Sep 22, 2021

Research Publication

Practitioners in New Mexico’s TANF Program Offer Perspectives on Engaging Hispanic Families

Authors:

Overview

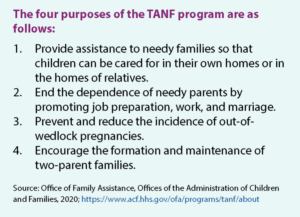

Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) is a federally funded program that provides time-limited cash assistance to help families with children meet their basic needs, along with a wide range of services to help them achieve economic self-sufficiency.1 The TANF program is administered by state and county agencies, with flexibility to decide how funding is allocated and applied as long as allocations meet at least one of TANF’s four overarching goals. This flexibility, in turn, means that the experiences of families who engage with the TANF basic cash assistance program will vary based on the state in which they live. Much of what we know about families’ experiences with social service programs comes from families themselves. However, program practitioners—who administer programs and engage directly with families—also offer a unique and important perspective on the barriers and facilitators that families encounter in applying for and using social services.

This brief draws from a recent survey of TANF program practitioners in New Mexico to describe how state and local TANF agencies engage with Hispanica families who apply for TANF cash assistance.b We highlight responses from administrative staff and frontline practitioners to questions on issues important to Hispanic family engagement, including (1) language access, (2) immigration-related issues, and (3) strategies to improve access and engagement of Hispanic families (e.g., organizational processes, staffing, and training). Based on these responses, we identify key activities that may support positive program engagement with Hispanic families seeking TANF cash assistance. We also summarize recommendations from practitioners who participated in the study, which New Mexico and other states might consider to facilitate effective engagement with Hispanic families.

Survey Design and Methods

The New Mexico practitioner survey used for this brief is part of a broader research project examining how social assistance policies and practices impact utilization and outcomes among Hispanic low-income youth across all states. This survey was designed to examine practitioners’ perceptions about engaging Hispanic families in the TANF program. Questions focused on a range of topics, including the political environment, economic climate and budgetary constraints, program mission and goals, organizational processes, staff attitudes and beliefs, training and staff development, and office design. The survey included questions about organizational practices that facilitate or impede access to benefits among Hispanic families, as well as COVID-19 emergency response measures and benefits offered through the TANF system. No information was collected about the demographic or related characteristics of the practitioners, with the exception of their job title and location of work.

The New Mexico practitioner survey used for this brief is part of a broader research project examining how social assistance policies and practices impact utilization and outcomes among Hispanic low-income youth across all states. This survey was designed to examine practitioners’ perceptions about engaging Hispanic families in the TANF program. Questions focused on a range of topics, including the political environment, economic climate and budgetary constraints, program mission and goals, organizational processes, staff attitudes and beliefs, training and staff development, and office design. The survey included questions about organizational practices that facilitate or impede access to benefits among Hispanic families, as well as COVID-19 emergency response measures and benefits offered through the TANF system. No information was collected about the demographic or related characteristics of the practitioners, with the exception of their job title and location of work.

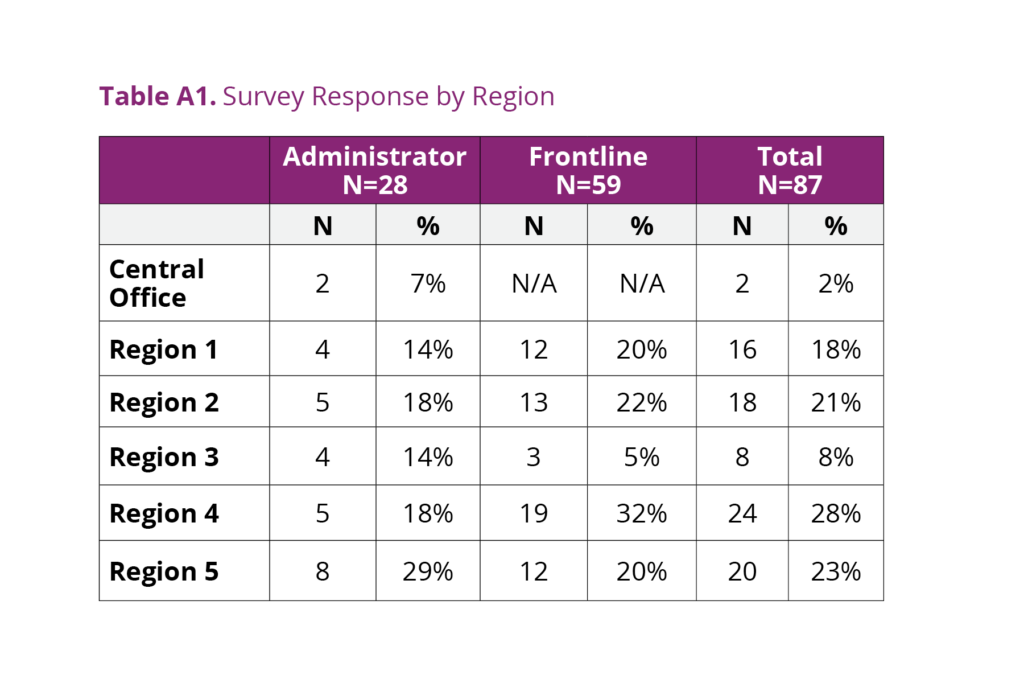

In June 2020, the survey was administered online to frontline TANF program staff, as well as state and county administrators at the NMHSD ISD. The ISD provided researchers with a list of 121 administrative and frontline practitioners (including regional office managers, county directors, family assistance analysts [FAA], TANF liaisons, immigration ambassadors, and creative work solutions career development specialists) across each of New Mexico’s 33 counties and state Central Office (including staff managers and a NM Works contract manager). A total of 87 practitioners from 25 counties responded to the survey, including 28 administrators (76%) and 59 frontline staff (70%) (see Table A1 for response rate by region).

The survey included close-ended question on the topics above, as well as several open-ended questions that allowed practitioners to (1) identify any barriers to Hispanic families in accessing the TANF program and (2) list their recommendations for improving access. We tested for differences in responses to the close-ended questions across various regional and county-level characteristics. No differences in survey responses were identified by county-level poverty, population size, or political party affiliation. Additionally, we tested for differences between frontline staff and administrative staff. There were few statistical differences in responses between these groups, and all are noted in the text.

Questionnaire Findings: Organizational practices linked to access

This section highlights findings from practitioners (both administrators and frontline staff) in response to close-ended questions about which organizational practices they felt facilitated or impeded TANF program access among Hispanic families in their communities. We focus on three themes that the survey questions asked about: language access, immigration-related issues, and strategies to improve access and engagement of Hispanic families (e.g., organizational processes, staffing, and training).f

Language access

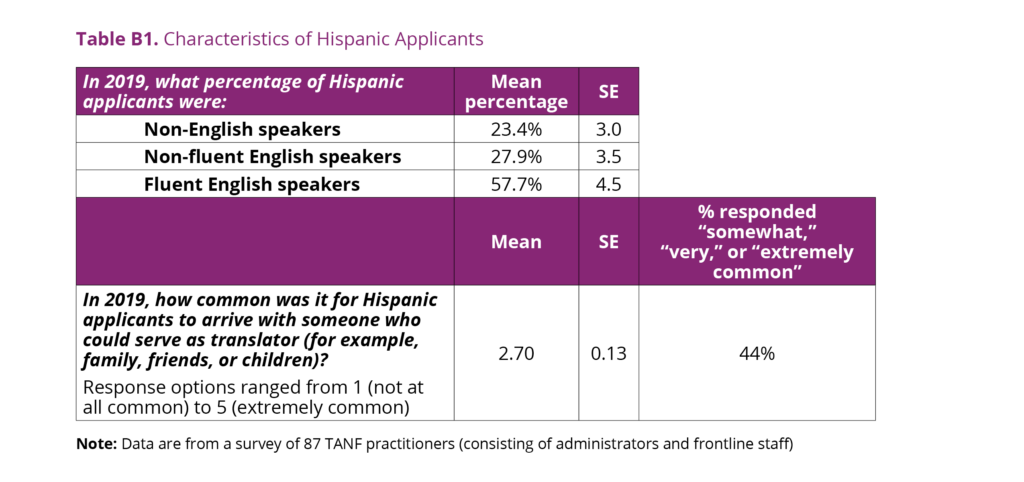

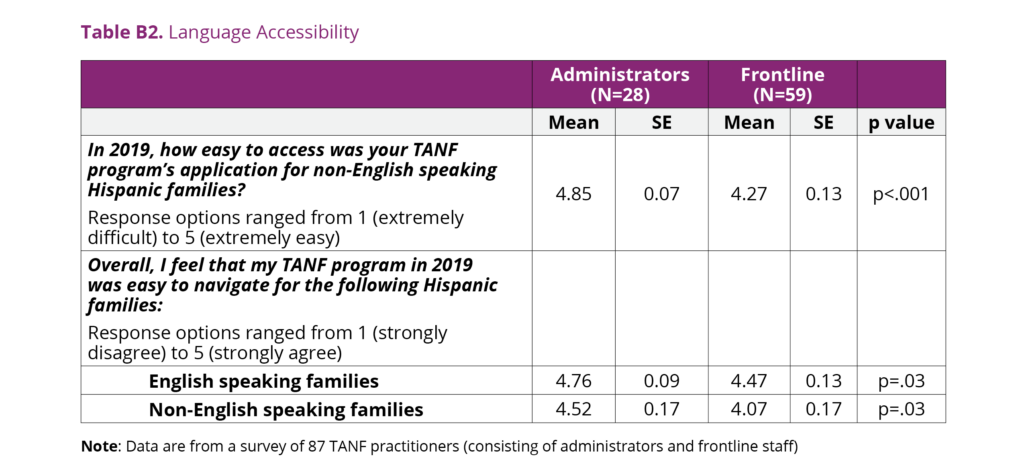

Practitioners reported that accessibility of the TANF program application process varied for applicants by their language status. Specifically, TANF program application was reported to be easier for English-speaking applicants, which is concerning as almost one quarter of Hispanic applicants are believed to not speak any English. In fact, 44 percent of frontline staff reported that Hispanic applicants are somewhat, very, or extremely likely to bring their own interpreters for appointments (see Tables B1 and B2).

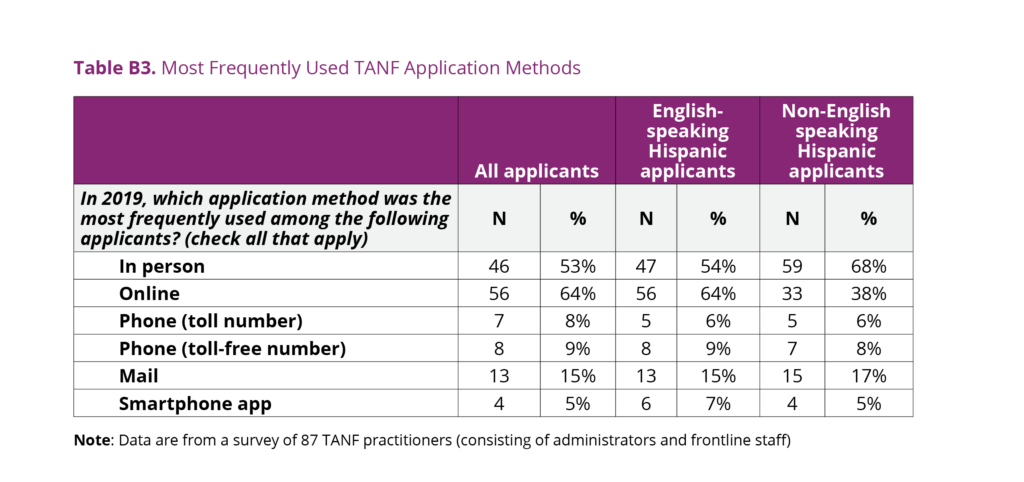

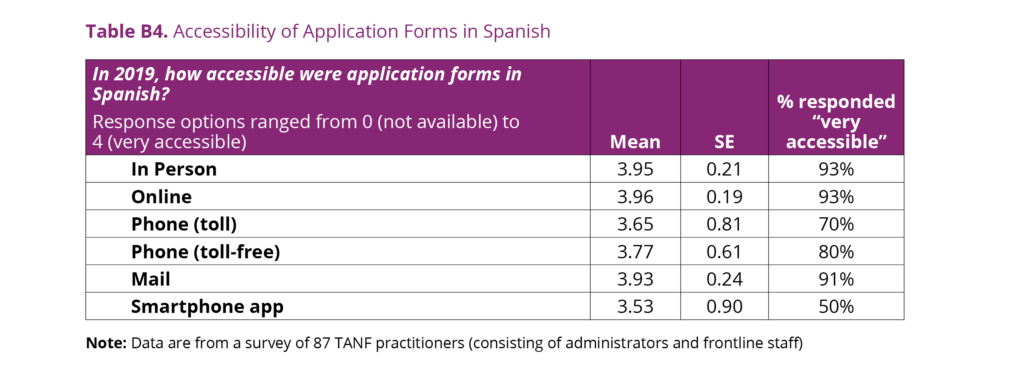

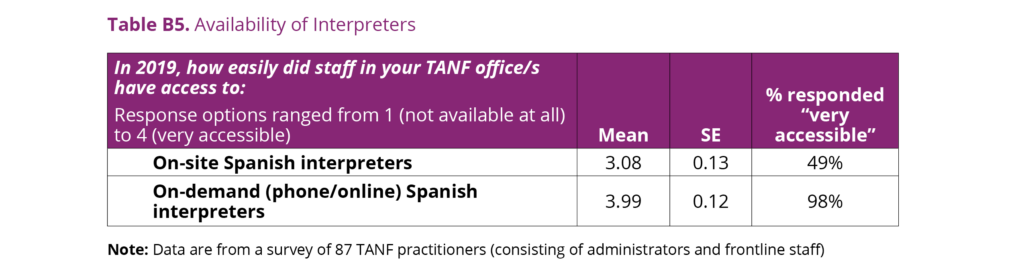

The TANF program application is available in-person and online via smartphone and computer. Practitioners (64%) reported that online applications are used most frequently by Hispanic applicants in general, but in-person applications are most common among Spanish-speaking Hispanic applicants (68%) [see Table B3]. Practitioners reported that the online and in-person applications seemed to be the most easily accessible options in Spanish, compared to applications via mail, phone, and smartphone applications. (93% of participants rated in-person and online applications as “very accessible,” while 50% rated smartphone applications as “very accessible” [see Table B4].) Additionally, 98 percent of practitioners reported that language interpreters are very accessible for phone interpretation, but only 49 percent perceived that language interpreters are very accessible in-person (see Table B5).

Despite these limitations, practitioners generally felt that navigating the TANF program application process is relatively easy for non-English speaking applicants. However, there were some differences in perceptions between administrators and frontline staff—or between those who create policy versus those who implement and carry out TANF program processes.

- Administrators perceived the entire process (application, follow-up, etc.) to be slightly easier than frontline staff who maintain direct contact with applicants. Administrators also perceived Spanish materials to be more available than their frontline counterparts (see Table B2).

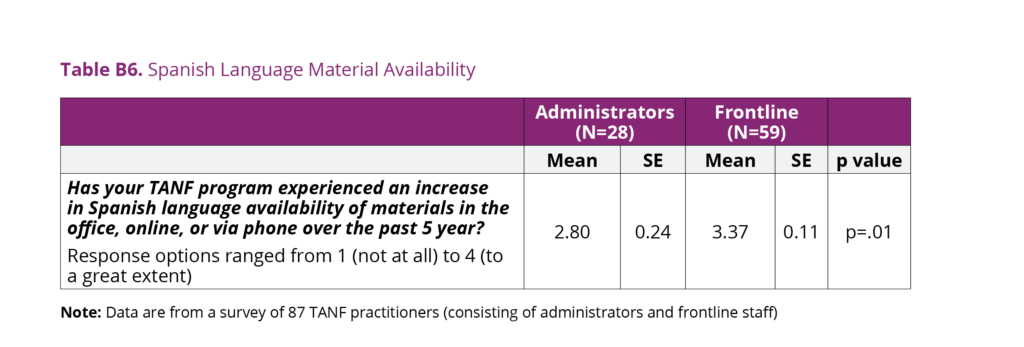

- Frontline staff perceived a greater increase in the number of Spanish language materials over the past five years than administrators, which may suggest that frontline staff are seeking or using alternatives to translation (see Table B6).

Immigration-related challenges

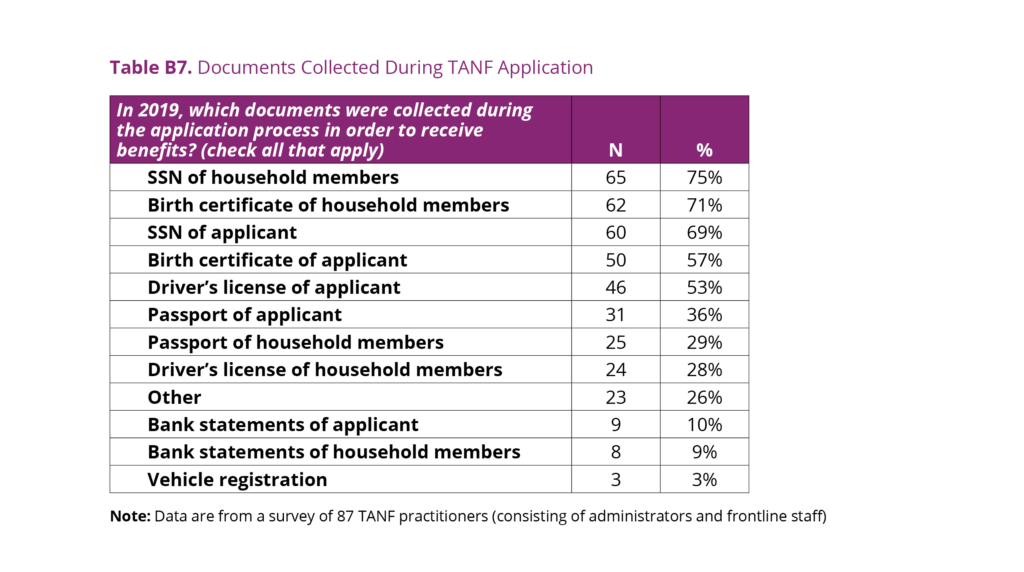

Concerns around immigration—for example, immigration enforcement practices or the public charge rule—may discourage some people from seeking out public benefits, including eligible citizens who may not be U.S.-born.11,12 Although the initial online TANF program application does not require the SSNs of household members who are not requesting assistance, many offices collect information that may make applicants feel vulnerable.

- More than half of practitioners reported collecting birth certificates (57%) and more than two thirds reported collecting the SSN of the applicant as required documentation (69%).

- Nearly three quarters of practitioners reported collecting both birth certificates (71%) and SSNs from household members as required documentation for application (75%) [see Table B7].

Strategies to improve access and engagement of Hispanic families

![]() Outreach. One of the key factors identified by practitioners as impacting TANF program utilization among Hispanic families is families’ awareness of available programs. Targeted, language-accessible outreach and education about the TANF program may represent essential strategies for increasing access to TANF cash assistance among eligible families. In our survey, practitioners perceived that media outreach targeted specifically to the Hispanic population seldom occurs. Despite this, practitioners reported that Hispanic people are generally aware of their programs. Some important nuances include:

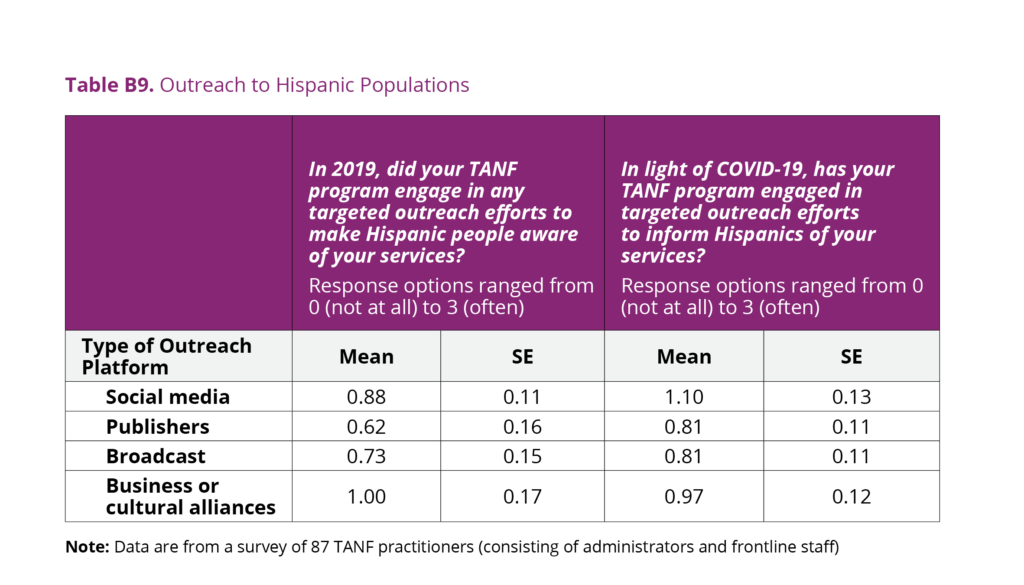

Outreach. One of the key factors identified by practitioners as impacting TANF program utilization among Hispanic families is families’ awareness of available programs. Targeted, language-accessible outreach and education about the TANF program may represent essential strategies for increasing access to TANF cash assistance among eligible families. In our survey, practitioners perceived that media outreach targeted specifically to the Hispanic population seldom occurs. Despite this, practitioners reported that Hispanic people are generally aware of their programs. Some important nuances include:

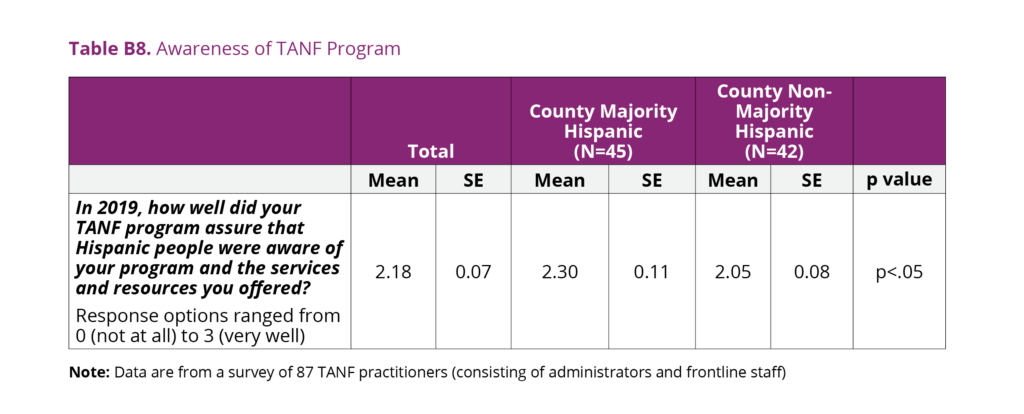

- Practitioners in majority-Hispanic counties perceive that more Hispanic individuals are aware of their programs than in non-majority Hispanic counties [see Table B8].

- Media outreach to the Hispanic population is perceived to have increased slightly from March to June 2020, during the early part of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States [see Table B9].

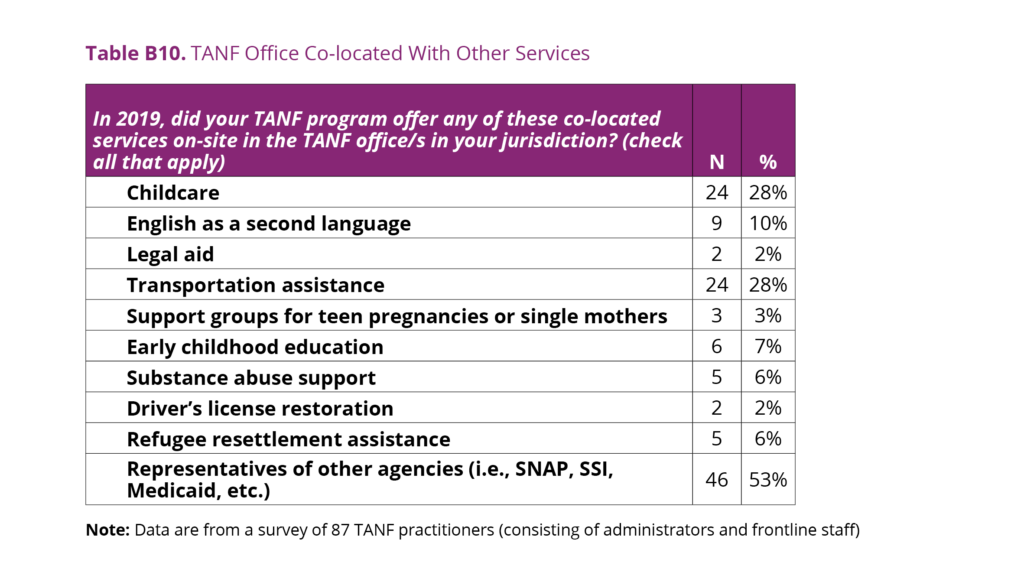

![]() TANF program integration with other public benefits. Many families who utilize the TANF program also qualify for and use other public benefits, such as SNAP; the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC); and Medicaid. In New Mexico, 90 percent of TANF program recipient families also receive SNAP benefits, just under 98 percent receive medical assistance, 13 percent receive subsidized housing, and 6 percent receive child care subsidies.13 Co-locating offices and integrating the application process and service delivery for all such programs may help families better access the full range of services available to them. In fact, more than half of practitioners (53%) reported that TANF program offices are co-located with other public assistance programs [see Table B10].

TANF program integration with other public benefits. Many families who utilize the TANF program also qualify for and use other public benefits, such as SNAP; the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC); and Medicaid. In New Mexico, 90 percent of TANF program recipient families also receive SNAP benefits, just under 98 percent receive medical assistance, 13 percent receive subsidized housing, and 6 percent receive child care subsidies.13 Co-locating offices and integrating the application process and service delivery for all such programs may help families better access the full range of services available to them. In fact, more than half of practitioners (53%) reported that TANF program offices are co-located with other public assistance programs [see Table B10].

In response to open-ended questions, a majority of practitioners reported that Hispanic families find it equally easy (or easier) to access SNAP, WIC, or Medicaid as to access TANF benefits. However, some practitioners highlighted that WIC applications are a separate process in New Mexico, whereas TANF, SNAP, and Medicaid are all part of the same application—which theoretically makes them easier to access. However, participation in WIC is generally higher among Hispanic populations, suggesting that its separation from other public benefits might be beneficial.

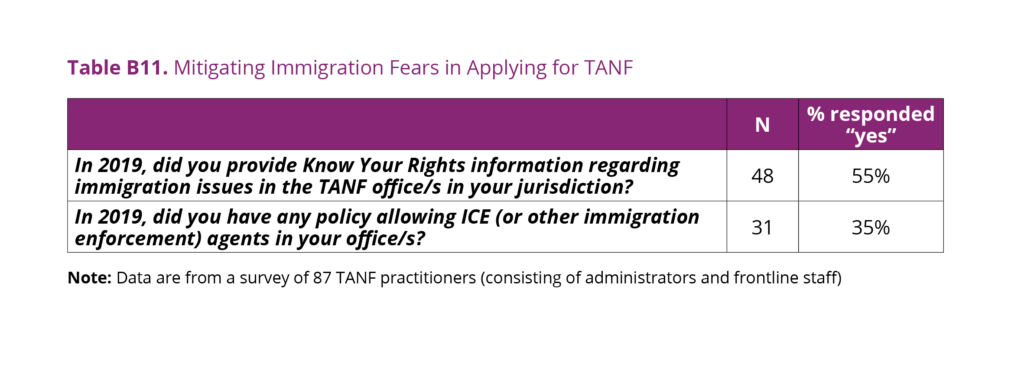

![]() Mitigate families’ fears in applying for TANF. Practitioners identified office policies and practices that can mitigate some of the fears associated with applying for government benefits.14 For example, Know Your Rights information can clarify the impact of public benefits use on immigration status and documentation requirements.15 Similarly, an office policy that prevents Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) from entering the premisesg can help build trust.

Mitigate families’ fears in applying for TANF. Practitioners identified office policies and practices that can mitigate some of the fears associated with applying for government benefits.14 For example, Know Your Rights information can clarify the impact of public benefits use on immigration status and documentation requirements.15 Similarly, an office policy that prevents Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) from entering the premisesg can help build trust.

- More than half of practitioners reported that their office provides Know Your Rights info (e.g., education and information about an individual’s rights in the context of encounters with immigration officials) on immigration issues (55%).

- Just over one third of practitioners said they have policies prohibiting ICE from entering their offices (35%) [see Table B11].

Practitioner-identified Barriers to Access

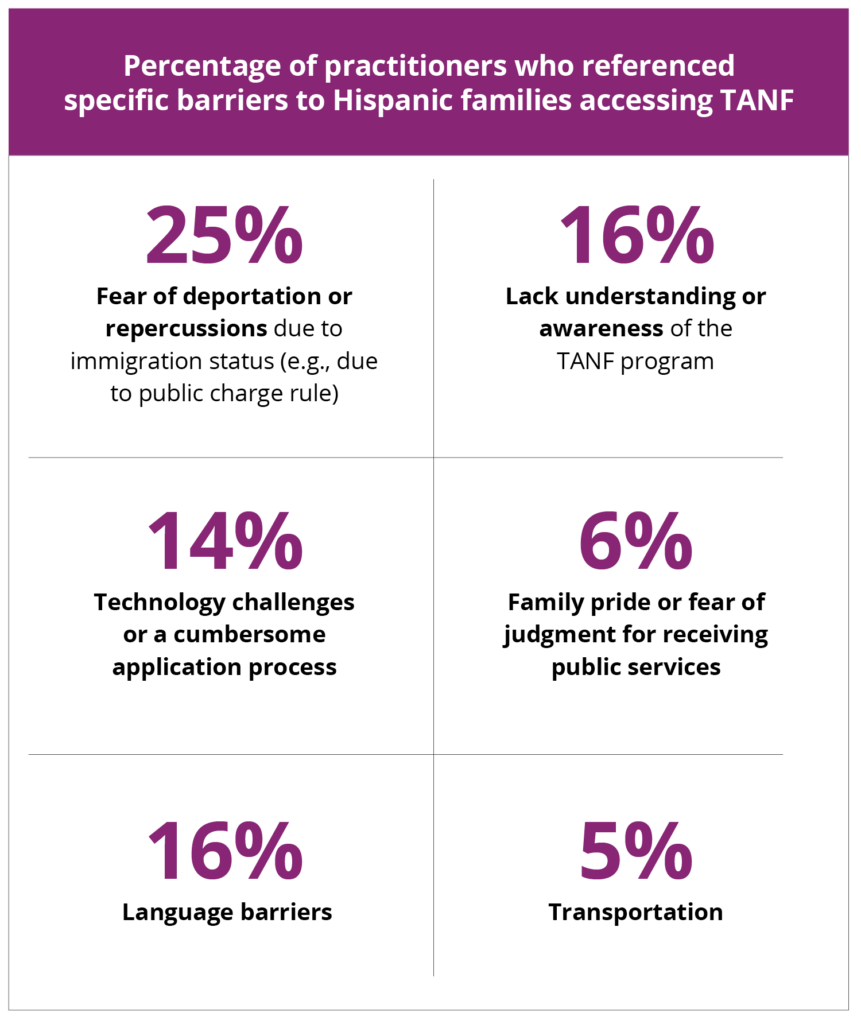

A majority of practitioners (67 of the 87 who completed the survey) also completed three open-ended questions included at the end of the survey, which asked them to identify both barriers to access to the TANF program and ways to improve access for Hispanic families.h Analyses of the open-ended responses were performed to validate patterns of responses into reasonable categories using NVivo (not shown). Many of the barriers and recommendations mirror findings that emerged from the close-ended portion of the survey, discussed above.

Although some practitioners did not identify any challenges to accessing the TANF program for Hispanic families, most (54%) acknowledged various barriers. Specific barriers are included in the table below.

Practitioners offered strategies to overcome some of the aforementioned barriers and improve access to the TANF program for Hispanic families.

Increase access to on-site Spanish-speaking staff. One practitioner reflected, “I believe we need people who are fluent in Spanish to work with Spanish speaking families/individuals. I do not think calling a language line helps; instead, it makes them [families] feel like a number and not a person. Also, we need people trained properly in how to communicate effectively with this population so they understand what is expected of them and that we are here to help.” Another practitioner recommended “partnering Hispanic families, if Spanish speaking, with Spanish speaking case workers who are proficient, knowledgeable, and able to communicate the program better than someone who is not as proficient, or [better than] some language line representative who [is] not interested in helping the customer.”

Increase access to online TANF program information in Spanish—for example, through “a more integrated website that is word for word in Spanish next to its English language [translation].”

Increase outreach on information about the TANF program, including on social media and television. Outreach targeting Latino communities that explains program benefits was one of the key approaches referenced by practitioners (39% of responses) who responded to the open-ended questions on making access to TANF easier for Hispanic families. Specific recommendations included the following:

- “More advertisement regarding TANF; access to computers and phones”

- “More local outreach efforts in Hispanic communities” and “more community outreach targeting Hispanic families”

- “More exposure for the programs available and what the requirements are”

- “More information available to [families] other than in office—maybe pamphlets or online information”

- “The program [should be] shared on social media and television. The clearness of the program [should] be explained or made clear who to contact. Also, case workers need to be more knowledgeable.”

Address families’ fear of deportation and loss of citizenship opportunity. One practitioner stated, “If Hispanic households (especially Hispanic households with immigrant or undocumented members) were not in fear of being deported or losing opportunity to be a citizen, I think it would make it easier for them to take the step to apply. They have access to applications and generous help with applications. ISD does its part to help as soon as possible and discrimination is not tolerated in our agency.”

Address confidentiality of information. One respondent reflected that applicants should know that “the information they provide is secured.”

Conclusion

Given its history and context as a majority-Hispanic state, New Mexico offers a unique lens with which to examine Hispanic engagement in public benefit programs such as TANF. A survey of TANF practitioners highlighted several characteristics of New Mexico’s public benefits approach that may serve as a model for improving equitable access to Hispanic families in other states and in local jurisdictions. The designation of a centralized immigration specialist position and local immigration ambassadors is particularly notable and might represent an innovative way to respond to the particular needs of New Mexico’s immigrant population. Streamlining services with other programs with higher uptake among Hispanic families, such as WIC, may also support Hispanic families’ access to human service programs such as TANF. However, such a strategy must be considered carefully so as not to inadvertently reduce uptake in both types of benefits.

Despite the fact that many program staff are Hispanic, equitable language and literacy access to program materials remain at least somewhat of a challenge in New Mexico. Stages in the application process that ask for SSNs may also interfere with follow-through, despite families’ initial application to receive services. Access to translation and interpretation services does not necessarily provide the same level of accessibility as support from culturally competent and bilingual staff. It is also notable that even in New Mexico—with its larger percentage of Hispanic residents and a relatively immigration-friendly policy context—there is a deep concern around immigration status and its implications for accessing TANF program benefits.

Footnotes

a We use “Hispanic” and “Latino” interchangeably throughout the brief. Consistent with the U.S. Census definition, this includes individuals who have origins in Mexico, Puerto Rico, and Cuba, as well as other “Hispanic, Latino or Spanish” origins.

b The TANF program practitioner survey in New Mexico is part of a broader endeavor to administer the same survey to TANF program practitioners in several other states, funded by the WT Grant Foundation. https://childandfamilypolicy.duke.edu/research-item/social-assistance-hispanic-youth/

c A number of outcomes are possible during the eligibility determination in immigrant households. Benefit amounts are adjusted according to the number of U.S. citizens in the household, with some exceptions. For example, full benefits may be granted for individuals with refugee status.

d For more about public charge rules see https://www.uscis.gov/archive/public-charge-fact-sheet.

e New Mexico reported spending 20 percent of its TANF block grant and state maintenance-of-effort funds on basic assistance in 2019. New Mexico’s other categories of spending in 2019 include Pre-K and Head Start (21%), tax credits (20%), and child care (14%); New Mexico spent the least on child welfare (0.1%), administration and systems (2%), work supports and supportive services (3%), work activities (7%), and other services (12%).17

f Findings demonstrated remarkable consistency across many state-level characteristics. No differences in survey responses were identified across regions by county poverty levels, population size, or political party affiliation, suggesting relative uniformity in TANF policy implementation across the state.

g While Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) can enter public areas of a business (e.g., lobbies, waiting areas, etc.), they cannot enter private areas of a business unless they possess a judicial warrant (i.e., signed by a court/judge). Agencies can implement policies and procedures to ensure that their employees and clients are aware of this distinction and what to do in these situations.

h (1) In your opinion, what are the key barriers that Hispanic families face in accessing your TANF program? (2) In your opinion, which approaches might make it easier for Hispanic families to access TANF? (3) In your opinion, is it harder or easier for eligible Hispanic families to access SNAP, WIC, or Medicaid?

Suggested Citation

Finno-Velasquez, M., Gennetian, L., Sepp, S., & Deambrosi, S. (2021). Practitioners in New Mexico’s TANF Program Offer Perspectives on Engaging Hispanic Families. Report 2021-03. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. Retrieved from www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/practitioners-in-new-mexicos-tanf-program-offer-perspectives-on-engaging-hispanic-families

References

1 Office of Family Assistance, Office of the Administration for Children & Families. (2020a). About TANF. Retrieved from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ofa/programs/tanf/about

2 Gennetian, L. A., Hill, Z., & Ross-Cabrera, D. (2020). State-level TANF policies and practice may shape access and utilization among Hispanic families. Report 2020-06. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. Retrieved from www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/state-level-tanf-policies-and-practice-may-shape-access-and-utilization-among-hispanic-families

3 New Mexico Human Services Department. (n.d.) Temporary assistance for needy families. Retrieved from https://www.hsd.state.nm.us/lookingforassistance/temporary_assistance_for_needy_families/

4 Statista Research Department. (2021). Percentage of Hispanic population in the United States in 2019, by state. Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/259865/percentage-of-hispanic-population-in-the-us-by-state/

5 U.S. Census Bureau. (2018c). 2018 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table DP05; Retrieved from https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=race&g=0400000US35&tid=ACSDP5Y2018.DP05&hidePreview=false

6 U.S. Census Bureau. (2018d). 2018 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table S1601. Retrieved from https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=ACSST1Y2019.S1601&g=0100000US.04000.001&tid=ACSST5Y2018.S1601&hidePreview=true

7 U.S. Census Bureau. (2018b). 2018 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table DP02. Retrieved from https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=foreign%20born&g=0400000US35,35.050000&tid=ACSDP5Y2018.DP02&hidePreview=true

8 Annie E. Casey Foundation, Kids Count Data Center. (2019a). Children below 200 percent poverty in New Mexico. Retrieved from https://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/tables/47-children-below-200-percent-poverty?loc=33&loct=2#detailed/2/33/false/1729,37,871,870,573,869,36,868,867,133/any/329,330

9 Annie E. Casey Foundation, Kids Count Data Center. (2019b). Children in poverty by race and ethnicity in New Mexico. https://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/tables/44-children-in-poverty-by-race-and-ethnicity?loc=33&loct=2#detailed/2/33/false/1729,37,871,870,573,869,36,868,867,133/10,11,9,12,1,185,13/324,323

10 Pew Research Center. (2014). Demographic and economic profiles of Hispanics by state and county, 2014: New Mexico. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/states/state/nm

11 Haley, J. M., Kenney, G. M., Bernstein, H., & Gonzalez, D. (2020). One in five adults in immigrant families with children reported chilling effects on public benefit receipt in 2019. Washington, DC: Urban Institute. Retrieved from http://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/102406/one-in-five-adults-in-immigrant-families-with-children-reported-chilling-effects-on-public-benefit-receipt-in-2019.pdf

12 Perreira, K. M., & Pedroza, J. M. (2019). Policies of Exclusion: Implications for the Health of Immigrants and Their Children. Annual review of public health, 40, 147–166. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-044115

13 Office of Family Assistance, Office of the Administration for Children & Families. (2020b). Characteristics and financial circumstances of TANF recipients, fiscal year 2019. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/ofa/resource/characteristics-and-financial-circumstances-of-tanf-recipients-fiscal-year-2019

14 Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. (2021). State fact sheets: How states spend funds under the TANF block grant. https://www.cbpp.org/research/family-income-support/state-fact-sheets-how-states-spend-funds-under-the-tanf-block-grant

15 Crosnoe, R., Pedroza, J. M., Purtell, K., Fortuny, K., Perreira, K. M., Ulvestad, K., … & Chaudry, A. (2012). Promising practices for increasing immigrants’ access to health and human services. US Department of Health and Human Services.

16 Held, M. L., Nulu, S., Faulkner, M., & Gerlach, B. (2020). Climate of fear: Provider perceptions of Latinx immigrant service utilization. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 1-12. https://txicfw.socialwork.utexas.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Held_et_al-2020-Journal_of_Racial_and_Ethnic_Health_Disparities.pdf

Appendix A

The NMHSD ISD provided researchers with a list of 121 administrative and frontline staff to survey from each of New Mexico’s 33 counties, including three statewide TANF policy/program managers; five regional managers; and a county director, a family assistance/TANF liaison worker, an immigration ambassador, and a contracted employment assistance specialist in each field office. The survey was distributed in June 2020. A total of 87 practitioners—including 28 administrators and 59 frontline staff—completed the survey, for a response rate of 76 percent among administrators and 70 percent among frontline staff.

Appendix B

The tables below show the responses of the 87 practitioners (consisting of administrators and frontline staff) to close-ended questions about their perceptions of Hispanic applicants and which organizational practices they felt facilitated or impeded TANF program access among Hispanic families in their communities. The tables showing means are reporting the average response from practitioners across a range of scales used to assess the answer to each question. For example, in Table B1, we see that on a scale of 1 (not at all common) to 5 (extremely common), practitioners reported a score of 2.7, on average, in response to a question about how common it was for Hispanic applicants to arrive with someone who could serve as translator.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the Steering Committee of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, along with Melissa Perez and Kristen Harper for their helpful edits, comments, and research assistance at multiple stages of this project. We would also like to than the State of New Mexico Human Services Department Income Support Division for their helpful review and cooperation.

Editor: Brent Franklin

Designer: Catherine Nichols

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Megan Finno-Velasquez, PhD, MSW, is an Assistant Professor and Director of the Center on Immigration and Child Welfare in the School of Social Work at New Mexico State University, in Albuquerque, NM. Dr. Finno-Velasquez has spent the past 14 years working at the intersection of child welfare and immigration issues, as a child welfare practitioner, administrator, and researcher. In 2019, Dr. Finno-Velasquez was appointed Director of Immigration Affairs for the New Mexico Children, Youth and Families Department in a position split with her professorship at NMSU, where she is working to build an immigration unit to improve policies and practices to support immigrant and refugee children along the Mexico border and throughout the state.

Lisa Gennetian, PhD, is a co-investigator of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, leading the research area on poverty and economic self-sufficiency. She is the Pritzker Associate Professor of Early Learning Policy Studies at Duke University Sanford School of Public Policy. One of her research foci is income instability among children and families, the ways this is informed by theories emerging from behavioral economics, and implications for social policy and programs.

Sophia Sepp, LMSW, MPH, CHES is the Program Manager at the Center on Immigration and Child Welfare (CICW) at New Mexico State University (NMSU). She is a graduate of the dual Master of Social Work and Master of Public Health program at NMSU. She received a Bachelor of Science in Foreign Service with a focus on international politics at Georgetown University in 2014. An interest and passion for immigration issues and their impacts on children and families brought her to the U.S-Mexico borderlands, where she has served at various community organizations who work to provide support to children and families impacted by the unique social and health disparities of the region.

Santiago Deambrosi completed the work related to this brief as an Associate in Research at Duke Sanford Center for Child and Family Policy.

ABOUT THE CENTER

The National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families (Center) is a hub of research to help programs and policy better serve low-income Hispanics across three priority areas: poverty reduction and economic self-sufficiency, healthy marriage and responsible fatherhood, and early care and education. The Center is led by Child Trends, in partnership with Duke University, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, and University of Maryland, College Park. The Center is supported by grant #90PH0028 from the Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation within the Administration for Children and Families in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families is solely responsible for the contents of this brief, which do not necessarily represent the official views of the Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, the Administration for Children and Families, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Copyright 2021 by the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families.