The Effects of Monthly Unconditional Cash Support Among Latina Families

Apr 10, 2025

Research Publication

The Effects of Monthly Unconditional Cash Support Among Latina Families

Author

Key Findings From the BFY Study

Overall findings

To provide broader context for findings on how the Baby’s First Years cash gift intervention affected Latina families, we first summarize findings on economic outcomes and family investments on child-specific goods and time for the full sample. BFY families represent a wide variety of ethnic and racial backgrounds and experiences. These background characteristics and experiences—including historical and contemporary economic, political, and social service contexts—affect the ways in which families can and choose to use the BFY cash gift to support their economic well-being and family investments.

Over three years of follow-up, and approximately 36 months of cash gift receipt after childbirth, findings show the following7,8:

- High-cash gift BFY households spent more money on child-specific goods and more time on child-specific early learning activities than the comparison group, low-cash gift households.

- Compared with low-cash gift families, high-cash gift families reported lower rates of public benefit receipt and fewer were residing in poverty, although mean income and wealth remained low for the majority of BFY families by year 3.

- High-cash gift households did not differ from low-cash gift households on spending in other core household expenditures, maternal employment in the formal labor market, or BFY children’s participation in nonparental care.

Key findings among BFY Latina families

Within the context of overall BFY findings, we explored how the BFY cash gift specifically impacted Latina families. At the time of the child’s birth, BFY Latina families look different on some aspects of family life than their BFY study peers: BFY Latina families have higher rates of being married or living with the biological father of the BFY-enrolled child and lower rates of benefit receipt for some government programs despite being eligible based on income. These characteristics differ from non-Latina BFY families in ways that look similar to comparisons of Latino families to their peers in nationally representative samples.9 These characteristics related to family structure and receipt of other government benefits help contextualize how the BFY cash gift might be used and experienced among Latina families.

Over three years of follow-up, and approximately 36 months of cash gift receipt after childbirth, findings among BFY Latina families show the following10:

- High-cash gift Latina households had higher net income and higher income-to-needs ratios than BFY Latina low-cash gift households, in magnitudes similar to findings for the full sample of BFY households. This is notable, as the cash gift had similar impacts on household income despite differences in Latina households (versus peer BFY households) on background characteristics related to family structure and government benefit receipt.

- High-cash gift Latina households spent more money on child-specific goods in the prior month—including diapers, books, toys, and clothes—relative to low-cash gift Latina households.

- High-cash gift Latina mothers reported similar engagement in child-specific early learning activities—such as reading books, telling stories, and playing with the BFY-enrolled child—relative to low-cash gift Latina mothers.

BFY Latina households in the high- and low-cash gift groups showed similar amounts of spending on other core expenditures, with the exception of higher spending on food eaten out among high-cash versus low-cash gift Latino households. Collectively, these findings offer insights into how Latino families invest in response to increased family income resulting from monthly unconditional cash support.

Background

U.S. Latino families represent a wide variety of circumstances and experiences. As previously mentioned, while rates of child poverty are high among Latino children, Latino families with low incomes also have several characteristics associated with economic security and support of children’s positive development. Latino households with children have high rates of adult employment and stable earnings, both predictors of economic security.11,12 Many Latino children in families with low incomes reside with both parents, another favorable predictor of resources available to support children.11 On the other hand, half of Latino parents have jobs with irregular work schedules, which can be challenging to juggle with family life.13 One quarter of Latino children with low incomes reside in households with an undocumented adult.14 In addition, low literacy (in any language) and English language proficiency among Latino parents may interfere with employment opportunities15; at the same time, however, bi- and multilingualism for children are favorably associated with their future outcomes.16

These dimensions—related to citizenship status, residing with multiple adults, and language and literacy proficiency—also intersect with families’ experiences with government programs. Families with one or more employed parents, mixed nativity or citizenship status, and limited English proficiency often face obstacles satisfying earnings and citizenship documentation requirements for government benefit receipt, inhibiting their utilization of government services and assistance.17 Stigma around public benefit receipt can further dissuade Latino families with children from taking up government benefits.18,19 Indeed, receipt rates of several government benefit programs are lower among eligible Latinos than among their eligible peers, especially for households with Latino children with a non-U.S.-born parent.20, 21 For instance, recent estimates from the 2021 expanded Child Tax Credit show that Latino children in households with low incomes were the least likely to receive the tax credit.22

Looking at Latina families in the Baby’s First Years study makes two contributions to the broader literature on poverty reduction interventions and the impact of unconditional cash. First, very few guaranteed income and related unconditional cash transfer studies in the United States, to date, have included a large sample of Latino families with children, let alone young children.c This research also contributes more broadly to questions about the role of cash support that can also inform other types of safety net programs. Second, the delivery format and mechanism of the BFY study cash gift has very low administrative burden and low stigma: It is automatically activated and disbursed monthly starting at the time of the child’s birth, does not require proof of citizenship (e.g., a Social Security number), and is guaranteed through six years with no recertification or adjustment in amount based on changing family circumstances. Thus, it avoids difficulties in satisfying documentation requirements and stigma around benefit receipt that might interfere with Latino families accessing government benefits or other types of income support.

A regular monthly cash transfer, such as the one examined here, is hypothesized to increase family investments in children’s home environments. Families may use the cash support gift to increase the amount and quality of goods available (e.g., books, toys, and children’s learning environments) or to spend more time with children, with potential reductions in work hours. These types of monetary and time investments have been demonstrated to support children’s development, particularly in the context of low incomes.5 However, it is an open question whether monetary and time investments differ for Latino families with low incomes. Established literatures on similar questions about family investments in time and money have conventionally drawn on data from studies and programs that are limited in their ability to speak to Latino children and their wide variety of contemporary and historical experiences in the United States.23

Methods

One thousand mothers with low incomes and their newborn babies were recruited from four sites: the greater Omaha, Nebraska area; New Orleans, Louisiana; New York City; and the Twin Cities, Minnesota. The sample was 41 percent Latina, 40 percent Black, 11 percent non-Hispanic White, and 9 percent non-Hispanic other. The ethnic and racial composition of the BFY families was not equally distributed across sites: The BFY Latina sample is 83 percent (n=240) in New York City, 36 percent (n=106) in Greater Omaha, 23 percent (n-28) in the Twin Cities, and 11 percent in New Orleans (n=32).

Findings are presented from two types of analyses. First, we show descriptive patterns of BFY spending among Latina mothers (N=392) from transactions on the 4MyBaby debit card coded into merchant categories (i.e., Figure 1). Information on each point-of-sale transaction from the 4MyBaby debit card is collected among mothers who consented to using their transaction data (n=900 overall; n=363 Latina). This information includes merchant name, the state in which the merchant is located, date of purchase, transaction status (e.g., approved/denied), and transaction amount. The names of merchants were cleaned and coded into 90 different merchant categories (e.g., grocery store/supermarket, restaurant) based on Visa Merchant Category Classification (MCC) codes.

Second, this brief presents intent-to-treat (ITT) estimates of the impact of the high-cash gift on economic outcomes and family investments on child-specific goods and time, using data from the first three years of cash gift receipt.d Data were collected in three annual survey waves, corresponding to child ages 1, 2, and 3.e ITT estimates are presented pooling (or stacking) the three waves of survey data to estimate a treatment effect across children’s first three years of life (“pooled estimates”). ITT estimates and 95 percent confidence intervals are indicated in Figure 2. Because the majority of mothers in BFY identify as Latina (41%) or non-Hispanic Black (40%), statistical tests of differences in impacts between groups are most clearly represented as a test of comparisons between Latina and Black BFY families. Thus, statements made regarding impacts among BFY Latina families are informed by chi-squared tests of equivalence of pooled ITT-impact estimates between the BFY Latina families and BFY Black families. The findings from these equivalence tests show differences in the size of impacts on the BFY parent-child activities index (p = 0.03) and expenditures on food eaten out (p = 0.02), and for the BFY focal child specific goods expenditure index (p = 0.06). Values of p<0.05 for a particular outcome indicate that the impact of the BFY cash gift among BFY Latina families statistically differs from the impact among BFY Black families, with values of p<0.10 at the margins of statistical significance. Statistical differences between BFY high-cash gift impacts among Latina families and Black families were not detected for other outcomes examined in this brief.

Baseline characteristics of BFY Latina families in the high-cash and low-cash gift groups do not statistically differ (as indicated by a joint test of orthogonality). Nevertheless, ITT estimates are adjusted for baseline characteristics as pre-registered (mother’s age, completed schooling, household income, net worth, general health, mental health, race and ethnicity, marital status, number of adults in the household, number of other children born to the mother, smoked during pregnancy, drank alcohol during pregnancy, father living with the mother, child’s sex, birth weight, and gestational age at birth). Other covariates included phone interview and child age at interview (in months above target age). As described in the BFY study pre-registered analysis plans, the BFY study was not designed to detect statistical differences across subpopulations but, rather, was powered to detect differences for the full sample of n=1,000 initially enrolled with reasonable assumptions about attrition and useable data over time. Site-based differences are not influencing the findings shown here among BFY Latina families to the extent that it is statistically feasible to differentiate impacts among BFY Latina families from New York City site-specific impacts.

The household income, child expenditure, and parent-child activities outcomes examined in this brief are described in more detail in Gennetian et al. (2024).7

Results

Sample characteristics

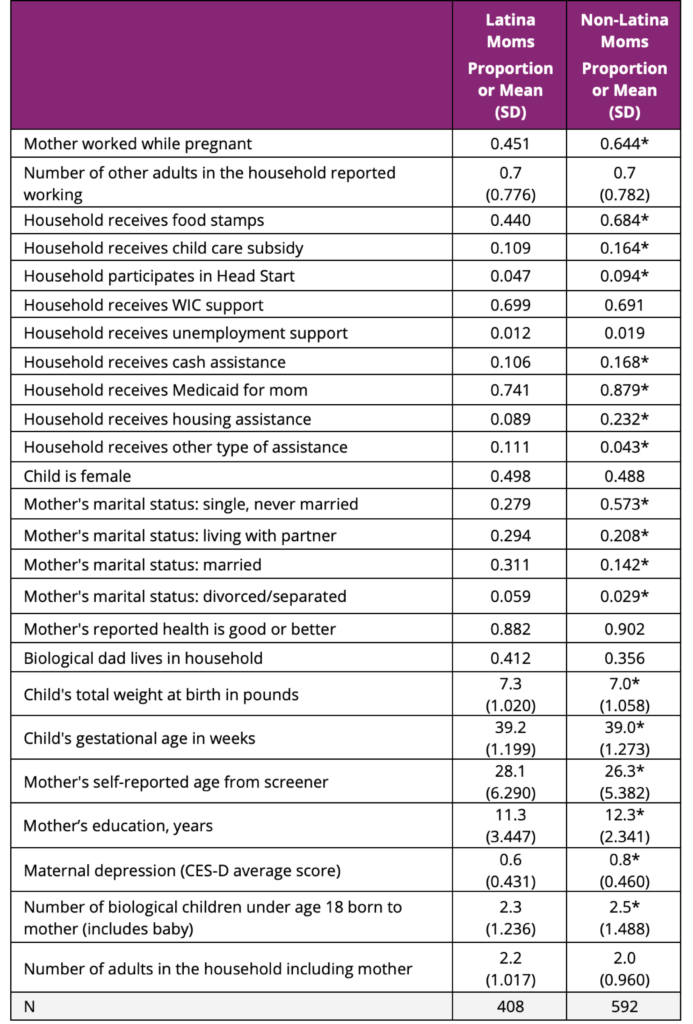

At the time of study enrollment, mothers in BFY Latina families were more likely than in non-Latino BFY families to be married or residing with the biological father of the BFY child, and less likely to receive some types of government program benefits (Table 1). These differences among families in BFY between Latinos and other racial and ethnic groups are similar to those found when comparing Latinos to peers in nationally representative samples.24

Based on maternal reports, 42 percent of BFY Latina families are Dominican, with the remainder being Mexican (26%), Puerto Rican (7%), Honduran (6%), a combination (7%), or other (13%). One third of the BFY Latina mothers (31%) were born in the United States.

Transactions with the BFY cash gift money among Latina families

Nearly all Latina families in the BFY high-cash gift group used the 4MyBaby debit card at least once, with most making at least one transaction every month, including cash withdrawals at ATMs, stores, and point-of-sale purchases. Figure 1 depicts the distribution of transactions across top point-of-sale vendors and types of vendor, along with withdrawals from ATMs, across the three-years (or 36 months) of high-cash gift receipt. The top five vendors or categories for point-of sale transactions were grocery store/supermarket (11%), Walmart (9%), phone (3%), wholesale (3%), and online variety store (3%), largely similar to the top five categories for other BFY families.

Figure 1. Latina families used the BFY high-cash gift money at a variety of vendors including grocery stores, Walmart, and online variety stores.

Point-of-scale transactions with BFY high-cash gift money, on average, over 36 months of cash gift receipt, BFY Latina families, 2018-2021

Source: Baby’s First Year’s study data from 4MyBaby debit card transactions.

Impacts on income and expenditures

BFY Latina high-cash gift families had higher net incomes and lower poverty than BFY Latina low-cash gift families, in magnitudes similar to findings for the full sample of BFY families.

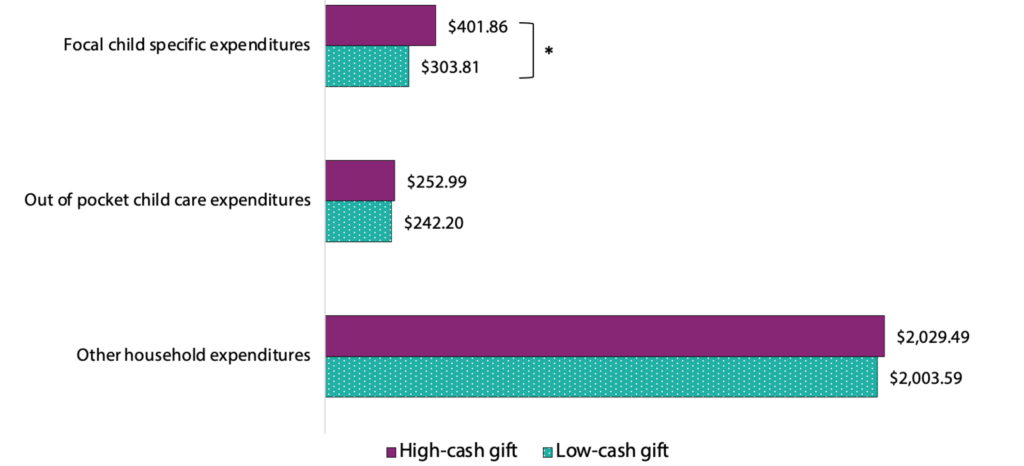

Latina high-cash gift families reported higher spending on child-specific goods (an impact estimate of approximately $100, on average, in the prior month) than low-cash gift families (Figure 2). Looking broadly at different types of categories of goods and expenditures measured in the survey, most other core expenditures—food at home, utilities, cable, rent, child care, and remittances (money sent to others)—were similar for Latina high- and low-cash gift families. There were no impacts of the BFY high-cash gift on household spending on cigarettes and alcohol among BFY Latina families. BFY high-cash gift Latina families reported being more likely to spend money eating out and reported higher expenditures on food eaten out ($59/month), relative to low-cash gift families. This pattern of findings was similar to findings for the overall sample of BFY families.

Figure 2. Latina high-cash gift families reported higher spending on child-specific goods compared to low-cash gift families.

Impact estimates of BFY high-cash gift on child-specific and household expenditures, estimates pooled across three years of follow-up, BFY Latina families, 2018-2021

Notes: *Difference is statistically significant at p<.05.Child-expenditures is the total money spent on books, toys, diapers, clothing, activities and electronic programs and media for the focal child as reported by the mother in the month prior to the survey. Out-of-pocket child care is money spent out-of-pocket on all of focal child’s child care arrangements in the week prior to the survey. Other household expenditures include money spent on utilities, cable, internet, phone or cell including data charges, food eaten at home, food eaten out, rent, remittances, alcohol, and cigarettes. Each of these are adjusted to reflect spending in the prior or in a typical month and then summed.

ITT estimates are adjusted by covariates from the baseline survey: mother’s age, completed schooling, household income, net worth, general health, mental health, race and ethnicity, marital status, number of adults in the household, number of other children born to the mother, smoked during pregnancy, drank alcohol during pregnancy, father living with mother, child’s sex, birth weight, gestational age at birth. Other covariates: phone interview, child age at interview (in months above target age). Missing covariate values are imputed using the full sample mean among the sample of respondents who completed the baseline survey. Missing covariate dummies are included in covariate-adjusted models.

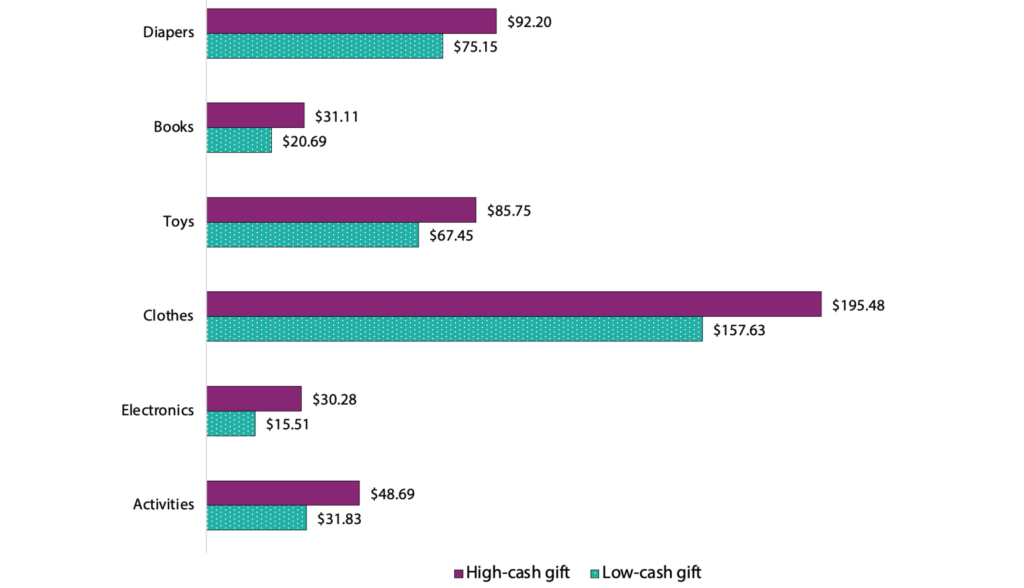

Figure 3 shows the impact estimates of the BFY high-cash gift on child-specific expenditures, by type of expenditure. Latina high-cash gift families reported $17 of increased spending on diapers $10 on books, $18 on toys, and $39 on clothes.

Figure 3. Latina high-cash gift families reported higher spending across six types of child-specific expenditures compared to low-cash gift families.*

Impact estimates of the BFY high-cash gift on child-specific expenditures, by type, for BFY children in Latina families, pooled across three years of follow-up, 2018-2021

Source: Baby’s First Year’s study data.

Notes: *Difference is statistically significant at p<.05 for all six types of child-specific expenditures.

Each of these child-expenditure items are the total of money spent on ITEM for the focal child in the month prior to the survey as reported by the mother. Spending on diapers is only asked in the first follow-up survey when the focal child is age 1. Spending on activities is only asked in the second and third follow-up surveys when the focal child is age 2 and 3.

ITT estimates are adjusted by covariates from the baseline survey: mother’s age, completed schooling, household income, net worth, general health, mental health, race and ethnicity, marital status, number of adults in the household, number of other children born to the mother, smoked during pregnancy, drank alcohol during pregnancy, father living with mother, child’s sex, birth weight, gestational age at birth. Other covariates: phone interview, child age at interview (in months above target age). Missing covariate values are imputed using the full sample mean among the sample of respondents who completed the baseline survey. Missing covariate dummies are included in covariate-adjusted models.

Impacts on mothers’ engagement in early learning activities

With respect to maternal engagement with the BFY-enrolled child, BFY Latina high-cash gift mothers reported relatively similar frequency of engagement in early enriching activities as Latina low-cash gift mothers.

Discussion

The Baby’s First Years study offers an unprecedented opportunity to look at how cash transfers, delivered through private or charitable sources, affect spending and other aspects of family life among Latina families with low incomes and young children. The impacts of the BFY high-cash gift on household income were qualitatively similar to the overall BFY findings. In other words, the high-cash gift had similar impacts for Latina families despite differences in background characteristics associated with Latino ethnicity such as family structure. This may suggest that unconditional cash transfers generate qualitatively similar behavioral responses, including adjustments in earnings or other sources of income, irrespective of Latino ethnicity within families with low incomes.

This brief describes three findings among BFY Latina families that differ from previously published findings for the full sample of BFY families. The first is related to money spent on child-specific goods: Impacts of the high-cash gift on these goods were much higher among BFY Latina families than for the overall sample. That is, when provided cash that comes with freedom to decide how to spend it, Latina families disproportionally chose to spend it on child-specific goods like diapers, books, and toys. Second, impacts on money spent on food eaten out were larger among BFY Latina families. This could reflect a number of factors related to time use (e.g., savings in time with food preparation), but it also more broadly speaks toward social, cultural, and community norms and the meaning of the BFY cash gift—for example, to be put toward investments in family gatherings and celebrations. Third, the BFY high-cash gift had no detectable impact on engagement in early learning activities among BFY Latina families.

This third finding differs from previously published findings showing that the high-cash gift increased maternal engagement in early learning activities. In BFY Latina families, other caregivers might play a role in engaging children in early learning activities in light of high-cash gift receipt, whereas engagement with the child primarily occurs via mothers in other BFY families. Unfortunately, information about time spent with children by other caregivers or siblings is not available in the BFY data to further explore this or related factors.

Latino families, as an ethnic group, vary in many ways, including U.S. nativity status and citizenship, country of heritage, and racial identity. Their cultures, experiences, and access to resources also differ along these dimensions. BFY is not statistically powered to explore these differences. Nevertheless, this work furthers our understanding of the variety of ways in which direct cash support impacts Latino families with young children and low incomes.

Table 1. Characteristics at study entry of BFY by Latina ethnicity

Note: Statistically significant differences according to a 2-sided t-test with p<0.05 are indicated with *

Footnotes

aThis brief will use the term “Latina” to describe Hispanic and Latina mothers, recognizing that “Hispanic” and “Latino/a,” can be—and often are—used interchangeably, and that not all BFY birthing parents may identify as female. Consistent with the Office of Budget and Management’s (OMB) standards for data on race and ethnicity, these terms refer to individuals of Mexican, Puerto Rican, Salvadoran, Cuban, Dominican, Guatemalan, and other Central or South American or Spanish cultures or origins. Our selection of a particular term is motivated by the underlying data, the preference expressed by the individuals or communities being discussed, or the context and specific research questions being addressed.

bPer mothers’ self-reports, 41 percent identify as Latina; 40 percent of BFY mothers as Black; 11 percent as White, non-Hispanic; <1 percent as Asian/Pacific Islander; 1.5 percent as Native American; and 7 percent as belonging to multiple races/other.

cOne notable exception is The Bridge Project in New York City. https://bridgeproject.org/

dAnalyses follow pre-registration analytic protocols on pre-registered secondary outcomes. The study is registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03593356; first posted July 2018, https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03593356) and on the American Economic Association’s registry (AEARCTR-0003262, first posted June 2019, https://www.socialscienceregistry.org/trials/3262).

eThroughout this brief, we use “age” and “wave” interchangeably to refer to years of annual survey data.

Suggested Citation

Gennetian, L. A., Shah, H., Basurto, L. E., Stilwell, L., Yoshikawa, H., Freire, S., Magnuson, K., Duncan, G., Fox, N., Halpern-Meekin, S. (2025). The effects of monthly unconditional cash support among Latina families. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. DOI: 10.59377/590p8000g

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Steering Committee of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families—along with Krista Perreira, Phil Fisher, Nicole Constance, Kristen Harper, Laura Ramirez, and Ana Maria Pavić—for their helpful comments, edits, and research assistance at multiple stages of drafting this brief. The Center’s Steering Committee is made up of the Center investigators—Drs. Natasha Cabrera (University of Maryland, Co-PI), Danielle Crosby (University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Co-PI), Lisa Gennetian (Duke University; Co-PI), Lina Guzman (Child Trends, Director and PI), Julie Mendez (University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Co-PI), and María Ramos-Olazagasti (Child Trends, Deputy Director and Co-PI)—and federal project officers Drs. Ann Rivera, Jenessa Malin, and Kimberly Clum (Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation), and Dr. Shirley Huang (Society for Research in Child Development Policy Fellow, Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation).

Editor: Brent Franklin

Designers: Catherine Nichols & Joseph Boven

About the Authors

Lisa A. Gennetian, PhD, is a co-Principal Investigator of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, leading the research area on poverty and economic self-sufficiency. She is the Pritzker Professor of Early Learning Policy Studies at Duke University Sanford School of Public Policy and co-PI of the Baby’s First Years Study.

Hema Shah, graduate student, PhD Economics, Duke University.

Luis E. Basurto, graduate student PhD Public Policy, Brook School of Public Policy, Cornell University.

Laura Stilwell, PhD, MD in process, Duke University.

Hirokazu Yoshikawa, PhD, Professor of Globalization and Education, New York University Steinhardt and co-PI of the Baby’s First Years Study.

Silvana Freire, graduate student, PhD in Psychology and Social Intervention, New York University.

Katherine Magnuson, PhD, Professor and Director of the Institute for Research on Poverty, University of Wisconsin-Madison and co-PI of the Baby’s First Years Study.

Kimberly G. Noble, PhD, MD, Professor of Neuroscience and Education, Columbia University and co-PI of the Baby’s First Years Study.

Greg Duncan, PhD, Distinguished Professor of Education, University of California, Irvine and co-PI of the Baby’s First Years Study.

Nathan Fox, PhD, Distinguished Professor of Education, University of Maryland and co-PI of the Baby’s First Years Study.

Sarah Halpern-Meekin, PhD, Professor of Human Development & Family Studies, University of Wisconsin-Madison and lead PI of the Baby’s First Years qualitative study, Mothers Voices.

About the Center

The National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families (Center) is a hub of research to help programs and policy better serve low-income Hispanics across three priority areas: poverty reduction and economic self-sufficiency, healthy marriage and responsible fatherhood, and early care and education. The Center is led by Child Trends, in partnership with Duke University, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, and University of Maryland, College Park. This publication was supported by the Administration for Children and Families (ACF) of the United States (U.S.) Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of two financial assistance awards (Award # 90PH0028, from 2018-2023, and Award # 90PH0032 from 2023-2028) totaling $13.5 million across the two awards with 99 percentage funded by ACF/HHS and 1 percentage funded by non-government sources.

The contents are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement, by ACF/HHS, or the U.S. Government. For more information, please visit the ACF website, Administrative and National Policy Requirements.

Copyright 2025 National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families

References

1National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Consequences of child poverty. In A roadmap to reducing child poverty, 67–96 (Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2019).

2National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2024). Reducing Intergenerational Poverty. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/27058/reducing-intergenerational-poverty

3Shrider, E. A. (2024). Poverty in the United States: 2023. Current Population Reports. United States Census Bureau. https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/2024/demo/p60-283.pdf

4Lee, J. Acevedo-Garcia, D., Collyer, S., Joshi, P., Kaushal, N., Walters, A. N., Wimer, C. (2024). The role of government transfers in the child poverty gap by race and ethnicity: A focus on Black, Latino, and White children. Center on Poverty & Social Policy; Institute for Child, Youth, and Family Policy. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/610831a16c95260dbd68934a/t/66204441538b352a9a590dab/1713390657952/Child-poverty-gap-Black-Latino-White-CPSP-ICYFP-2024.pdf

5Attanasio, O., Cattan, S., & Meghir, C. (2022). Early Childhood Development, Human Capital, and Poverty. Annual Review of Economics, 14. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-092821-053234

6Gennetian, L. A., Shah, H., Basurto, L. E., Stilwell, L., Yoshikawa, H., Freire, S., Magnuson, K., Duncan, G., Fox, N., Halpern-Meekin, S. (forthcoming). Impacts of unconditional cash transfers on monetary and time investments in young children: Heterogeneity across Black and Latina families with low income in the U.S.

7Gennetian, L. A., Duncan, G. J., Fox, N. A., Halpern-Meekin, S., Magnuson, K., Noble, K. G., Yishikawa, H. (2024). Effects of a monthly unconditional cash transfer starting at birth on family investments among US families with low income. Nature Human Behavior, 8, 1514–1529. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-024-01915-7

8Sauval, M., Duncan, G. J., Gennetian, L. A., Magnuson, K. A., Fox, N. A., Noble, K. G., & Yoshikawa, H. (2024). Unconditional cash transfers and maternal employment: Evidence from the Baby’s First Years Study. Journal of Public Economics, 236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2024.105159

9Gennetian, L. A. (2024). Highlights from a decade of the Center’s research on supports for economic self-sufficiency among Latino families with children. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. DOI:10.59377/994e1263e

10Shah, H., et al. (forthcoming).

11Turner, K., Guzman, L., Wildsmith, E., & Scott, M. (2015). The Complex and Varied Households of Low-Income Hispanic Children. National Research Center on Hispanic Children and Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/the-complex-and-varied-households-of-low-income-hispanic-children/

12Gennetian, L.A., C. Rodrigues, H.D. Hill, and P.A. Morris (2018). Income level and volatility by children’s race and Hispanic ethnicity. Journal of Marriage and Family, 81(1): 204-29. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12529

13Wildsmith, E., Ramos-Olazagasti, M. A., & Alvira-Hammond, M. (2018). The Job Characteristics of Low-Income Hispanic Parents. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://hispanicrescen.wpengine.com/publications/the-job-characteristics-of-low-income-hispanic-parents/

14Clarke, W., Turner, K., & Guzman, L. (2017). One quarter of Hispanic children in the United States have an unauthorized immigrant parent. National Research Center on Hispanic Children and Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/one-quarter-of-hispanic-children-in-the-united-states-have-an-unauthorized-immigrant-parent/

15Pew Research Center. Bilingualism. https://www.pewresearch.org/race-and-ethnicity/2004/03/19/bilingualism/

16Gándara, P. (2018). The economic value of bilingualism in the United States. Bilingual Research Journal, 41(4), 334-343. https://doi.org/10.1080/15235882.2018.1532469

17 Gennetian L. A., Hill, Z., Ross-Cabrera, D. (2020). State-level TANF policies and practice may shape access and utilization among Hispanic families. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/state-level-tanf-policies-and-practice-may-shape-access-and-utilization-among-hispanic-families/

18Levine, J. (2013). Ain’t no trust: How bosses, boyfriends, and bureaucrats fail low income mothers and why it matters. University of California Press.

19Haley, J., Kenney, G., Bernstein, H., & Gonzalez, D. (2020). One in five adults reported chilling effects on public benefit receipt in 2019. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/one-five-adults-immigrant-families-children-reported-chilling-effects-public-benefit-receipt-2019

20Bitler, M., Gennetian, L. A., Gibson-Davis, C., & Rangel, M. (2021). Means-Tested Safety Net Programs and Hispanic Families: Evidence from Medicaid, SNAP, and WIC. The ANNALS of the Academy of Political and Social Science, 696(1), 274-305. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027162211046591

21Thompson, D., Chen, Y., Gennetian, L. A., & Basurto, L. E. (2022). Earned income tax credit receipt by Hispanic families with children: state outreach and demographic factors. Health Affairs, 41(12).

https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2022.00725

22Karpman, M., Maag, E., Kenney, G. M., & Wissoker, D. A. (2021). Who has received advance Child Tax Credit payments, and how were the payments used? Patterns by race, ethnicity, and household income in the July-September 2021 Household Pulse Survey. Urban Institute. https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/sites/default/files/publication/163132/who-has-received-advance-ctc-payments-and-how-were-the-payments-used_0.pdf

23García, J. L., & Heckman, J. J. (2023). Parenting promotes social mobility within and across generations. Annual Review of Economics, 15, 349-388. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-021423-031905

24Gennetian, L. A., & Tienda, M. (2021). Investing in Latino Children and Youth: Volume Introduction and Overview. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 696(1), 6-17. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027162211049760

Copyright 2025 by the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families.

This website is supported by Grant Number 90PH0032 from the Office of Planning, Research & Evaluation within the Administration for Children and Families, a division of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services totaling $7.84 million with 99 percentage funded by ACF/HHS and 1 percentage funded by non-government sources. Neither the Administration for Children and Families nor any of its components operate, control, are responsible for, or necessarily endorse this website (including, without limitation, its content, technical infrastructure, and policies, and any services or tools provided). The opinions, findings, conclusions, and recommendations expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Administration for Children and Families and the Office of Planning, Research & Evaluation.