrout, P., Meng, X. L., Vega, W., Zane, N., Vila, D., Woo, M., Vera, M., Guarnaccia, P., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Sue, S., Escobar, J., Lin, K. M., & Gong, F. (2004). Considering context, place and culture: the National Latino and Asian American Study. International journal of methods in psychiatric research, 13(4), 208–220. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.178

76 Jackson, J. S., Torres, M., Caldwell, C. H., Neighbors, H. W., Nesse, R. M., Taylor, R. J., Trierweiler, S. J., & Williams, D. R. (2004). The National Survey of American Life: A Study of racial, ethnic and cultural influences on mental disorders and Mental Health. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 13(4), 196–207. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.177

77 Swendsen, J., Conway, K. P., Degenhardt, L., Glantz, M., Jin, R., Merikangas, K. R., Sampson, N., & Kessler, R. C. (2010). Mental disorders as risk factors for substance use, abuse and dependence: results from the 10-year follow-up of the National Comorbidity Survey. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 105(6), 1117–1128. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02902.x

78 Alvarez, K., Fillbrunn, M., Green, J. G., Jackson, J. S., Kessler, R. C., McLaughlin, K. A., Sadikova, E., Sampson, N. A., & Alegría, M. (2019). Race/ethnicity, nativity, and lifetime risk of mental disorders in US adults. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 54(5), 553–565. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1644-5

79 Hasin, D. S., Sarvet, A. L., Meyers, J. L., Saha, T. D., Ruan, W. J., Stohl, M., & Grant, B. F. (2018). Epidemiology of Adult DSM-5 Major Depressive Disorder and Its Specifiers in the United States. JAMA psychiatry, 75(4), 336–346. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4602

80 Grant, B. F., Goldstein, R. B., Saha, T. D., Chou, S. P., Jung, J., Zhang, H., Pickering, R. P., Ruan, W. J., Smith, S. M., Huang, B., & Hasin, D. S. (2015). Epidemiology of DSM-5 Alcohol Use Disorder: Results From the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA psychiatry, 72(8), 757–766. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584

81 Grant, B. F., Saha, T. D., Ruan, W. J., Goldstein, R. B., Chou, S. P., Jung, J., Zhang, H., Smith, S. M., Pickering, R. P., Huang, B., & Hasin, D. S. (2016). Epidemiology of DSM-5 Drug Use Disorder: Results From the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III. JAMA psychiatry, 73(1), 39–47. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2132

82 Goldstein, R. B., Smith, S. M., Chou, S. P., Saha, T. D., Jung, J., Zhang, H., Pickering, R. P., Ruan, W. J., Huang, B., & Grant, B. F. (2016). The epidemiology of DSM-5 posttraumatic stress disorder in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III. Social psychiatry and psychiatric epidemiology, 51(8), 1137–1148. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1208-5

83 Kessler, R. C., & Ustün, T. B. (2004). The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). International journal of methods in psychiatric research, 13(2), 93–121. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.168

84 Pai, A., Suris, A. M., & North, C. S. (2017). Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in the DSM-5: Controversy, Change, and Conceptual Considerations. Behavioral sciences (Basel, Switzerland), 7(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs7010007

85 Jensen, P. S., Watanabe, H. K., & Richters, J. E. (1999). Who’s Up First? Testing for Order Effects in Structured Interviews Using a Counterbalanced Experimental Design. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 27(6), 439–445. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1021927909027

Copyright 2025 by the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families.

This website is supported by Grant Number 90PH0032 from the Office of Planning, Research & Evaluation within the Administration for Children and Families, a division of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services totaling $7.84 million with 99 percentage funded by ACF/HHS and 1 percentage funded by non-government sources. Neither the Administration for Children and Families nor any of its components operate, control, are responsible for, or necessarily endorse this website (including, without limitation, its content, technical infrastructure, and policies, and any services or tools provided). The opinions, findings, conclusions, and recommendations expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Administration for Children and Families and the Office of Planning, Research & Evaluation.