Oct 11, 2023

Research Publication, Research Series

Many Hispanic Households With Low Income Access No-Cost or Low-Cost Care, Yet Nearly One in Four Face High Out-of-Pocket Costs

Authors:

This brief draws on national data to examine weekly out-of-pocket costs for child care among Hispanic households with low incomes and compare them to an established threshold for care affordability. Among our findings, our analysis suggests that, while many Hispanic households with low incomes were able to access low- or no-cost care in 2019, those who did pay out-of-pocket faced very high cost burdens.

Introduction

Child carea—especially that which is of high quality—serves a critical dual purpose for families, supporting both parental employment and children’s development.1,2 As recognized in a recent White House Executive Order, the costs of providing and obtaining such care are significant,3 making affordability a key driver of child care access and a matter of national policy concern given its importance to families and the economy.4 For many Hispanicb families, who tend to have high levels of employment but low levels of income,5,6 child care costs can pose a barrier to securing and maintaining high-quality arrangements. In addition, the nature of many low-wage jobs—which often involve nonstandard, variable, and/or unpredictable work schedules—can further limit families’ access to affordable care that meets both parents’ and children’s needs.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) defines affordable child care as that which requires families to pay no more than 7 percent of their household income.7 Yet nationally, the average annual cost of full-time child care in 2021 was $10,600,8 an amount equivalent to 10 percent of the average income for a two-parent household and 35 percent for a single-parent household. This cost burden is even greater for families using more expensive types of care, such as center-based care and infant care. Key federal and state programs intended to reduce out-of-pocket child care costs for families with low incomes include Head Start public pre-kindergarten programs and Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) subsidies. While these public investments in child care have expanded over the last several years, current funds reach only a fraction of eligible children and evidence shows that Latino families tend to be underserved by some of these programs.9,10

In this brief, we use data from the 2019 National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE) to report on the affordability of child care for a national sample of Latino households with low income who used nonparental care arrangements on a regular basis (at least 5 hours per week) for children up to age 13, and had at least one child younger than age 6 and not yet in kindergarten. Within this sample, we examine families’ weekly out-of-pocket costs as a proportion of their household income and compare this to the federal guideline for affordable child care (7% or less of total income). We then look at whether child care affordability varies by three features of families’ care arrangements (number of hours, number of providers, and type of care) and across three potential drivers of child care costs (whether the household includes members who are immigrants, family income level, and the presence of children younger than age 3 in the home). Prior research shows that child care is most expensive for families with children under the age of 3.11 Additionally, households with immigrant members and those with either very low incomes or incomes just above eligibility thresholds may experience challenges locating child care they can afford.12

Key Findings

As the most recent national data available on what households spend on child care, the NSECE 2019 provides an important accounting of child care affordability for families in the United States following decades of increased, but relatively limited, public investments in early childhood13 and just prior to the global COVID-19 pandemic. Taken together, our findings suggest a need for sustained and varied investments to support affordable child care access for Hispanic families with low incomes. While public subsidies appear to offset costs for some families, many Latino families either rely on unpaid providers or spend an exceedingly high percentage of their budget on child care, both of which may result in precarious or unsustainable arrangements. Specifically, we find that:

Hispanic ECE Data Series

This brief draws on nationally representative data from the 2019 National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE) to describe multiple aspects of child care access and utilization for Hispanic low-income households with young children. The series presents estimates on the availability, flexibility, and affordability of care, as well as the characteristics of settings and providers who serve Hispanic children. These descriptive analyses update similar analyses focused on ECE access for Latino families that drew from 2012 NSECE data. For more information, readers are encouraged to review other reports in the series, as well as our synthesis on child care access for Latino families.

While many Hispanic households with low incomes used no-cost child care in 2019, those who paid out-of-pocket tended to face very high costs.

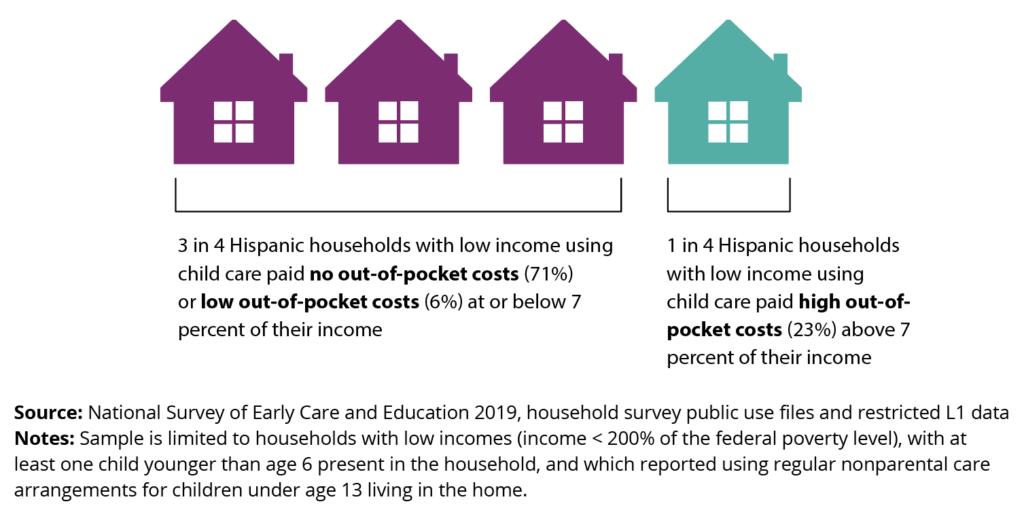

- The majority of Latino households with low incomes (77%) using regular child care in 2019 had affordable arrangements; in other words, these households paid 7 percent or less of household income for care. Most of these households (71%) had no out-of-pocket cost burden because they used providers who were either unpaid or paid through another source (e.g., publicly or privately subsidized care). In addition, a small percentage of households (6%) had low cost burden: These households paid something out-of-pocket for care, but their costs were at or below the 7 percent of income affordability threshold.

- Still, roughly 1 in 4 Hispanic households with low incomes who used care in 2019 (23%) had high child care cost burden, with their out-of-pocket costs exceeding 7 percent of their income. On average, this group spent roughly 30 percent of their household income on child care.

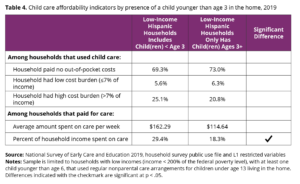

Child age is a key driver of child care affordability for Latino households with low incomes; high costs were more prevalent for families with infants and toddlers than for families with preschool-aged or older children.

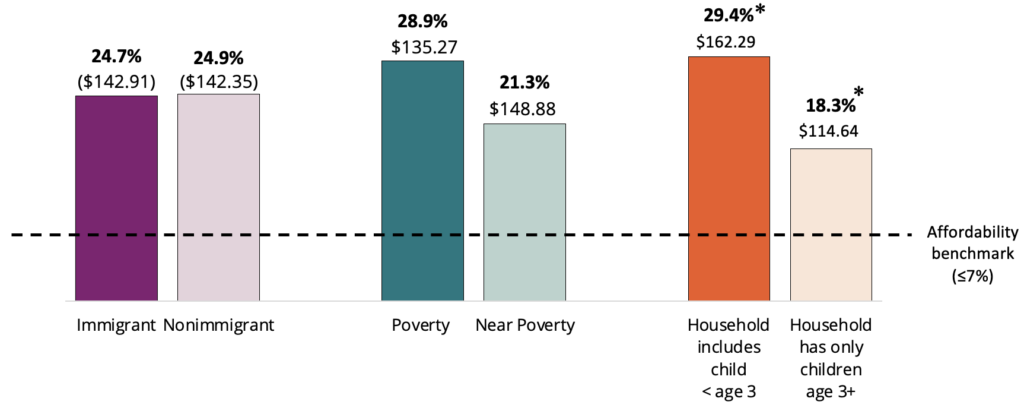

- Among Hispanic households with low incomes who paid out-of-pocket for care, those with at least one child under age 3 spent a significantly higher percent of household income on care (30%) than those with only children ages 3 or older (18%).

- Indicators of affordability of child care for Hispanic households with low incomes were generally similar across household poverty levels; they also varied little based on whether the household includes immigrants.

While many Hispanic households with low incomes use unpaid home-based care arrangements, we found evidence that public investments to reduce child care costs helped some Hispanic families access center-based arrangements; these investments may be especially effective in reaching children in immigrant households.c

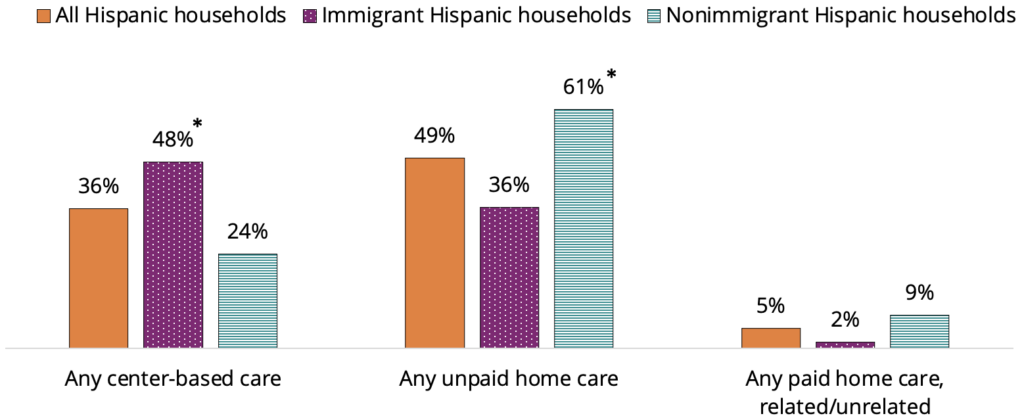

- Among Hispanic households with low incomes who paid no out-of-pocket child care costs, nearly half used unpaid home-based care (49%) and more than one third used center-based care (36%). Center care provided at no charge to families is very likely to be publicly subsidized through programs such as Head Start, state pre-kindergarten, and CCDF subsidies.

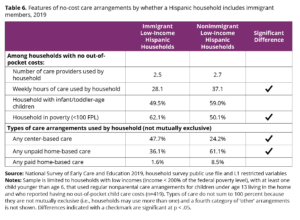

- The types of no-cost care arrangements accessed by Hispanic households varied by whether the household included immigrant members. We found that a larger share of immigrant Hispanic households used no-cost center care (48%) compared to non-immigrant households (24%). Conversely, a larger share of non-immigrant households (61%) than immigrant households (36%) used unpaid home-based care.

Results

Share of Hispanic households with low incomes who had no out-of-pocket child care costs, a low cost burden, or a high cost burden

In 2019, roughly 3 in 4 Hispanic households with low incomes using child care had no out-of-pocket costs (71%) or low out-of-pocket costs (6%), paying 7 percent or less of their income on care. In contrast, nearly 1 in 4 Hispanic households (23%) had a high care cost burden that exceed 7 percent of their income. (See Figure 1 below, and Table 1 at the end of this brief.)

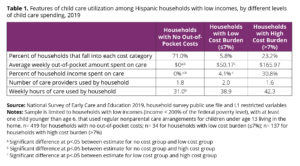

Given that differences in household spending on child care may partly reflect households’ use of different amounts of care, we examined average weekly hours of care and number of providers across the three levels of care spending (i.e., no, low, or high costs). We found that all families in all three groups used more than 30 hours of care per week and used an average of roughly two providers (see Table 1). The only statistically significant difference in amount of care used was that households with no out-of-pocket costs used fewer hours of care per week, on average, than households with high cost burden (31 hours versus 42 hours, respectively).

Figure 1. In 2019, 3 in 4 Hispanic households with low incomes using child care had no or low out-of-pocket child care costs, while 1 in 4 paid high out-of-pocket costs for care

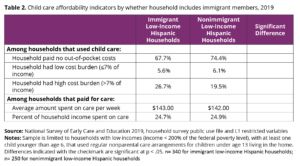

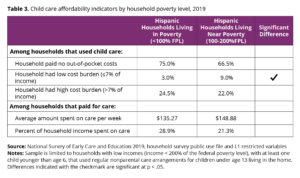

Child care affordability for Hispanic households with low incomes, by whether a household member is an immigrant, poverty status, and child age composition

Among the 3 in 10 Hispanic households with low incomes who paid out-of-pocket for child care in 2019, many had unaffordable child care costs—especially those with infants and toddlers (Figure 2). On average, Hispanic households with low incomes who paid for child care in 2019 spent a much higher percentage of their income (upwards of 20%) than is considered affordable by federal guidelines (7% or less). Average child care costs, as a percent of household income or in dollars, did not differ significantly by whether a Hispanic household included immigrant members, or by poverty status (Tables 2 and 3) a smaller share of households living in poverty (<100% of the federal poverty level) had affordable costs compared to households in near poverty (100-200% of the federal poverty level) (3% versus 9%). Notably, Hispanic households with low incomes who had children younger than age 3 spent a higher percent of their income on child care (29%) than those with only children ages 3 or older (18%) (Table 4).

Figure 2. Among Hispanic households with low incomes who paid for child care in 2019, average costs were high, especially among those with children under age 3

Average weekly child care costs (as percent of household income and in dollars) among Hispanic households with low incomes that paid out-of-pocket for care, by immigrant status, poverty status, and child age

Source: National Survey of Early Care and Education 2019, household survey public use files and restricted L1 data

Source: National Survey of Early Care and Education 2019, household survey public use files and restricted L1 data

Notes: Sample is limited to households with low incomes (income < 200% of the federal poverty level), with at least one child younger than age 6 present in the household, and which reported using regular nonparental care arrangements for children under age 13 living in the home. Pairwise differences were tested between Hispanic immigrant and nonimmigrant households. Differences indicated with “*” are significant at p < .05.

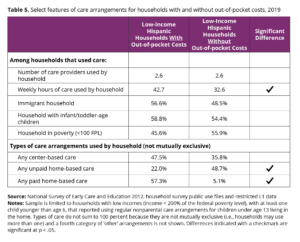

Types of care arrangements used by Hispanic households with low incomes, both with and without out-of-pocket costs

In 2019, many Hispanic households with low incomes and no out-of-pocket child care costs used unpaid home-based providers, although more one third used at least some center-based care. Families using no-cost child care arrangements (no out-of-pocket expenditures) may do so for a variety of reasons. Some may use unpaid family, friend, or neighbor care out of necessity (to meet affordability or availability needs) and/or because of preference for such providers; others may use paid arrangements that are fully subsidized through public or private funding sources. While the current data do not directly assess the extent to which cost influenced families’ decisions to use some arrangements over others, we examined the types of arrangements used by Hispanic households with low incomes, both with and without out-of-pocket costs (Table 5). These descriptive analyses show that households paying for care used, on average, more hours of care per week (43 hours) than households without out-of-pocket costs (33 hours); paying households were more likely to use paid home-based providers (57% versus 5%) and less likely to use unpaid home-based providers (49% versus 22%). Notably, rates of center-based care use did not differ across households with and without out-of-pocket costs.

More than one third (36%) of Hispanic households with low incomes and no out-of-pocket child care costs used center-based arrangements, suggesting that federal and state investments designed to increase ECE access by reducing or eliminating costs for families are reaching many Hispanic households with low incomes. Given 2012 NSECE findings suggesting that immigrant and nonimmigrant Hispanic households access somewhat different types of no-cost arrangements, we replicated that comparison with the 2019 NSECE data (Table 6). We found that a larger share of immigrant Hispanic households used no-cost center care (48%) relative to nonimmigrant households (24%). At the same time, a larger share of nonimmigrant households used unpaid home-based care (61%) relative to immigrant households (36%) (Table 6, Figure 3). Finally, a small share of Hispanic households with no out-of-pocket costs reported using paid home-based care arrangements (5%), suggesting that the costs of these arrangements may have been subsidized (e.g., CCDF child care subsidies).

Figure 3.Among Hispanic households with low incomes and no out-of-pocket child care costs, immigrant households were more likely to use center-based arrangements, with nonimmigrant households more likely to use unpaid home-based care

Types of child care used by Hispanic families with no out-of-pocket costs, by whether household includes immigrant members

Source: National Survey of Early Care and Education 2019, household survey public use files and restricted L1 data Notes: Sample is limited to households with low incomes (income < 200% of the federal poverty level), with at least one child younger than age 6 present in the household, and which reported using regular nonparental care arrangements for children under age 13 living in the home. Pairwise differences were tested between Hispanic immigrant and nonimmigrant households. Differences indicated with “*” are significant at p < .05.

Source: National Survey of Early Care and Education 2019, household survey public use files and restricted L1 data Notes: Sample is limited to households with low incomes (income < 200% of the federal poverty level), with at least one child younger than age 6 present in the household, and which reported using regular nonparental care arrangements for children under age 13 living in the home. Pairwise differences were tested between Hispanic immigrant and nonimmigrant households. Differences indicated with “*” are significant at p < .05.

Conclusion

As a recent White House Executive Order asserts, access to affordable, high-quality child care is essential to the well-being of children, families, and the economy3. Hispanic households with young children have high employment rates even among families with very low incomes,14 highlighting a pressing need for affordable child care among this population. However, information is limited about Hispanic families’ child care expenditures and the types of arrangements they can access within their budget, leaving policymakers with incomplete data on issues of equity and child care affordability. In our analysis of national data from 2019 presented in this brief, we found that many Hispanic households with low incomes relied on care arrangements that require little or no out-of-pocket costs, but that those who did purchase care tended to have a high cost burden. Nearly one quarter of Hispanic households with low incomes using child care spent more than the federal affordability guideline of 7 percent or less of household income, paying an average of 30 percent of their income. These results for Hispanic families generally align with broader national estimates of child care affordability, which show that many families with low incomes rely on no-cost care arrangements; when these families do spend out-of-pocket, though, it is at a higher cost burden than can be considered affordable and often higher than what is experienced by families with more income.15

In this brief, we explored a small set of factors potentially associated with different levels of child care spending among Hispanic households with low incomes. Specifically, we examined three household characteristics possibly linked to constrained access to affordable care (immigrant status, poverty level, and child age) and found that Hispanic households with children younger than age 3 are more likely to experience high cost burden than those with children who are preschool-age and older. This finding is consistent with research documenting an inadequate ECE supply for infants and toddlers, with costs to families that often exceed those for college tuition.16 The lack of affordable care options for this age group is estimated to result in economic losses of more than $122 billion nationally in terms of lost parental income, employer productivity, and revenue.17

We also explored the types of arrangements used by the large share of Hispanic households with low incomes who do not pay out-of-pocket for care. The use of no-cost care may reflect a variety of factors. Some families may prefer care provided in-kind by a family member or friend, while others may choose this type of care when other options to meet employment and/or children’s developmental needs are unaffordable or unavailable. Alternately, some families using no-cost arrangements may be able to do so because of public investments that subsidize costs (e.g., Head Start, public Pre-K, or CCDF-subsidized care). While the current data do not allow us to tease out the complex set of factors driving child care selections among Hispanic parents with low incomes, we found that just under half of households with no-cost arrangements used unpaid home care and more than one third used free center-based care. While both settings address affordability, the services offered by center- and home-based ECE providers can differ substantially in terms of quality, availability, and flexibility.18,19

Our results align with conceptual frameworks describing families’ child care selections not as unconstrained decisions, but rather as a series of accommodations and trade-offs between affordability, availability, quality, and parent preferences.20 These accommodations are made in the context of ECE supply factors that include varied access to publicly subsidized care.21 In 2019, 1 in 3 Hispanic households (and 1 in 2 Hispanic households with members who were immigrants) with low incomes and no out-of-pocket care costs used center-based arrangements; this provides evidence that public investments intended to address affordability and improve ECE access are likely reaching some Hispanic communities, with the potential for greater reach if policy efforts expand these investments, especially for families with infants and toddlers. One study of Hispanic household engagement with the child care market in Chicago showed that even families regarded as “hard to reach” because of their household immigrant status and/or limited English will participate in publicly funded ECE programs if they are offered such care in accessible and culturally and linguistically responsive ways.22

Despite encouraging signs that public funds can make formal ECE programs more accessible to Hispanic households who are interested in using them, most Hispanic families with low incomes still use either unpaid home providers or arrangements that come with a high cost burden. These finding may reflect the fact that, similar to other parents in the low-wage workforce, many Hispanic parents have nontraditional, irregular, and/or unpredictable work hours.23 These types of work schedules do not tend to align well with more formal ECE programs and providers, which typically operate during standard weekday hours; this misalignment can necessitate a patchwork of multiple care arrangements that can be precarious for parents and children and may be associated with greater child care expenses.24 Along with increased funding for existing subsidized child care, greater investments in home-based providers (e.g., subsidies and other resources) could improve the stability and quality of this sector of the child care market, which provides essential support to many working families.

Since the 2019 NSECE data were collected, the costs of living and household goods—such as rent and food—have continued to rise, further stretching the limited budgets of households with low incomes. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated existing ECE supply issues as providers left the field and programs closed, with evidence that such losses disproportionately impacted Hispanic communities.25,26 Despite significant federal investments to mitigate the pandemic’s impact, the ECE workforce has not yet recovered to pre-pandemic levels, meaning that families will likely continue to face significant challenges finding affordable child care that meets their needs.27 Expanding access to no- and low-cost high-quality child care arrangements for working families remains an important policy priority to achieve poverty reduction and bolster the economy, and our results in this analysis suggest that such efforts could benefit many Hispanic households with low incomes.

Data Source and Methodology

The 2019 National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE) is a set of four surveys designed to provide a national portrait of the early care and education landscape in the United States from both ECE providers’ and households’ perspectives. The data in this report were drawn from the NSECE public use household survey, which contains parent-/caregiver-reported information about child care costs, utilization, and other household characteristics. Level 1 restricted NSECE data were used to examine variation between Hispanic households in which all members were born within the United States and those households with one or more members who were born outside the United States. The household survey is nationally representative of families with children under age 13 and the sample design oversampled low-income areas, yielding a large sample of households with low incomes.

This report focuses on Hispanic households considered to have low incomes (defined as those with an annual income below 200% of the federal poverty threshold) that have at least one child from birth to age 5 not yet in kindergarten, and which reported using nonparental care regularly (at least 5 hours per week) at the time of the survey. Using these criteria, the analytic sample for this analysis contains 590 Hispanic households with available data for indicators of affordability. Just over half of this sample of Hispanic families have at least one household member (51%) born outside the United States, with the remaining having all U.S.-born household members (49%).

Affordability and child care cost data are presented at the household level and capture all regular nonparental care arrangements used for any children ages 13 or younger who live in the home. Descriptive pairwise differences are noted in the text, figures, and tables. All analyses were conducted in Stata and were weighted to be representative of children living in U.S. households in 2019.

Definitions

Hispanic households are defined as those in which the survey respondent identified all members of the household as being of Hispanic heritage. Multi-racial or multi-ethnic households (which may include Hispanic members) are not included in the current analysis to help with interpretability and clarity of the results.

Households with low incomes are those that reported an annual income below 200 percent of the federal poverty threshold.

Regular nonparental care is defined by the NSECE study and in this analysis as any nonparental care arrangements used on a regular basis for 5 or more hours per week. This includes various types of center- and home-based arrangements, as well as other types of regularly scheduled nonparental care (e.g., organizational ECE settings, extracurriculars, or school-based care).

Immigrant Hispanic households captures those in which the respondent reported that at least one household member had been born outside of the United States.

Weekly household out-of-pocket child care expenses were calculated by summing reported household spending for each nonparental care arrangement used for any child younger than age 13 living in the home. This variable does not include subsidies or subsidy reimbursements and only considers out-of-pocket costs.

Households using only no-cost child care arrangements identifies households with no out-of-pocket child care expenses for any arrangement being used. No-cost arrangements can include publicly funded programs (e.g., Head Start, public pre-kindergarten) that do not charge parents a fee, arrangements fully subsidized with private or public funds (e.g., CCDF), and care provided free of charge by individual caregivers (e.g., grandparent care).

Child care costs as a percentage of household income were calculated to consider the share of families’ budgets that go toward child care. Households were further categorized using this continuous variable. Some households reported having no out-of-pocket costs because they were using care provided free of charge and/or using arrangements fully subsidized with private or public funds. Households spending 7 percent or less of their income on child care (i.e., the affordability benchmark recommended by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services)7 were identified as having affordable costs. Households paying more than 7 percent of their income are identified as having high (or unaffordable) costs.

Type of care arrangement. This set of non-mutually exclusive indicators captures whether the household used the following types of arrangements for any child in the home: (1) any center-based care; (2) any unpaid home-based care, which is often provided by family, friends, or neighbors; and/or (3) any paid home-based care provided by a related or unrelated individual. Center-based arrangements include all center- or organization-based care and home-based arrangements include care that occurs in the child’s home or the provider’s home, including family child care homes.

Footnotes

a We primarily use the term “child care” in this brief rather than “early care and education” because some of the arrangements included in this household-level analysis of costs may be for school-age children.

b We use “Hispanic” and “Latino” interchangeably throughout this report. The terms are used to reflect the U.S. Census definition to include individuals having origins in Mexico, Puerto Rico, and Cuba, as well as other “Hispanic, Latino or Spanish” origins.

c In this brief, we use the term “immigrant households” to refer to households with one or more members who are an immigrant, and the term ‘nonimmigrant households’ to refer to households in which all members were born in the United States.

Suggested Citation

Crosby, D., Stephens, C., & Mendez, J. (2023). Many Hispanic Households With Low Income Access No-Cost or Low-Cost Care, Yet Nearly One in Four Face High Out-of-Pocket Costs. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://doi.org/10.59377/768o8919u

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Steering Committee of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families—along with Julia Henly, Kehinde Akande, and Laura Ramirez—for their helpful comments, edits, and research assistance at multiple stages of this project. The Center’s Steering Committee is made up of the Center investigators—Drs. Natasha Cabrera (University of Maryland, Co-I), Danielle Crosby (University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Co-I), Lisa Gennetian (Duke University; Co-I), Lina Guzman (Child Trends and PI), Julie Mendez (University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Co-I), and Maria Ramos-Olazagasti (Child Trends and Building Capacity lead)—and federal project officers Drs. Ann Rivera, Jenessa Malin, and Mina Addo (Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation).

Editor: Brent Franklin

Designer: Catherine Nichols

About the Authors

Danielle Crosby, PhD, is a co-investigator of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, co-leading the research area on early care and education. She is an associate professor in the Department of Human Development and Family Studies at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Her research focuses on understanding how policies and systems shape early education access and quality for young children in low-income families.

Christina Stephens, , PhD, was previously a pre-doctoral fellow with the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, in the research area on early care and education. Christina’s research focuses on understanding the factors and policies that promote child care access and quality, particularly among low-income families with young children. She is now a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Virginia with the Education Science Training Program on English Learners (EL-VEST). A portion of her effort on this project was supported by the Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education, through Grant R305B210008 to the University of Virginia. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not represent views of the Institute or the U.S. Department of Education.

Julia Mendez, PhD, is a co-investigator of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, co-leading the research area on early care and education. She is a professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Her research focuses on risk and resilience among ethnically diverse children and families, with an emphasis on parent-child interactions and family engagement in early care and education programs.

About the Center

The National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families (Center) is a hub of research to help programs and policy better serve low-income Hispanics across three priority areas: poverty reduction and economic self-sufficiency, healthy marriage and responsible fatherhood, and early care and education. The Center is led by Child Trends, in partnership with Duke University, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, and University of Maryland, College Park. The Center is supported by grant #90PH0028 from the Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation within the Administration for Children and Families in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families is solely responsible for the contents of this brief, which do not necessarily represent the official views of the Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, the Administration for Children and Families, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Copyright 2023 National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families

Table 1. Features of Child Care Utilization Among Hispanic Households with Low Incomes, by Different Levels of Child Care Spending, 2019

Table 2. Child Care Affordability Indicators by Whether Household Includes Immigrant Members, 2019

Table 3. Child Care Affordability Indicators by Household Poverty Level, 2019

Table 4. Child Care Affordability Indicators by Presence of a Child Younger Than Age 3 in the Home, 2019

Table 5. Select Features of Care Arrangements for Households With and Without Out-of-Pocket Costs, 2019

Table 6. Features of No-Cost Care Arrangements by Whether a Hispanic Household Includes Immigrant Members, 2019

REFERENCES

1 Mendez Smith, J., Crosby, D., & Stephens, C. (2021). Equitable access to high-quality early care and education: opportunities to better serve young Hispanic children and their families. In L. Gennetian & M. Tienda (Eds.): Investing in Latino Youth. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science (AAPSS), 696(1), 80–105. Sage. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027162211041942

2 Mendez, J., Crosby, D., & Siskind, D. (2020). Work Hours, Family Composition, and Employment Predict Use of Child Care for Low-Income Latino Infants and Toddlers. National Research Center on Hispanic Children and Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/work-hours-family-composition-and-employment-predict-use-of-child-care-for-low-income-latino-infants-and-toddlers/

3 The White House. (April 18, 2023). Executive Order on Increasing Access to High-Quality Care and Supporting Caregivers. https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2023/04/18/executive-order-on-increasing-access-to-high-quality-care-and-supporting-caregivers/

4 Friese, S., Lin, V., Forry, N., & Tout, K. (2017). Defining and Measuring Access to High Quality Early Care and Education: A Guidebook for Policymakers and Researchers (No. 2017-08). Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/opre/report/defining-and-measuring-access-high-quality-early-care-and-education-ece-guidebook

5 Wildsmith, E., Ramos-Olazagasti, M.A., & Alvira-Hammond, M. (2018). The Job Characteristics of Low-Income Hispanic Parents. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. http://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/publications/the-job-characteristics-of-low-income-hispanic-parents/

6 Gennetian, L., Guzman, L., Ramos-Olazagasti, M., & Wildsmith, E. (2019). An Economic Portrait of Low-Income Hispanic Families: Key Findings from the First Five Years of Studies from the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. National Research Center on Hispanic & Families. https://hispanicrescen.wpengine.com/research-resources/an-economic-portrait-of-low-income-hispanic-families-key-findings-from-the-first-five-years-of-studies-from-the-national-research-center-on-hispanic-children-families.

7 Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) Program, 81 Fed. Reg. 67438 (September 30, 2016). https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2016-09-30/pdf/2016-22986.pdf

8 Haynie, K., Waterman, C., Ritter, J. (2023). The Year in Child Care: 2021 Data, Analysis and Recommendations. Child Care Aware of America. https://childcareaware.org/catalyzing-growth/

9 Adams, G., & Pratt, E. (2021). Executive Summary: Assessing Child Care Subsidies through an Equity Lens A Review of Policies and Practices in the Child Care and Development Fund. Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/104776/executive-summary-assessing-child-care-subsidies-through-an-equity-lens_1.pdf

10 Gillespie, C. (2019). Young Learners, Missed Opportunities: Ensuring That Black and Latino Children Have Access to High-Quality State-Funded Preschool. The Education Trust. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED603198.pdf

11 Workman, S. (2021). The True Cost of High-Quality Child Care Across the United States. Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/true-cost-high-quality-child-care-across-united-states/

12 Mendez, J., Crosby, D., & Siskind, D. (2020). Work Hours, Family Composition, and Employment Predict Use of Child Care for Low-Income Latino Infants and Toddlers. National Research Center on Hispanic Children and Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/work-hours-family-composition-and-employment-predict-use-of-child-care-for-low-income-latino-infants-and-toddlers/

13 Morrissey, T. (2019). The Effects Of Early Care And Education On Children’s Health. Health Affairs Health Policy Brief. https://doi.org/10.1377/hpb20190325.519221

14 Wildsmith, E., Ramos-Olazagasti, M.A., & Alvira-Hammond, M. (2018). The Job Characteristics of Low-Income Hispanic Parents. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. http://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/publications/the-job-characteristics-of-low-income-hispanic-parents/

15 Hardy, E. & Park, J. (2022). 2019 NSECE Snapshot: Child Care Cost Burden for U.S. Households for Children Under Age 5. OPRE Report #2022. Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/opre/report/2019-nsece-snapshot-child-care-cost-burden-us-households-children-under-age-5

16 Child Care Aware of America. (2022). Price of Care: 2021 child care affordability analysis. https://info.childcareaware.org/hubfs/Child%20Care%20Affordability%20Analysis%202021.pdf

17 Bishop, S. (2023). $122 Billion: The Growing Annual Cost of the Child Care Crisis. Council for a Strong America. https://strongnation.s3.amazonaws.com/documents/1598/05d917e2-9618-4648-a0ee-1b35d17e2a4d.pdf?1674854626&inline;%20filename=%22$122%20Billion:%20The%20Growing,%20Annual%20Cost%20of%20the%20Infant-Toddler%20Child%20Care%20Crisis.pdf%22

18 Tonyan, H. A., Paulsell, D., & Shivers E. M. (2017) Understanding and incorporating home-based child care into early education and development systems. Early Education and Development, 28(6), 633-639. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2017.1324243

19 Bayly, B. L., Bierman, K. L., & Jacobson, L. (2021). Teacher, center, and neighborhood characteristics associated with variations in Preschool quality in childcare centers. Child & Youth Care Forum, 50, 779-803. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-021-09599-0

20 Chaudry, A., Henly, J., & Meyers, M. (2010). Conceptual Frameworks for Child Care Decision-Making. ACF-OPRE White Paper. Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Washington, DC. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/opre/conceptual_frameworks.pdf

21 Chaudry, A., Pedroza, J., See, H., Danziger, A., Grosz, M., & Scott, M. (2011). The child care decisions of low-income families. The Urban Institute. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/27331/412343-Child-Care-Choices-of-Low-Income-Working-Families.PDF

22 López, M., Grindal, T., Zanoni, W., & Goerge, R. (2017). Hispanic Children’s Participation in Early Care and Education: A Look at Utilization Patterns of Chicago’s Publicly Funded Programs. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/hispanic-childrens-participation-in-early-care-and-education-a-look-at-utilization-patterns-of-chicagos-publicly-funded-programs/

23 Crosby, D., & Mendez, J. (2017). How Common Are Nonstandard Work Schedules Among Low- Income Hispanic Parents of Young Children?. National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. https://www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/how-common-are-nonstandard-work-schedules-among-low-income-hispanic-parents-of-young-children/

24 Sandstrom, H., & Chaudry, A. (2012). “You have to choose your childcare to t your work”: Childcare decision-making among low-income working families. Journal of Children and Poverty, 18(2), 89–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/10796126.2012.710480

25 Amadon, S., Borton, J., Lin, Y.-C., Madill, J., Ventura, I., & Xie, G. (2022). NSECE Snapshot: Employment Experiences of the 2019 Center-based Child Care Workforce during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Key Findings by Race and Ethnicity. OPRE Report #2022-291. Office of Planning, Research, and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/opre/report/nsece-snapshot-employment-experiences-2019-center-based-child-care-workforce-during-0

26 Lee, E. K., & Parolin, Z. (2021). The care burden during COVID-19: a national database of child care closures in the United States. Socius, 7. https://doi.org/10.1177/23780231211032028

27 Improving Child Care Access, Affordability, and Stability in the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF), 81 Fed. Reg. 45022, (July 13, 2023). https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/07/13/2023-14290/improving-child-care-access-affordability-and-stability-in-the-child-care-and-development-fund-ccdf