Oct 4, 2017

Research Publication

One Quarter of Hispanic Children in the United States Have an Unauthorized Immigrant Parent

Authors:

Overview

Today, 18 million Hispanica children live in the United States, and they account for one quarter of all children.1,2 An overwhelming majority (94 percent) of Latino children were born in the United States.3 However, that is not the case for their parents. In fact, about half of Latino children have at least one parent who was born in another country,4 some of whom are not authorized to live in the United States. As the nation continues to engage in crucial discourse over the future of immigration policy, it is important to acknowledge the extent to which these policies will affect the well-being of the vast number of children whose parents may be at risk of deportation.

In this brief, we draw on publicly available information from several data sources to estimate the proportion of U.S. Latino children who have at least one parent who is an unauthorized immigrant. Our conclusion: about one quarter—25 to 28 percent—of all Latino children in the United States have an unauthorized immigrant parent. This translates to more than 4 million Hispanic children—a finding consistent across each data source and the three different approaches we used to create the estimate. In short, about 1 in 4 of America’s Hispanic children are at risk for experiencing the stresses associated with having a parent who is an unauthorized immigrant. (Throughout this brief, we use the term unauthorized immigrant parents to describe parents who lack legal status to live in the country.)

Why focus on Latino children in our estimate of children with an unauthorized immigrant parent? Two reasons stand out:

- First, although immigration from Latin Americab (especially from Mexico) has declined substantially in recent years,5 the majority of unauthorized immigrants living in the United States come from Latin American countries.6,7 This means that any changes in immigration policies and enforcement will have a disproportionate impact on the Latino community.8-10

- Second, Hispanics are the largest and one of the fastest-growing racial/ethnic minority groups among children in the United States.11-13 They also represent a growing segment of the nation’s future workforce.14 If present trends continue, by 2060 nearly one third of the nation’s workforce will be Latino.15,16 How Latino children fare will be critical to our nation’s social and economic development.

Why the number matters

Latino children with immigrant parents—even those who are unauthorized immigrants—have many strengths. For example, Hispanic children with one or more immigrant parent, including those who are poor, are more likely than Latino children with only U.S.-born parents to be in a two-parent family with at least one working adult.17,18 Additionally, recent estimates indicate that 72 percent of the unauthorized immigrant population is in the labor force, meaning there is often an employed adult in the household.6 These family structures promote healthy child development and adult well-being.19,20

Still, research suggests that the challenges associated with having an unauthorized immigrant parent are linked to a wide range of adverse developmental and educational experiences,21 primarily brought about by poverty.22,23 Children living with unauthorized immigrant parents are disproportionately poor.24 About three quarters have families with incomes that fall at or near poverty.24 Out of fear of drawing attention to their immigration status, their parents may not access public assistance programs designed to meet the needs of vulnerable children.25-28

Research also tells us that safe, secure, and stable attachments to parents and caregivers are critical for children’s healthy development.29-32 Children with an unauthorized immigrant parent, who face the possibility of separation from their parents, are at risk of experiencing stress and anxiety based on that fear or reality.23,33,34 This kind of uncertainty, stress, and trauma can threaten children’s well-being, affecting their brain development, physical health, and more.35-38 Additionally, should large numbers of parents be deported, states may be faced with placing their children in foster care, a public system that in most states is already overextended.

Children with at least one unauthorized immigrant parent may also be at risk of experiencing cognitive delays, struggles in school, and depression or anxiety.21-23,33,39-42 Despite these challenges, prospects for children with an unauthorized immigrant parent may still be better than they would have been if their parents had never come to the United States. Many unauthorized parents come from countries with social upheaval or economic distress.43

Getting to the number

Methodology

Here are details about the three approaches and multiple sources we used to uncover the proportion of Hispanic children who have an unauthorized immigrant parent. We used several approaches and sources in order to confer confidence in the estimate, which we found to be consistent across all approaches.

Approach 1: Combining estimates from the Pew Research Center and the Current Population Survey

Our first approach builds upon existing estimates from the Pew Research Center. Specifically, Pew Research Center estimated that overall, 5.5 million children under the age of 18 in the United States in 2010 had an unauthorized immigrant parent. Of these children, 87 percent had parents who were born in Latin America.44 Taken together, these two estimates (i.e., 5.5 million * .87) indicate that 4.8 million Hispanic children had a parent who was an unauthorized immigrant in 2010.

According to the 2010 Current Population Survey (CPS), there were 17.1 million Hispanic children under age 18 in the United States in 2010.45 Dividing the number of Hispanic children with a parent who was an unauthorized immigrant by the overall number of Hispanic children (4.8 million/17.1 million) indicates that approximately 28 percent of all Hispanic children in the United States had an unauthorized immigrant parent in 2010.

Approach 2: Linking information from the Department of Homeland Security and the American Community Survey

Our second approach links statistical information derived from a Department of Homeland Security (DHS) report and from the American Community Survey (ACS). According to the DHS report, 9.6 million unauthorized immigrants from Latin America lived in the United States in 2012.46 ACS estimates indicate that 21.3 million Latin American immigrants lived in the nation that same year.3 Together, these numbers suggest that 45 percent of Latin American immigrants (9.6 million/21.3 million) were unauthorized in 2012.c

Using the 2012 ACS, we estimated that approximately 55 percent of Hispanic children living in the nation in 2012 had at least one immigrant parent.48,49 The proportion of Hispanic immigrants who are unauthorized and the proportion of Hispanic children with immigrant parents are related, but not directly comparable. However, if we make some assumptions about the family formation patterns and ethnic classification of immigrants, this information provides insight into the prevalence of Hispanic children with an unauthorized parent. We applied the following assumptions to calculate a conservative estimate:

- Unauthorized immigrants have the same number of children per person as do other immigrants.d

- Unauthorized immigrants from Latin America only have children with unauthorized immigrants from Latin America.

- Children of immigrants are counted by the Census as Hispanic if and only if their parents come from Latin America.

These assumptions imply a 1-to-1 correspondence between the proportion of immigrants from Latin America who were unauthorized and the proportion of Hispanic children of immigrants who had an unauthorized parent. Given these assumptions, along with estimates of the proportion of Hispanic immigrants who were unauthorized (45 percent) and the proportion of Hispanic children with an immigrant parent (55 percent), we found that 25 percent of Hispanic children had an unauthorized immigrant parent (.45 * .55) in 2012, translating to roughly 4.3 million Hispanic children (.25 * 17.5 million, the number of Hispanic children estimated in the ACS in 2012).

We tailored this same approach to focus on U.S.-born Hispanic children, as well as to provide country-ofheritage-specific estimates. Using the 2012 ACS, we found that 52 percent of U.S.-born Hispanic children had an immigrant parent—compared with 55 percent for all Hispanic children.48,49 Again, in 2012, 45 percent of Latin American immigrants were unauthorized. Together, this information suggests that 23 percent (.52 x .45) of U.S.-born Hispanic children had a parent who was an unauthorized immigrant in 2012.

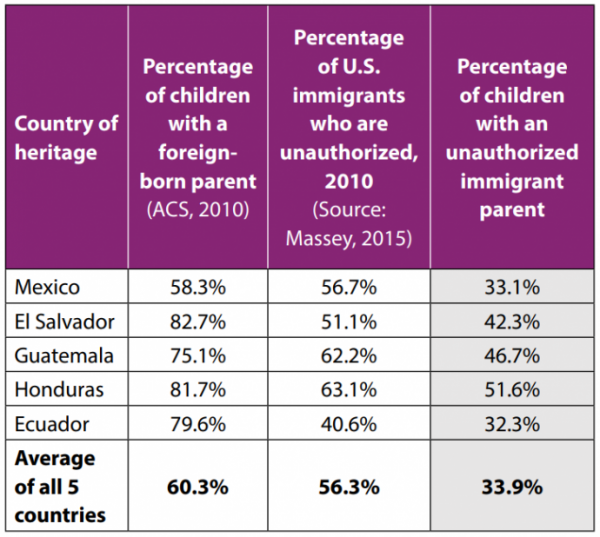

Most unauthorized immigrants from Latin America come from Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Ecuador.46 Douglas Massey, leading expert on immigration flows from Latin America to the United States, estimated that 56 percent of immigrants from these five countries were unauthorized in 2010.47 By matching this estimate with 2010e population estimates of the percentage of Hispanic children with heritage in these five countries who had an immigrant parent (see Table 1), we found that 34 percent (.56 x .60) of children with heritage in any of these five countries had a parent who was an unauthorized immigrant in 2010. Roughly 1 in 3 children of Mexican and Ecuadorian heritage, 2 in 5 children of Salvadorian and Guatemalan heritage, and more than half of children of Honduran heritage had an unauthorized immigrant parent in 2010.

Table 1. Estimates of the number of Hispanic children with an unauthorized immigrant parent from five Latin American countries

Approach 3: Extrapolating from the Survey of Income and Program Participation

Our third approach to estimating the proportion of Hispanic children in the U.S. who have an unauthorized immigrant parent or parents is based on data from the 2008 Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP). The SIPP is the only federal nationally representative survey that directly asks people about their immigration status.50 Although respondents are not asked whether they are unauthorized immigrants, the information provided can be used to identify Hispanic parents who seem likely to fit this category. The SIPP links adults to children who live with them, which enables one to estimate the share of Hispanic children who live with an unauthorized immigrant parent.

SIPP respondents were asked whether they were U.S. citizens or permanent residents (“green card holders”). Respondents were classified as unauthorized immigrants if they declined to identify as citizens or permanent residents and if they lacked other indicators that suggest authorized status, such as being a government employee or participating in public programs.51,52

SIPP respondents were asked whether they were U.S. citizens or permanent residents (“green card holders”). Respondents were classified as unauthorized immigrants if they declined to identify as citizens or permanent residents and if they lacked other indicators that suggest authorized status, such as being a government employee or participating in public programs.51,52

Applying appropriate survey weights, we estimated that 8.6 percent of all adult immigrants were unauthorized immigrants from Latin America.53 We also estimated that these unauthorized Hispanic immigrants were parents of 10 percent of all children in the SIPP sample. It is important to note that both estimates (i.e., that of parents and that of children) may be low, since unauthorized immigrant status is based on what respondents said about themselves on a sensitive topic. However, the ratio between the two estimates is meaningful. If the birth rates among SIPP respondents are comparable to those of the population more broadly, we can scale up this ratio to approximate the proportion of Hispanic children with an unauthorized immigrant parent.

DHS and the Pew Research Center estimated that 9.6 million unauthorized immigrants of Latin American heritage lived in the United States in 2008, accounting for 24.2 percent of all immigrants.10,54 This ratio of unauthorized Latin American immigrants to all immigrants was 2.8 times that estimated using the SIPP (24.2 percent/8.6 percent). In the same way, the share of Hispanic children with an unauthorized immigrant parent was 2.8 times larger than what was found in the SIPP (2.8* 10 percent). From this, we estimated that 28 percent of Hispanic children had an unauthorized immigrant parent in 2008.f

(8.6%)/(10.0%)=(24.1%)/?

? = 28.0%

Conclusion

Approximately 1 in 4 U.S. Latino children have a parent who is an unauthorized immigrant, a finding that is striking in its consistency across data sources and methods. This means that there are more than 4 million Latino children in the United States who are at risk of experiencing parental separation and the stress and fear associated with their family’s uncertain legal status.

We also found that the likelihood of a Latino child having an unauthorized immigrant parent varies by country of heritage, suggesting varying levels of risk to children’s wellbeing. In 2010—the most recent year data are available by county of heritage—the proportion of Latino children with a parent who was an unauthorized immigrant parent ranged from 1 in 3 among children with Mexican heritage to roughly 1 in 2 among children with Honduran roots. These patterns reflect our nation’s immigration history as well as the factors that have shaped migration from specific countries.55,56 For example, while there is a long history of Mexican migration to the United States, significant levels of migration from Central American countries are more recent and driven by civil war, violence, and dire economic conditions.43,57

As our nation continues the important discourse about how to move forward on immigration policy, it is critical that we acknowledge the extent to which Latino children are disproportionately affected by these policies, and the potential impact of various policy alternatives on their short- and long-term well-being. This will matter not only for Latino children’s well-being, but also for the social and economic well-being of our nation.

Notes

a We use the terms Hispanic and Latino interchangeably, except when referring to information derived from federal data sources that use the term Hispanic.

b Latin America includes Central America, South America, and the Caribbean.

c This method of comparing DHS and Census estimates is adapted from Massey (2015).47DHS reported that 8.9 million people born in North America and 0.7 million people born in South America were unauthorized immigrants in the United States. Unauthorized Canadian immigrants were included, but comprised 1 percent of the unauthorized immigrant population in the United States.

d Some research suggests that unauthorized immigrants, who tend to be younger than people in the general population, have more children than authorized immigrants or non-immigrants. If unauthorized immigrants have higher rates of childbearing, in general, than others, the proportion of Hispanic children with an unauthorized immigrant parent will be higher. Thus, we have applied the most conservative assumption to derive this estimate.

e 2010 is the most recent year for which estimates of the unauthorized population by country of origin are available.

f A multiple imputation approach, which takes into account other characteristics of unauthorized immigrants, yields a similar estimate: 28.6 percent (available upon request).53

Methodological Concerns

It is important to note some limitations to the

approaches used in this analysis:

- First, all three approaches use published DHS and

Pew Research Center estimates of the number

of unauthorized immigrants living in the United

States.a,b,c Both entities used the same underlying

methodd to arrive at an estimate of the size of

the unauthorized population. The DHS and Pew

Research Center reports consistently found a

population of 11 to 12 million unauthorized

immigrants. - Second, although the three approaches use distinct

Census surveys (CPS, ACS, and SIPP), these surveys

used the same Census Bureau sampling frame.

Thus, these surveys share limitations to sampling

the unauthorized population. - Third, given the lack of direct data on the legal

status of residents in the country and the difficulty

associated with collecting such data, we rely

heavily on assumptions. The degree to which our

assumptions are incorrect will affect our estimates.

However, we believe that the assumptions are

conservative, reasonable, and supported by

existing research. - Fourth, we cannot assign statistical error margins to

our estimates because they are based on composites

of published estimates that do not all report error

margins. The consistency of the different estimates,

however, provides some reassurance about the

precision of the underlying techniques.

a Passel, J. S., & Cohn, D. (2011). Unauthorized immigrant population: National and

state trends, 2010. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2011/02/01/unauthorized-immigrant-population-brnational-and-state-trends-2010/

b Baker, B., & Rytina, N. (2013). Estimates of the unauthorized immigrant population residing in the United States: January 2012. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics. Retrieved from

https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/Unauthorized%20Immigrant%20Population%20Estimates%20in%20the%20US%20January%202012_0.pdf

c Hoefer, M., Rytina, N., & Baker, B. C. (2009). Estimates of the unauthorized

immigrant population residing in the United States: January 2008. Retrieved from

https://www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/statistics/publications/ois_ill_pe_2008.pdf

d Passel, J. S. (2013). Unauthorized immigrants: How Pew Research counts

them and what we know about them. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

Retrieved from http://www.pewresearch.org/2013/04/17/unauthorized-immigrants-how-pew-research-counts-them-and-what-we-know-about-them/

References

References

1 US Census Bureau. (2015). American Community Survey 2015 1-year Estimates: B01001- Sex by Age (Hispanic/Latino). Retrieved from https://factfinder.census.gov/

2 US Census Bureau. (2015). American Community Survey 2015 1-year Estimates: B01001- Sex by Age. Retrieved from https://factfinder.census.gov/

3 US Census Bureau. (2012). American Community Survey 2012 1-Year Estimates: B05003I -Sex by Age by Nativity and Citizenship Status (Hispanic or Latino). Retrieved from https://factfinder.census.gov

4 Federal Interagency Forum on Child and Family Statistics. (2016). America’s Children in Brief: Key National Indicators of Well-Being, 2016, Table FAM4. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. Retrieved from https://www.childstats.gov/americaschildren/tables/fam4.asp

5 Massey, D. S. (2012). Immigration and the great recession. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality. Retrieved from https://web.stanford.edu/group/recessiontrends/cgi-bin/web/sites/all/themes/barron/pdf/Immigration_fact_sheet.pdf

6 Passel, J. S., & Cohn, D. V. (2014). Unauthorized immigrant totals rise in 7 states, fall in 14: Decline in those from Mexico fuels most state decreases. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewhispanic.org/2014/11/18/unauthorized-immigrant-totals-rise-in-7-states-fallin-14/

7 Migration Policy Institute. (n.d.). Profile of the Unauthorized Population: United States. Retrieved from http://www.migrationpolicy.org/data/unauthorizedimmigrant- population/state/US

8 Passel, J. S., & Cohn, D. (2016). Overall number of US unauthorized immigrants holds steady since 2009. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewhispanic.org/2016/09/20/overallnumber-of-u-s-unauthorized-immigrants-holdssteady-since-2009/

9 Lopez, G., & Patten, E. (2015). The impact of slowing immigration: Foreign-born share falls among 14 largest US Hispanic origin groups. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewhispanic.org/2015/09/15/the-impact-of-slowingimmigration-foreign-born-share-falls-among-14- largest-us-hispanic-origin-groups/

10 Passel, J. S., & Cohn, D. (2009). A portrait of unauthorized immigrants in the United States. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewhispanic.org/files/reports/133.pdf

11 Krogstad, J. M., & Lopez, M. H. (2014). Hispanic Nativity Shift. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewhispanic.org/2014/04/29/hispanic-nativity-shift/

12 Brown, A. (2014). U.S. Hispanic and Asian populations growing, but for different reasons. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/06/26/u-s-hispanicand-asian-populations-growing-but-for-differentreasons/

13 Patten, E. (2016). The Nation’s Latino Population Is Defined by Its Youth. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewhispanic.org/2016/04/20/the-nations-latino-population-isdefined-by-its-youth/

14 Colby, S. L., & Ortman, J. M. (2015 ). Projections of the size and composition of the US population: 2014 to 2060 Washington, DC: US Census Bureau. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/demo/p25-1143.pdf

15 Passel, J. B., & Cohn, D. V. (2008). U.S. Population Projections: 2005-2050. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewhispanic.org/2008/02/11/us-population-projections-2005-2050/

16 Toossi, M. (2016). A Look At The Future Of The U.S. Labor Force To 2060. Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/spotlight/2016/a-look-at-the-future-of-the-us-laborforce-to-2060/pdf/a-look-at-the-future-of-the-uslabor-force-to-2060.pdf

17 Karberg, E., Guzman, L., Cook, E., Scott, M., & Cabrera, N. (2017). A Portrait of Latino Fathers: Strengths and Challenges. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. Retrieved from https://hispanicrescen.wpengine.com/?publications=aportrait-of-latino-fathers-strengths-and-challenges7

18 Karberg, E., Cabrera, N., Fagan, J., Scott, M. E., & Guzman, L. (2017). Family Stability and Instability among Low-Income Hispanic Mothers With Young Children. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. Retrieved from https://hispanicrescen.wpengine.com/?publications=family-stability-and-instabilityamong-low-income-hispanic-mothers-with-youngchildren

19 Thomson, E., Hanson, T. L., & McLanahan, S. S. (1994). Family structure and child well-being: Economic resources vs. parental behaviors. Social Forces, 73, 222-242.

20 Fomby, P., & Cherlin, A. (2007). Family instability and child well-being. American Sociology Review, 71(2),181-204.

21 Yoshikawa, H., Suárez-Orozco, C., & Gonzales, R. G. (2016). Unauthorized Status and Youth Development in the United States: Consensus Statement of the Society for Research on Adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 47(1), 4-19.

22 Yoshikawa, H., & Kalil, A. (2011). The effects of parental undocumented status on the developmental contexts of young children in immigrant families. Child Development Perspectives, 5(4), 291-297.

23 Suárez-Orozco, C., Yoshikawa, H., Teranishi, R., & Suárez-Orozco, M. (2011). Growing up in the shadows: The developmental implications of unauthorized status. Harvard Educational Review, 81(3), 438-473.

24 Capps, R., Fix, M., & Zong, J. (2016). A profile of U.S. children with unauthorized immigrant parents. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Retrieved from http://www.migrationpolicy.org/research/profileus-children-unauthorized-immigrant-parents

25 Williams, S. (2013). Public assistance participation among U.S. children in poverty, 2010. Bowling Green, Ohio: National Center for Family & Marriage Research. Retrieved from http://www.bgsu.edu/content/dam/BGSU/college-of-arts-and-sciences/NCFMR/documents/FP/FP-13-02.pdf

26 Alvira-Hammond, M., & Gennetian, L. (2015). How Hispanic parents perceive their need and eligibility for public assistance. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. Retrieved from https://hispanicrescen.wpengine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/2015-46Hisp-Ctr-Perceptions-Eligibility.pdf

27 Perreira, K. M., Crosnoe, R., Fortuny, K., Pedroza, J., Ulvestad, K., Weiland, C., et al. (2012). Barriers to immigrants’ access to health and human services programs. Washington, DC: Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation. Retrieved from http://www.urban.org/publications/413260.html

28 Earner, I. (2007). Immigrant families and public child welfare: Barriers to services and approaches for change. Child Welfare, 86(4), 63.

29 Bowlby, J. (2008). A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development. New York: Basic Books.

30 Main, M., & Cassidy, J. (1988). Categories of response to reunion with the parent at age 6: Predictable from infant attachment classifications and stable over a 1-month period. Developmental Psychology, 24(3), 415.

31 Armsden, G. C., & Greenberg, M. T. (1987). The inventory of parent and peer attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 16(5), 427-454.

32 Ainsworth, M. D. S., & Bell, S. M. (1970). Attachment, exploration, and separation: Illustrated by the behavior of one-year-olds in a strange situation. Child Development, 41(1), 49-67.

33 Potochnick, S. R., & Perreira, K. M. (2010). Depression and anxiety among first-generation immigrant Latino youth: key correlates and implications for future research. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 198(7), 470.

34 Chaudry, A., Capps, R., Pedroza, J., Castaneda, R., Santos, R., & Scott, M. (2010). Facing our future: Children in the aftermath of immigration enforcement. Washington, DC: The Urban Institute. Retrieved from http://www.urban.org/publications/412020.html

35 Ortega, A. N., Horwitz, S. M., Fang, H., Kuo, A. A., Wallace, S. P., & Inkelas, M. (2009). Documentation status and parental concerns about development in young US children of Mexican origin. Academic Pediatrics, 9(4), 278-282.

36 Shonkoff, J. P., & Phillips, D. A. (2000). From neurons to neighborhoods: The science of early childhood development. National Academies Press.

37 Aldwin, C. M. (2007). Stress, coping, and development: An integrative perspective. New York: Guilford Press.

38 Schore, A. N. (2001). The effects of early relational trauma on right brain development, affect regulation, and infant mental health. Infant Mental Health Journal, 22(1-2), 201-269.

39 Arbona, C., Olvera, N., Rodriguez, N., Hagan, J., Linares, A., & Wiesner, M. (2010). Acculturative stress among documented and undocumented Latino immigrants in the United States. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 32(3), 362-384.

40 Gonzales, R. G., Suárez-Orozco, C., & Dedios-Sanguineti, M. C. (2013). No place to belong: Contextualizing concepts of mental health among undocumented immigrant youth in the United States. American Behavioral Scientist, 57(8), 1174-1199.

41 Gonzales, R. G. (2011). Learning to be illegal undocumented youth and shifting legal contexts in

the transition to adulthood. American Sociological Review, 76(4), 602-619.

42 Crosnoe, R. (2006). Health and the education of children from race/ethnic minority and immigrant families. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 47(1), 77-93.

43 Batalova, G. L. a. J. (2017). Central American Immigrants in the United States. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute. Retrieved from http://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/central-american-immigrants-united-states

44 Passel, J. S., & Cohn, D. (2011). Unauthorized immigrant population: National and state trends, 2010. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewhispanic.org/files/reports/133.pdf

45 US Census Bureau. (2010). Current Population Survey. Table 1. Population by Sex, Age, Hispanic Origin, and Race: 2010. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2010/demo/hispanic-origin/2010-cps.html

46 Baker, B., & Rytina, N. (2013). Estimates of the unauthorized immigrant population residing in

the United States: January 2012. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Office of Immigration Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/ois_ill_pe_2012_2.pdf

47 Massey, D. (Ed.). (2015). The real Hispanic challenge. In Hispanics in America: A report card on poverty, mobility, and assimilation (3-7). Stanford, CA: Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality.

48 National Research Center on Hispanic Children and Families’ analysis of Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 6.0.

49 Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 6.0.

50 Wildsmith, E., Ansari, A., & Guzman, L. (2015). Improving data infrastructure to recognize hispanic diversity in the United States. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. Retrieved from http://www.childtrends.org/?publications=improving-datainfrastructure-to-recognize-hispanic-diversity-in-theunited-states

51 Bachmeier, J. D., Van Hook, J., & Bean, F. D. (2014). Can we measure immigrants’ legal status? Lessons from two US surveys. International Migration Review, 48(2), 538-566.

52 Hall, M., Greenman, E., & Farkas, G. (2010). Legal status and wage disparities for Mexican immigrants. Social Forces, 89(2), 491-513.

53 National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Familes’ analysis of data from the 2008 Survey of Income and Program Participation. (2014).

54 Hoefer, M., Rytina, N., & Baker, B. C. (2009). Estimates of the unauthorized immigrant population residing in the United States: January 2008. Retrieved from https://www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/statistics/publications/ois_ill_pe_2008.pdf

55 Portes, A., & Rumbaut, R. G. (2006). Immigrant America: A portrait. Berkely, CA: Univ of California Press.

56 Massey, D. S. (1995). The new immigration and ethnicity in the United States. Population and

Development Review, 21(3), 631-652.

57 Massey, D. S., Durand, J., & Malone, N. J. (2002). Beyond smoke and mirrors: Mexican immigration in an era of economic integration. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Randy Capps, the Steering Committee of the National Research Center on Hispanic

Children & Families, staff within the Administration for Children and Families, and an anonymous reviewer, all of whom

provided valuable review and insights to earlier drafts of this brief. Additionally, we thank Claudia Vega and Emily Miller

for their excellent research assistance at multiple stages of this project.

Editors: Harriet Scarupa, August Aldebot-Green

Copyeditor: John Lingan

Designer: Catherine Nichols