Jan 27, 2021

Research Publication

Disruptions to Child Care Arrangements and Work Schedules for Low-Income Hispanic Families are Common and Costly

Authors:

Overview

Child care is a critical support for working families that allows parents to pursue opportunities for employment and economic mobility.1,2 Child care’s vital role in the lives of families and in the overall economy is reflected in federal and state programs such as the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG) that aim to improve low-income families’ access to care options that support parents’ work efforts.3 A key premise of these programs is that families should have access to care arrangements that can both accommodate the needs of parents and children and that coordinate well with parents’ work lives. Yet research consistently shows that many parents encounter challenges when trying to coordinate employment and child care schedules, particularly for those in low-wage jobs.4,5,6

The realities of low-wage jobs—which include short notice of work hours, regularly shifting schedules, and last-minute shift changes—can make it difficult for families to coordinate child care and work. Such difficulties can lead to disruptions. For example, when children are sick, transportation issues arise, or providers are unavailable to cover a work shift, parents or other household members may need to find alternate care arrangements or miss work time. These care-work disruptions may be experienced differently by various racial/ethnic groups, given differences in household, work patterns, and child care utilization characteristics.

In this brief, we estimate the prevalence of care-work disruptions and their consequences for parents’ work in low-income households (defined as incomes below 200 percent of the federal poverty threshold), examining how both the prevalence and consequences of disruptions may differ for immigrant Hispanic,a nonimmigrant Hispanic, Black, and White households. We draw on data from the 2012 National Study of Early Care and Education (NSECE) focusing on households with children younger than age 13 and at least one employed caregiver (i.e., households at risk of experiencing disruptions and the target age population for federal child care subsidies). In supplemental analyses, we examine disruptions for the subsample of households with children younger than age 6 to explore whether the coordination of child care and work differs for children not yet in (or just entering) formal schooling.

Key Findings

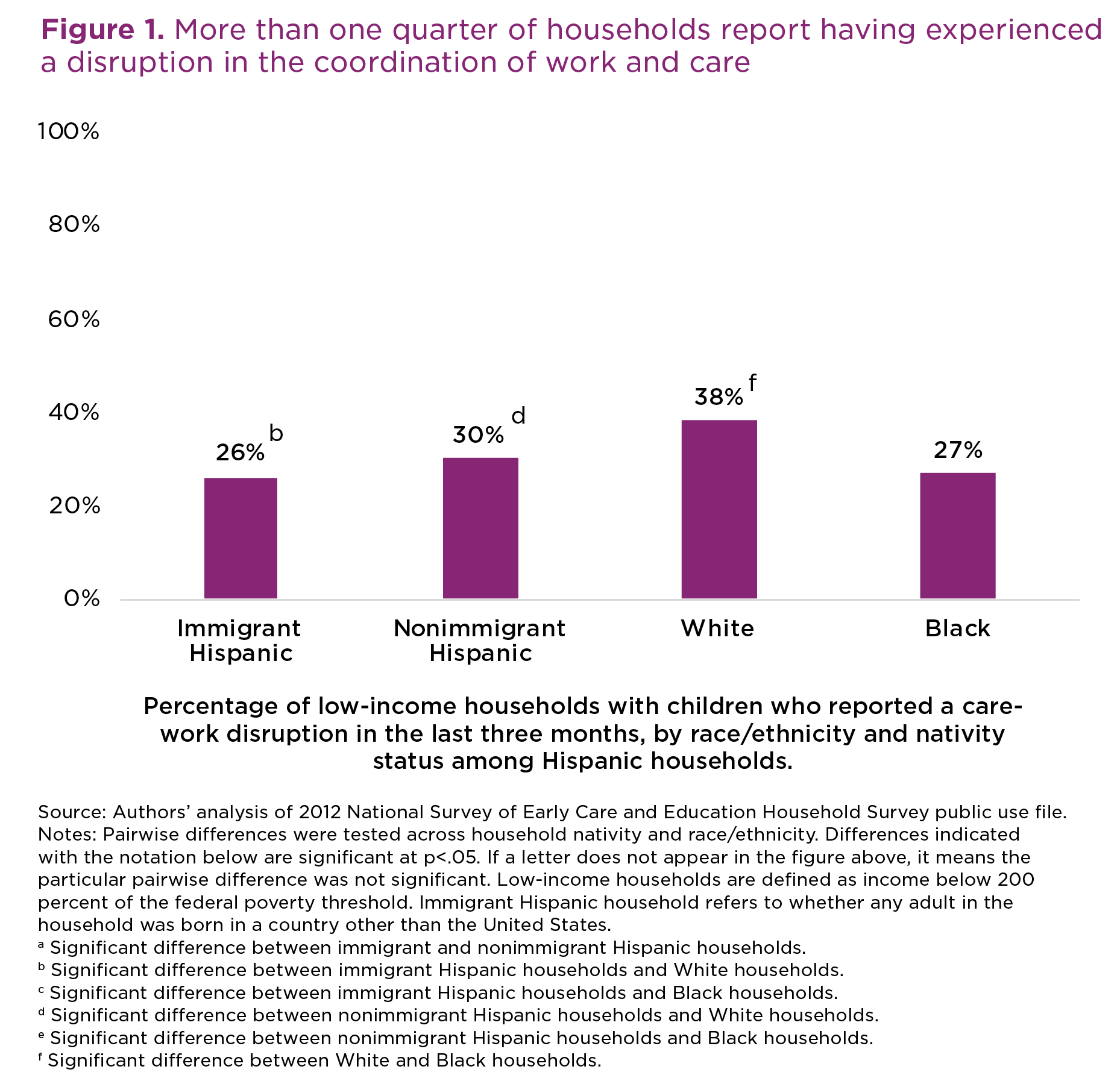

Across all racial/ethnic groups examined, we find that care-work disruptions are common across low-income households with children. More than one quarter of households report experiencing a disruption in the coordination of work and care in the last three months. To deal with such disruptions—for example, a child getting sick or a provider being unavailable—households report having to adjust their employment, either by missing work or working reduced hours, or to adjust their care arrangements (e.g., making special arrangements).

- Among low-income households who reported a disruption, these disruptions were frequent. Over the course of a calendar year, we estimate that low-income households who experience disruptions do so at least 20 days on average.

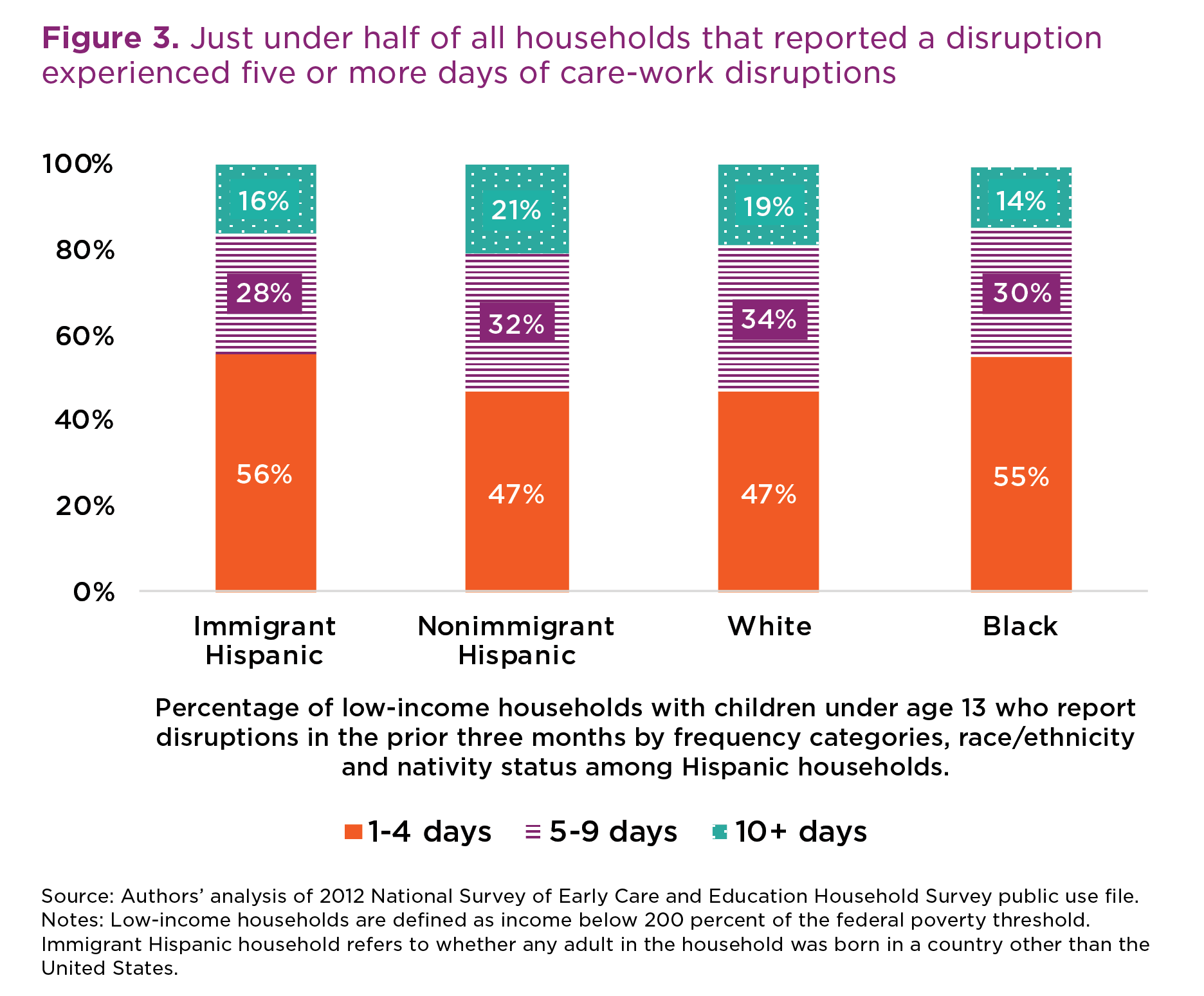

- Over a three-month period, nearly half of all households that reported a disruption said they had experienced this on five or more days during this period. This is the equivalent of experiencing disruption for a total of one work week or more during each quarter or three-month period.

- More than 1 in 10 households reported that disruptions happen very frequently, on 10 or more days during the three-month period or the equivalent of two work weeks per quarter.

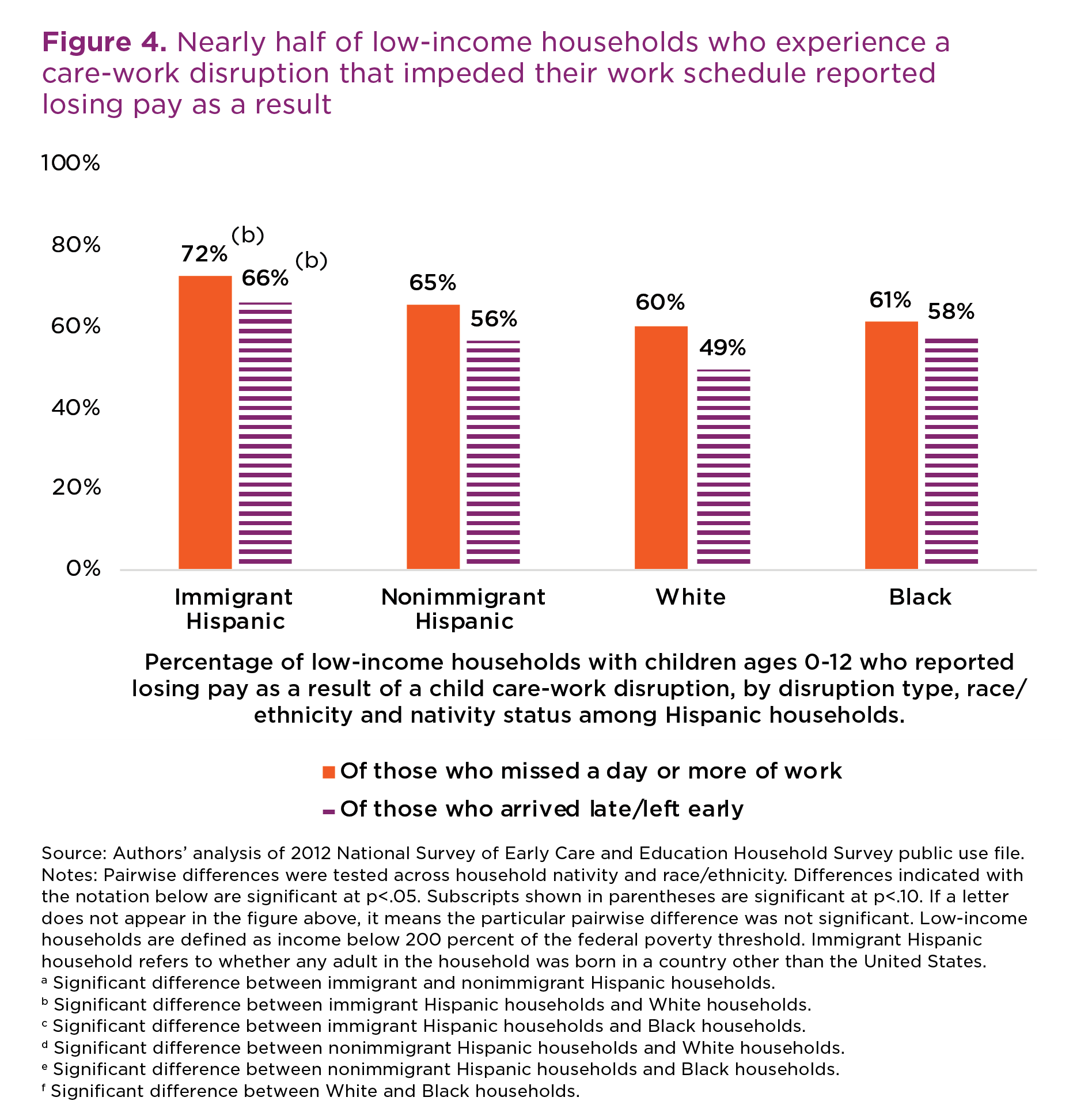

- Among low-income households who reported a disruption, the associated economic impact was sizable. Nearly half of those low-income households who experienced a disruption that impeded their work schedule lost pay as a result.

- Among those households that reported missing a day of work, at least 60 percent across racial/ethnic groups lost pay as a result.

- This is also true for those who reported arriving late or leaving early from work; at least 49 percent of these households across racial/ethnic groups lost pay as a result.

- We also observed some racial/ethnic differences in both the prevalence and consequences of disruptions. Low-income White households were most likely to report experiencing at least one disruption, while low-income immigrant Hispanic households were least likely to report experiencing some types of disruptions.

- Adults in low-income White households were significantly more likely to report experiencing a disruption in the last three months (38%) than immigrant Hispanic (26%), nonimmigrant Hispanic (30%), and Black (27%) households.

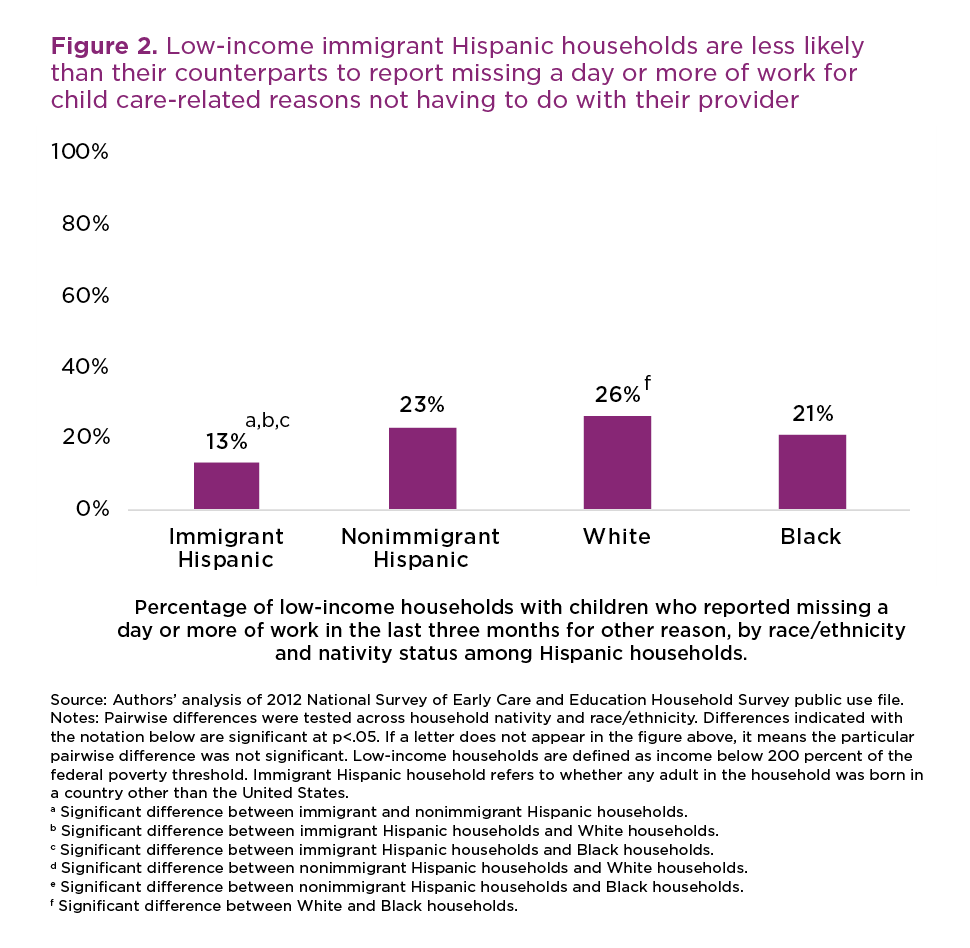

- Adults in low-income immigrant Hispanic households were significantly less likely to miss work because a child was sick (13%) than their nonimmigrant Hispanic (23%), White (26%), and Black counterparts (21%).

- Adults in low-income immigrant Hispanic households were also significantly less likely than their nonimmigrant Hispanic and White counterparts to report needing to make a special arrangement for care or to report working from home in the last month for child care-related reasons.

- In general, we find a pattern of results among the subsample of households with children younger than age 6b that is similar to the results reported above for the full sample of all households with children from birth to age 12, with one exception.

- Among households with children under age 6, adults in low-income immigrant Hispanic households (73%) were significantly more likely than adults in White households (54%) and nonimmigrant Hispanic households (48%) to lose pay if they were late to work or left early due to a disruption in care.

Background

Child care and employment are interconnected for many families with low incomes in the United States. In many low-wage jobs, workers have little autonomy or control over their work schedules and experience a range of challenges, including short notice of work hours, regularly shifting schedules, and last-minute shift changes.5,7,8 This often means that parents need child care options that are both reliable and flexible. Child care that is unstable or inflexible can have significant consequences for low-income parents’ employment. Low-wage jobs tend to be less accommodating when unpredictable care challenges arise—for example, when providers are unavailable due to illness or vacation or when children cannot attend their regular care arrangements because they are sick. Research on care-work disruptions has shown that these interruptions can result in work absences9 and job termination.10,11 Navigating these disruptions also entails additional stress for families.6,7 The consequences are also felt within the broader economy. Analyses conducted across multiple states show losses of millions of dollars in revenue due to worker absence and employee turnover that result from breakdowns in families’ child care arrangements.12

Relative to their counterparts from other races or ethnicities, Hispanic families with low incomes may experience care-work disruptions in unique ways based on differences in their household structure, job characteristics, and the child care providers who serve them. Hispanic families are likely to have a relatively high need for child care that supports parents’ work. For example, prior research finds that most low-income Hispanic families have an employed adult in the household,13 and that Hispanic and Black parents have lower incomes, on average, than White and Asian parents at similar levels of employment.14 In addition, as is common for many parents in the low-wage workforce, a majority Hispanic parents with young children and low incomes work early morning (5:00 to 8:00 am), evening (6:00 to 12:00 pm), and weekend hours as part of their schedules.15 Yet child care centers that serve high proportions of Hispanic children are less likely than other centers to offer full-time, evening, weekend, and/or flexible care hours.16 These findings may signal a disconnect between the availability of child care and the needs of working Hispanic families. At the same time, low-income Latino households have potential resources that may support their ability to navigate the coordination between employment and child care. For example, many Hispanic children in low-income households have two parents at home,17 and immigrant Latina mothers are less likely than other mothers to be employed18—both of which might facilitate work-care coordination within households.

Overall, research highlighting the unique challenges that Hispanic households with low incomes may face in coordinating work and child care—along with research on the resources these households may be able to leverage—suggests that an examination of racial/ethnic differences in work-care disruptions is merited. Additionally, documented differences by nativity status among Hispanic households—such as household structure,13 child care utilization,19 and work schedule characteristics,15 all of which may influence child care and work arrangements—suggest that researchers should pay greater attention to how disruptions might be experienced differently by immigrant and nonimmigrant Hispanic households.

Data Source and Methodology

This brief uses data from the 2012 National Survey of Early Care and Education (NSECE). The NSECE is a group of four nationally representative, integrated surveys that examine the availability of center-based and home-based child care, the characteristics of providers and families, and child care utilization. The sample was drawn from all 50 states and the District of Columbia, and low-income communities were oversampled. The data presented here were drawn from the Household Survey of the NSECE, which interviewed an adult member of households with children under age 13 regarding household demographics, employment information and schedules of adults, and care usage by children.

Our analysis focused on low-income households, defined as having an annual income below 200 percent of the federal poverty threshold, with children under age 13 who report using child care for any child in the home, and who have at least one caregiver who was employed. The analytic sample includes 4,813 households, including 2,196 Hispanic households (1,586 immigrant households and 610 non-immigrant households), 1,562 non-Hispanic White households, and 1,055 non-Hispanic Black households; more information on the methodology can be found below. We also examined a subsample of households whose youngest child is under age 6 (n=2,244); these families may or may not have older children within the household. This subsample makes up 47 percent of the overall sample.

Descriptive analyses were conducted to explore various types of disruptions to child care and the associated consequences for parents’ work. The analysis compared Hispanic households with young children, separately by household nativity status,c to non-Hispanic White and Black households. Non-Hispanic Asian, Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander, and American Indian or Alaska Native households were excluded due to small sample sizes. Data are presented for four household groups: 1) Hispanic immigrant households, 2) Hispanic nonimmigrant households, 3) White (non-Hispanic) households, and 4) Black (non-Hispanic) households.

These analyses were conducted for the household groups presented above with children from birth to age 13, as well as for the subsample of households with at least one child age under age 6. We conducted tests of statistical significance of mean differences between household groups. Lettered notation (a-f) was used to indicate significant difference in pairwise comparisons. The analysis was conducted using Stata version 16 and sample weights were applied following guidance from the NSECE Household Data File Codebook.20

Definitions

Experience of disruption. This variable was created to capture an interruption to the established child care and work arrangement in the last three months for any reason, for any household member who is the parent or caregiver of a child younger than age 13. The reported disruption is at the household level (rather than the individual level), so may reflect disruptions to the work activity of one or more adults and/or the care of one or more children. The type of disruption and impetus for the disruption are described below in greater detail.

Type of disruption. We made indicator variables for each type of disruption, which were based on parents’ reports of the specific disruption to their child care and work arrangement—whether they made special arrangements, worked from home, arrived late or left work early, or missed a day or more of work. Indicator variables capture whether any adult in the household experienced the specific disruption in the last three months, except for the worked from home disruption, which was only asked for the prior month.

Reason for disruption. For each type of disruption listed above, respondents reported on whether the disruption was for a provider reason or other reason. Provider reasons for disruption included child care provider sickness, vacation time during a non-holiday, or lack of availability. Other reasons for disruption included child sickness, a transportation-related reason, or another child care-related reason. The one exception to this response scheme is that the item about arriving to work late or leaving early asked simply about the frequency with which this happened “for child care responsibilities.”

Financial consequence of disruption. This category captures whether any household member who reported a child care work disruption lost pay as a result of the disruption. Specifically, those who reported missing a day of work or arriving late or leaving work early were asked whether they lost pay as a result.

Household ethnic-racial composition.d Household ethnic-racial composition refers to the reported ethnic-racial identity of all household members. Hispanic households in the NSECE are those in which the respondent reported that all household members identify as Hispanic (regardless of racial identity). Hispanic, non-Hispanic White, and non-Hispanic Black ethnic-racial groups are included in this brief. The terms White households and Black households are used for simplicity.

Household nativity status. Household nativity status refers to whether any adult in the household was born outside the United States. A household with one adult member born in a country other than the United States was labeled as an immigrant household. Nonimmigrant households are those in which all adults in the household were born in the United States.

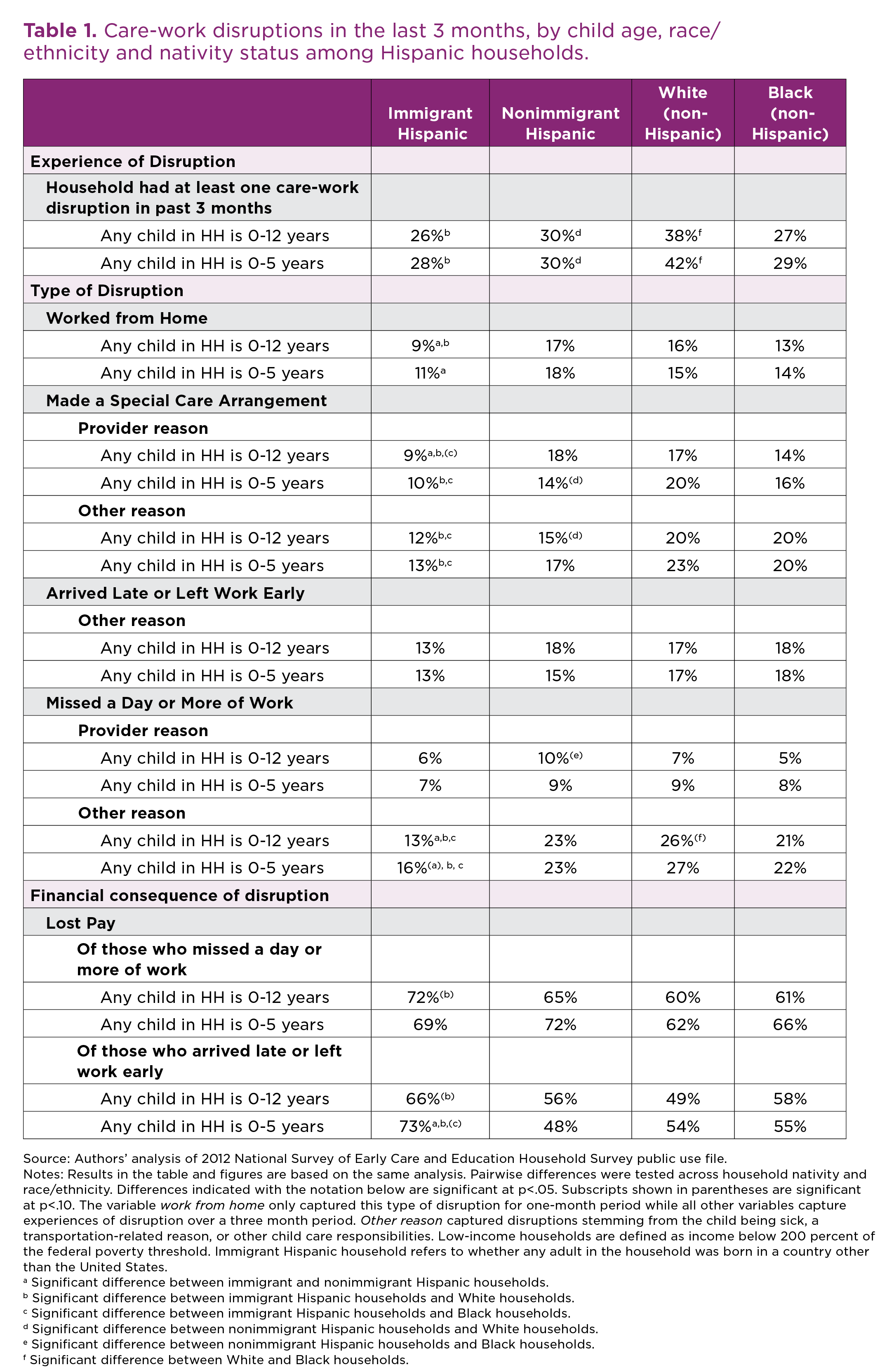

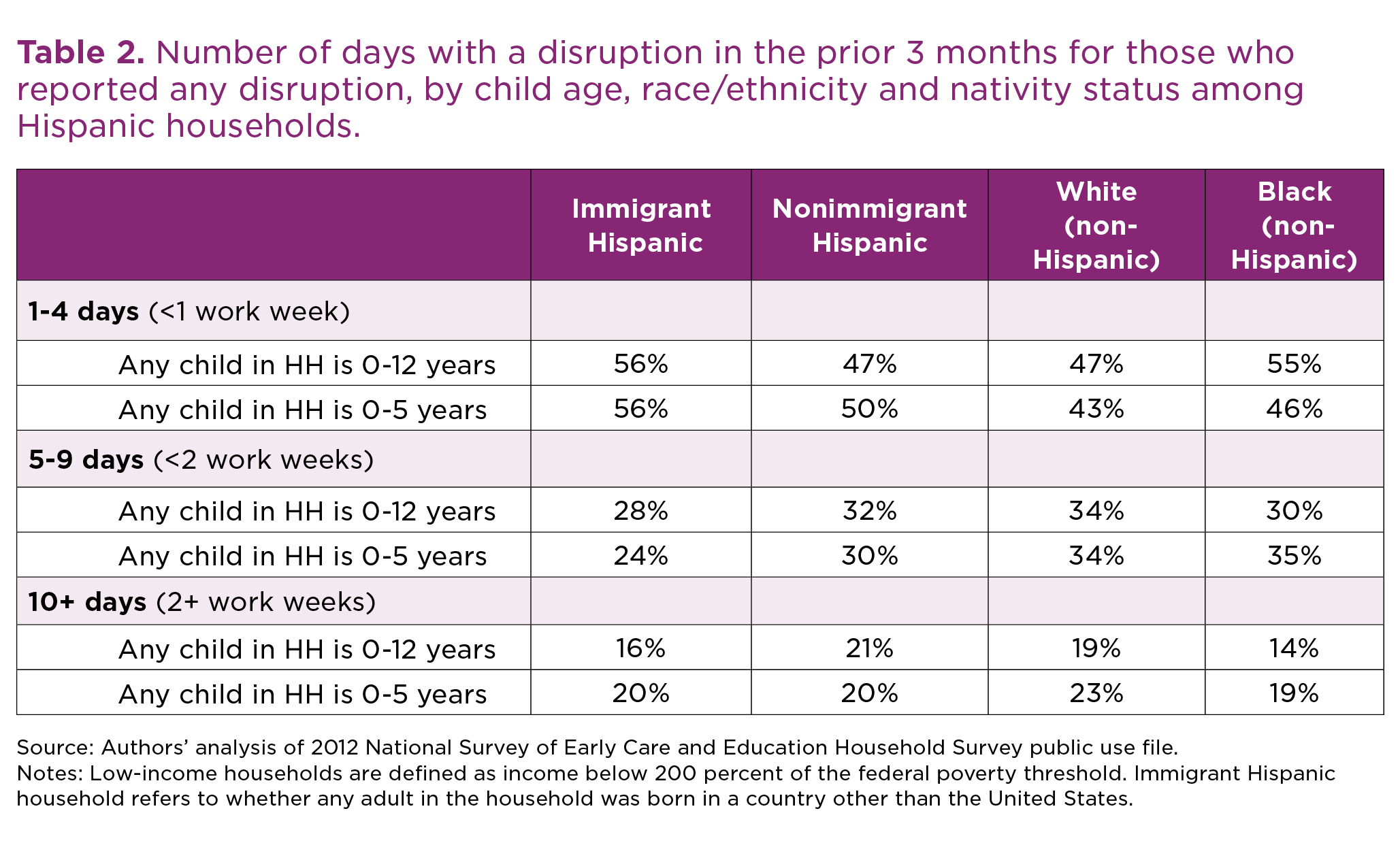

Weighted descriptive statistics on disruptions to work or child care arrangements for households with children from birth to age 12 are presented in tables 1 and 2.

c Only nonimmigrant White and Black households were included in the sample given the small number of White and Black households with immigrant adults (n=84 and n=129, respectively).

d Multi-racial and multi-ethnic households in which all members do not similarly identify as either Hispanic, non-Hispanic White, or non-Hispanic Black are not included in the current analysis, which limits our understanding of disruptions for these households.

Results

Experience of disruption. Care-work disruptions are common among all low-income households with children younger than age 13 included in the study (see Figure 1). Caregivers in White households (38%) are significantly more likely than those in immigrant Hispanic (26%), nonimmigrant Hispanic (30%), and Black households (27%) to report a disruption in the last three months. The pattern of findings for the subsample of low-income households with children younger than age 6 who reported a disruption was similar to the overall sample (see Table 1).

Worked from home. Approximately 9 percent of parents and caregivers from immigrant Hispanic households reported working from home to cover child care. This is a significantly lower percentage than among nonimmigrant Hispanic (17%) and White households (16%), but not significantly lower than among Black households (13%).

Made special arrangements. Parents and caregivers in Hispanic immigrant households (9%) were significantly less likely than those in Hispanic nonimmigrant (18%) or White households (17%) to have made a special care arrangement because their care provider was unavailable; the difference compared to Black households (14%) approached the level of statistical significance. For special arrangements made for other reasons (e.g., child illness or transportation issues), we found that immigrant Hispanic households (12%) were significantly less likely than White (20%) and Black households (20%) to make special arrangements. We also found that nonimmigrant Hispanic households (15%) were less likely than White households (20%) to make special arrangements; this difference approached significance.

Arrived late or left work early. Overall, all low-income households reported similar rates of missing work time for a child care-related reason—ranging from 13 to 18 percent of households, depending on race/ethnic composition of the household or nativity status among Hispanic households. There were no significant differences regardless of race/ethnic composition or nativity status among Hispanic households for missing work time for a child-care related reason.

Missed a day or more of work. Across households with children from birth to age 12, 5 to 10 percent of households reported missing at least one day of work because child care arrangements fell through. Among those that missed work because of another reason, such as child sickness or a transportation-related issue, immigrant Hispanic households (13%) were significantly less likely to report missing a day or more of work than their nonimmigrant Hispanic (23%), White (26%), or Black (21%) counterparts (see Figure 2). Black households (21%) were less likely than White households (26%) to report having missed a day or more of work for child care-related reasons other than issues with the provider; this difference approached significance.

Frequency of disruption. Approximately half of low-income households reported experiencing four days or less of disruptions over a three-month period, with 47 percent of nonimmigrant Hispanic and White households and approximately 56 percent of Black and immigrant Hispanic households reporting one to four days of disruption (see Figure 3). We found that more than one quarter of low-income Hispanic, White, and Black households reported experiencing a care-work disruption from five to nine days over a three-month period. Finally, 14 to 21 percent of low-income households experienced 10 or more days of disruptions, the equivalent of two or more work weeks, during a three-month period. Overall, the pattern of findings for frequencies of disruptions for the subsample of low-income households with children whose youngest child was under age 6 was similar to findings for the overall sample of low-income households with children younger than age 13 (see Table 2).

Financial consequences of disruptions. Figure 4 reports the financial consequences for households that missed some amount of work time as a result of child care-related issues. The majority of low-income households who missed a day or more of work due to an unplanned child care-related issue lost pay, ranging from 60 to 72 percent of households. Caregivers from immigrant Hispanic households were more likely to lose pay than those from White households (72% and 60%, respectively); this difference approached significance. Similarly, many low-income households in which a caregiver reported being late to or leaving early from work reported losing pay, ranging from 49 to 66 percent of households. Again, immigrant Hispanic households were more likely to lose pay when reporting arriving late or leaving early than were White households (66% and 49%, respectively); this difference approached significance. The pattern of findings for the financial consequences of disruptions among the subsample of low-income households with children whose youngest child was under age 6 was similar to the overall sample of low-income households with children younger than age 13 (see Table 1).

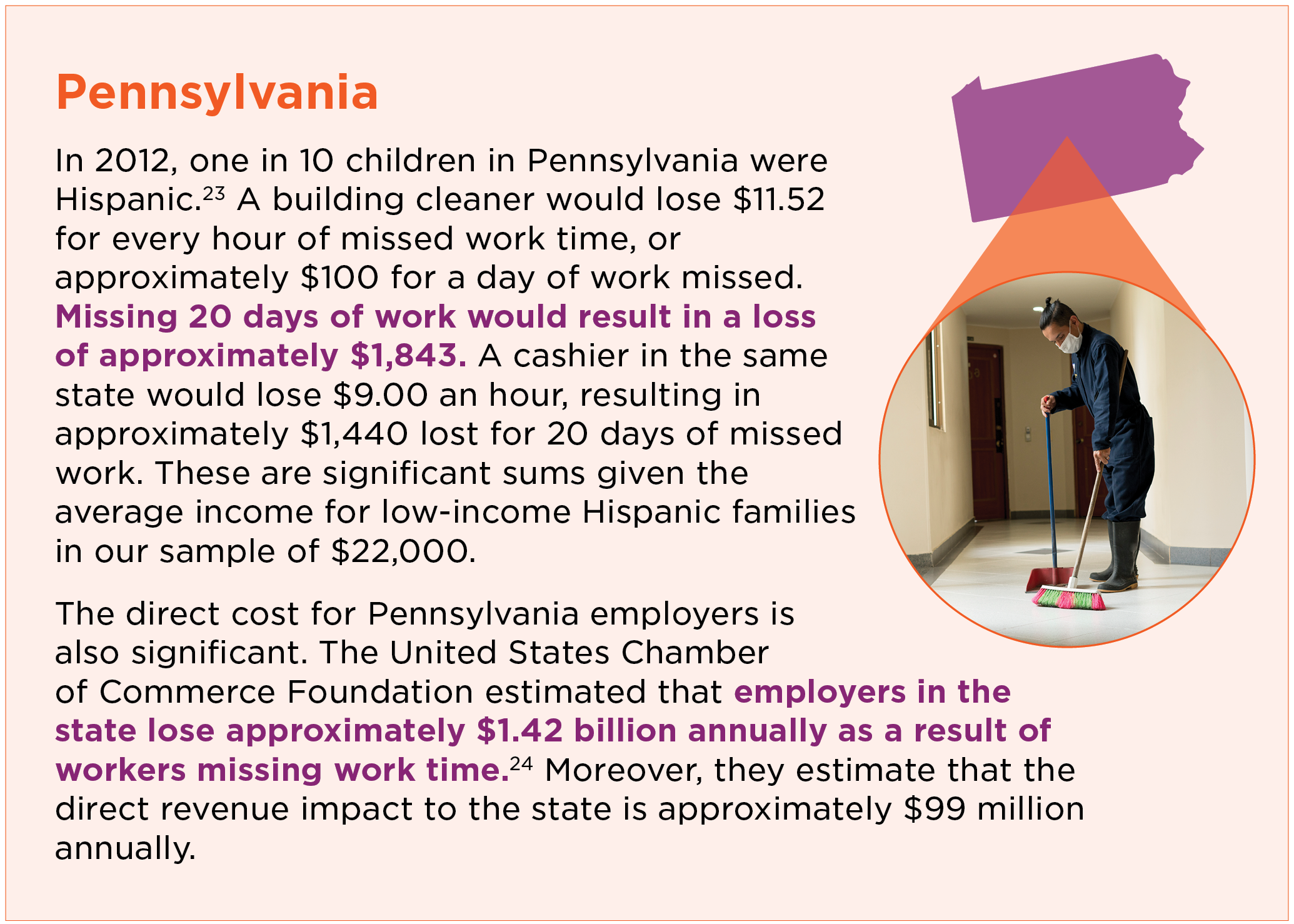

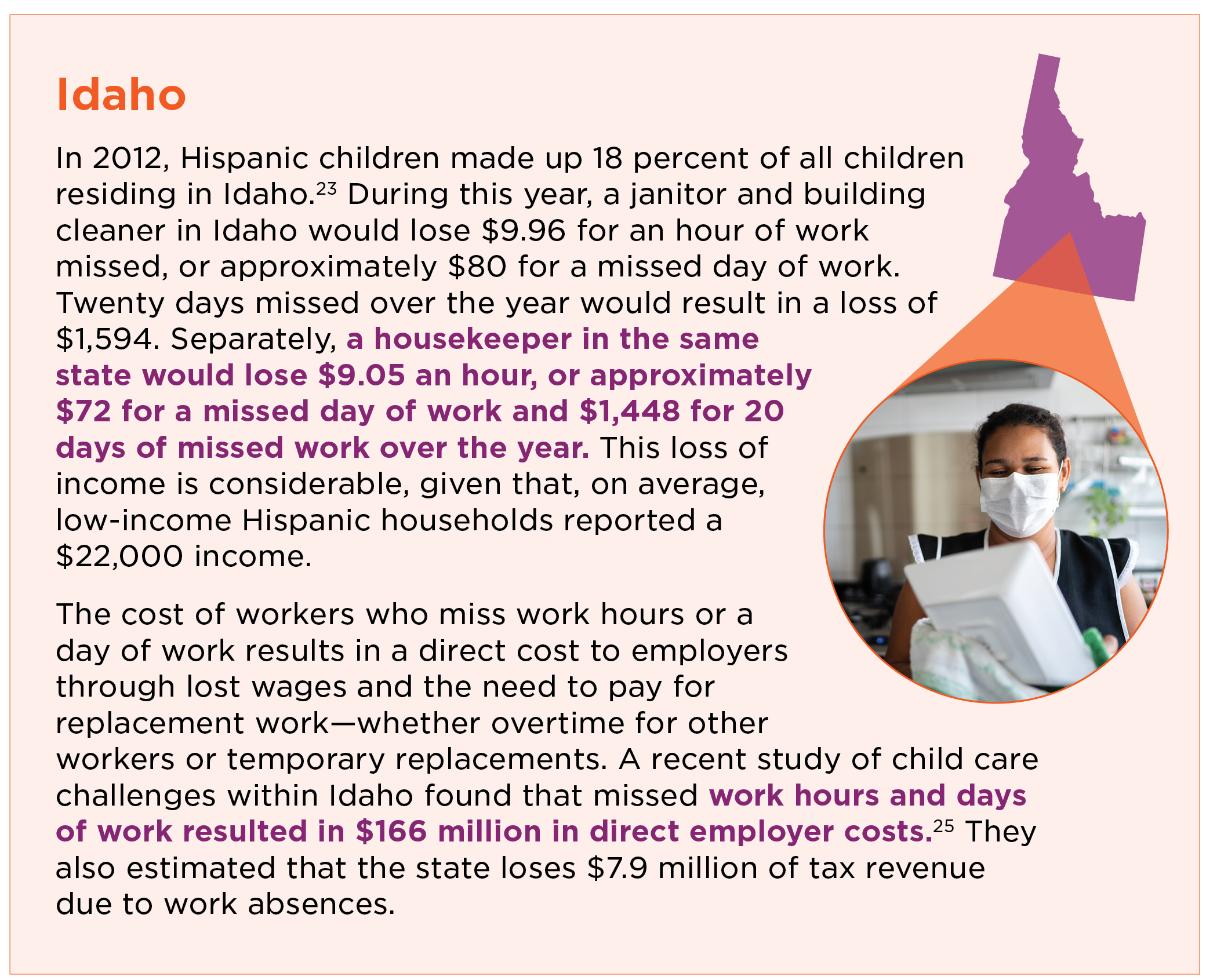

Taken together, our findings about the frequency and consequences of missed work suggest that, conservatively, many households miss the equivalent of at least a week of work and earnings over a three-month period because of a child care need, or approximately 20 days over the course of a year. As just one example of what this means for families, a building cleaner in Pennsylvania would lose $1,843 in missed wages in one year (based on wages during 2012, the year of the study). In Idaho, a housekeeper would lose approximately $1,448. These are significant sums for low-income households; as a reference, Hispanic families in our sample, across nativity status, reported an average income of approximately $22,000 dollars per year. The economic consequences for workers, industries, and states are further explored in the subsection below.

Estimating the costs of care-work disruptions for households, employers, and state revenue: A look at two states.

The following profiles further illustrate the economic consequences of care-work disruptions, showing the costs of disruptions for low-income Hispanic families in two states (Pennsylvania and Idaho), and for the states and their economies. For each state, we first calculate the potential direct cost of disruptions to low-income Hispanic households. To complement this analysis, we use data from the United States Chamber of Commerce Foundation to present the direct cost of disruptions for employers and for state revenue.

Direct cost to households is presented through the potential loss of median wages for Hispanic workers across two common occupations among low-income workers.21,22 The resulting loss is calculated for a missed week of work, given our finding that—among those households that experience disruptions—almost half of Hispanic households reported five days or more of disruptions in a three-month period, or 20 days on average over the course of a calendar year. The cost of workers who miss work time or a day or more of work results in a direct cost to employers through lost wages and the need to pay for replacement work. Moreover, state revenue may be impacted through reduced taxable income or reduction in spending by families experiencing disruptions.

Discussion

Coordinating employment with the need to arrange care for young children is challenging for many parents, especially in the context of low-wage work. Our findings highlight the fragile relationship between child care and work for many low-income families, and the costliness of that fragility. We found that over one quarter of low-income households reported that coordination between child care and work arrangements had broken down in the last three months. Some of the time, households appeared to deal with disruptions by making special care arrangements for children or having an adult work from home. Other times, these disruptions caused an interruption to work activity and led caregivers to miss work. These disruptions are frequent, and the associated economic impact was sizable for low-income households.

The disruptions that low-income households experience are likely to accumulate over time. We find that, among Hispanic, White, and Black low-income households that report a disruption, roughly half (44 to 53%) experience disruptions five or more days over a three-month period. In other words, low-income households who experience disruptions can expect them to occur, on average, the equivalent of at least one work week each quarter and at least 20 days over the course of a calendar year. Alarmingly, more than one in 10 low-income households who experienced any disruption reported that these events had happened on 10 or more days (or the equivalent of two or more work weeks) in the past three months. The frequency of these disruptions may result in changes to work: Families may seek alternative employment that better supports their child care accommodations, or family members may be terminated by their employer;10,11 for families already struggling to make ends meet, either outcome may result in a loss in wages.

The prevalence of care-work disruptions among low-income households and the high frequency with which some households experience these disruptions augment previous research on the precarious nature of work for families with low incomes. Prior work has shown that some working parents report carefully considered approaches to addressing other types of interruptions to child care, such as transitions in child care settings for children,6 and that families may have multiple back-up providers to facilitate their work arrangements.26 This body of research is mirrored in our findings that households report making special care arrangements or having a household member work from home when child care becomes disrupted. Our findings add to the field’s understanding of the many strategies that low-income families utilize to maintain delicate arrangements of care that maintain their work; previous research has shown that, across low-income households, nearly one third of households have two or more care arrangements.27

Despite these multiple arrangements, though, a sizable percentage of households reported being absent from work or arriving to work late or leaving early as a result of a disruption, suggesting that families cannot always mitigate the more consequential forms of disruption. Moreover, previous research has highlighted how characteristics of low-income jobs—including non-standard schedules, unstable schedules, or multiple jobs held—can create multiple stressors that may affect parent and child well-being.18,28,29 The high frequency of disruptions for many families in our sample suggests that care-work disruptions may be an additional and consistent stressor for low-income families and should be examined as such.

Despite these multiple arrangements, though, a sizable percentage of households reported being absent from work or arriving to work late or leaving early as a result of a disruption, suggesting that families cannot always mitigate the more consequential forms of disruption. Moreover, previous research has highlighted how characteristics of low-income jobs—including non-standard schedules, unstable schedules, or multiple jobs held—can create multiple stressors that may affect parent and child well-being.18,28,29 The high frequency of disruptions for many families in our sample suggests that care-work disruptions may be an additional and consistent stressor for low-income families and should be examined as such.

Lost pay is also a common and meaningful consequence of care-work disruptions. Among households that reported arriving to work late or needing to leave early for a child care-related reason, nearly half reported losing pay as a result. Among households with a caregiver who missed an entire day or more of work because of a child care need, six in 10 lost pay. As illustrated in the subsection of this brief that discusses economic consequences for families, a building cleaner in Pennsylvania would lose $1,843 in missed wages in one year, as one example.

In general, we found few differences among the groups examined within our sample. That is, the experiences of disruptions and consequences were similar for Hispanic, Black, and White households—with two exceptions. First, low-income White households were more likely to report a disruption than low-income nonimmigrant and immigrant Hispanic and low-income Black households. Second, immigrant Latino households with low incomes were significantly less likely to report experiencing specific care-work disruptions than their nonimmigrant Hispanic, White, and Black counterparts.

This lower likelihood of experiencing disruptions among low-income immigrant Hispanics could be attributed to multiple factors. First, children in low-income Hispanic families are more likely to have a mother in the home who does not report being employed, relative to their nonimmigrant Hispanic, White, and Black counterparts.18 In addition, children in low-income Hispanic families are more likely to live in two-parent households and in larger households than those with only nonimmigrant Hispanic parents and their White and Black peers.13 These larger households may allow greater flexibility to respond to situations that may precipitate disruptions or create a greater perception of social support, which is associated with reduced disruptions.9 Other research has identified that low-income Hispanic families are more likely to utilize paid, home-based care for their non-school-aged children;27 these providers may be more willing to care for sick children, which are one of the reasons for reported care-work disruptions. Third, low-income immigrant Hispanic households were more likely to report lost pay as a result of disruptions, relative to nonimmigrant Hispanic, White, and Black households—particularly for the subsample of households with children younger than age 6. The greater flexibility to accommodate potential disruptions, described above, may result in a greater likelihood that the disruptions that do occur are of the most consequential kind that result in lost pay. Alternately, the lower likelihood of experiencing disruptions may also be attributed to differences in work between immigrant and nonimmigrant populations. For example, recent research into the job characteristics of low-income Hispanic parents found that nearly one third of immigrant fathers had three or more job characteristics shown to negatively impact family well-being, as compared to one quarter of U.S.-born Hispanic fathers.18 Other reasons for the lower likelihood of experiencing disruptions may include characteristics common to the industries in which immigrant Hispanic household members are employed.

The current findings illustrate the need for a greater focus on work flexibility in the employment opportunities common to families with low incomes. Much of the care-work disruptions literature focuses on how child care stability and flexibility impact parents’ ability to work; this is also the primary focus of the NSECE data examined in this study. However, this work does not fully capture the interrelated nature of these systems and exposes an underlying assumption that the workplace cannot be adapted to better meet child care needs. Instead, the burden to be flexible is often placed primarily on families and child care arrangements. Nonetheless, workplace policy and practice can be adapted to increase the flexibility that families have to respond to potential sources of disruption. In a multivariate analysis, Henly and Lambert30 find that retail workers with greater input on their schedules had less work-family conflict, suggesting that adaptions to employment practices may reduce disruptions for low-income families. From individual businesses providing child care at the workplace to state paid sick leave policies—such as California’s Healthy Workplace Healthy Family Act—an increasing variety of templates can align work conditions to family needs.

Given the role of federal and state programs (such as CCDBG) in supporting parental employment, our finding that care-work disruptions are a relatively common experience for low-income families draws attention to program rules and regulations. The 2014 CCDBG reauthorization aims to increase stability for families and providers by requiring states, to the extent possible, to delink provider payments from children’s occasional absences.3 As of 2016, six states base subsidy payments on children’s enrollment rather than attendance, and another 10 states provide full subsidy payments as long as children have no more than five absences per month.31 As more states implement policy in response to the 2014 reauthorization, it will be important to assess their impact on disruptions.

The patterns found in these data also have relevance for concerns about the lack of accessible child care to support working families during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, which has disrupted both parents’ work and children’s care arrangements through changes in operations and closures. The pandemic has drawn the delicate coordination between work and child care into sharp relief, with Congress including over $3.5 billion to shore up child care and provide care to essential workers throughout the pandemic as part of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act.32

Conclusion

Given the frequency and associated economic consequences of care-work disruptions for low-income households with children younger than age 13, greater efforts across workplaces and child care providers are needed to address these disruptions, along with advances in federal and state policy. The critical role of child care for low-income families and the country’s economy and fiscal health suggests that mitigating care-work disruptions must remain a top priority as we emerge from and address the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Tables 1 & 2

Footnotes

a This brief uses the terms Hispanic and Latino interchangeably throughout.

b The analyses were conducted comparing the overall sample—low-income households with any children under age 13—with a subsample of households where the youngest child in the household is under age 6. While we also examined differences in disruptions for those low-income households with only children younger than age 6, these analyses were not included due to inadequate sample size (for example N ≈ 35 for immigrant Hispanic families with low incomes who report losing pay as a result of missing work time). Nonetheless, we find similar results when this subpopulation is analyzed, suggesting that patterns of care-work disruptions for low-income households do not vary by child age.

Suggested Citation

Ferreira van Leer, K., Crosby, D., & Mendez, J. (2021). Disruptions to Child Care Arrangements and Work Schedules for Low-Income Hispanic Families are Common and Costly. Report 2021-01. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. Retrieved from www.hispanicresearchcenter.org/research-resources/disruptions-to-child-care-arrangements-and-work-schedules-for-low-income-hispanic-families-are-common-and-costly

References

1 Bromer, J., & Henly, J. R. (2009). The work-family support roles of child care providers across settings. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 24(4), 271-288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2009.04.002

2 Lowe, E. D., & Weisner, T. S. (2006). “Child Care and Low-Wage Employment.” In Yoshikawa, H., Weisner, T. S., Lowe, E. D. (Eds.), Making it Work: Low-Wage Employment, Family Life, and Child Development (pp. 235-255). New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

3 Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) Program, 45 CFR section § 98. (2016). Retrieved from https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2016-09-30/pdf/2016-22986.pdf

4 Henly, J.R., & Lambert, S. (2005). Nonstandard work and child-care needs of low-income parents. In Bianchi, S. M., Casper, L. M., & King, R. B. (Eds.), Work, family, health, and well-being (pp. 473–492). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

5 Sandstrom, H., & Chaudry, A. (2012). “You have to choose your childcare to fit your work”: Childcare decision-making among low-income working families. Journal of Children and Poverty, 18(2), 89–119. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1080/10796126.2012.710480

6 Spiers, K. E., Vesely, C. K., & Roy, K. (2015). Is stability always a good thing? Low-income mothers’ experiences with child care transitions. Children and Youth Services Review, 53, 146-156. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.03.026

7 Perez, C., & Gould-Werth, A. (2019). It’s about time: How work schedule instability matters for workers, families, and racial inequality. The Shift Project. Retrieved from https://shift.hks.harvard.edu/its-about-time-how-work-schedule-instability-matters-for-workers-families-and-racial-inequality/

8 Swanberg, J. E., Watson, E., & Eastman, M. (2014). Scheduling challenges among workers in low-wage hourly jobs: similarities and differences among workers in standard- and nonstandard-hour jobs. Community, Work & Family, 17(4), 409-435. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2014.931837

9 Usdansky, M. L., & Wolf, D. A. (2008). When child care breaks down: Mothers’ experiences with child care problems and resulting missed work. Journal of Family Issues, 29(9). doi:1185-1210.10.1177/0192513X08317045

10 Dodson, L. (2006). After welfare reform: You choose your child over the job. Focus, 24(3), 25-28.

11 Gordon, R.A., Kaestner, R., & Korenman, S. (2008). Child care and work absences: Trade‐offs by type of care. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70, 239-254. doi:10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00475.x

12 U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation. (202). Untapped potential: Economic impact of childcare breakdowns on U.S. States. Retrieved from https://www.uschamberfoundation.org/reports/untapped-potential-economic-impact-childcare-breakdowns-us-states

13 Turner, K., Guzman, L., Wildsmith, E., & Scott, M. (2015). The complex and varied households of low-income Hispanic children. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. Retrieved from https://hispanicrescen.wpengine.com/research-resources/the-complex-and-varied-households-of-low-income-hispanic-children/

14 Baldiga, M., Joshi, P., Hardy, E., & Acevedo-Garcia, D. (2018). Data-for-equity research brief: Child care affordability for working parents. Diversitydatakids.org. Retrieved from http://www.diversitydatakids.org/sites/default/files/2020-02/child-care_update.pdf

15 Crosby, D., & Mendez, M. (2017). How common are nonstandard work schedules among low-income Hispanic parents of young children? Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. Retrieved from https://hispanicrescen.wpengine.com/research-resources/how-common-are-nonstandard-work-schedules-among-low-income-hispanic-parents-of-young-children/

16 Guzman, L., Hickman, S., Turner, K., & Gennetian, L. (2017). How well are early care and education providers who serve Hispanic children doing on access and availability? Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. Retrieved from https://hispanicrescen.wpengine.com/research-resources/how-well-are-early-care-and-education-providers-who-serve-hispanic-children-doing-on-access-and-availability/

17 Cabrera, N., & Hennigar, A. (2019). The early home environment of Latino children: A research synthesis. Report 2019-20-45. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. Retrieved from https://hispanicrescen.wpengine.com/publications/the-earlyhome-environment-of-latino-children-a-research-synthesis

18 Wildsmith, E., Ramos-Olazagasti, M. A., & Alvira-Hammond, M. (2018). The job characteristics of low-income Hispanic parents. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. Retrieved from https://hispanicrescen.wpengine.com/research-resources/the-job-characteristics-of-low-income-hispanic-parents/

19 Ansari, A. (2017). The selection of preschool for immigrant and native-born Latino families in the United States. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 41(4), 149-160. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2017.07.002

20 NSECE Project Team (National Opinion Research Center). (2020). National Survey of Early Care and Education (NCESE), [United States], 2010-2012. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research. doi: 10.3886/ICPSR35519.v13

21 Bucknor, C. (2016). Hispanic workers in the United States [report]. Center for Economic and Policy Research. Retrieved from https://cepr.net/images/stories/reports/hispanic-workers-2016-11.pdf

22 U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2012). May 2012 State Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates [Data file]. Retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/oes/tables.htm

23 Kids Count Data Center. (2020). Kids count data center: Child population by race in the United States [Data file]. Retrieved from https://datacenter.kidscount.org/data/tables/103-child-population-by-race?loc=1&loct=2#detailed/2/2-52/false/37,871,870,573,869,36,868,867,133,38/12/423,424

24 U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation. (2020). PA untapped potential: How childcare impacts Idaho’s state economy. Retrieved from https://www.uschamberfoundation.org/sites/default/files/EarlyEd_UntappedPotential_Pennsylvania.pdf

25 U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation. (2020). ID untapped potential: How childcare impacts Idaho’s state economy. Retrieved from https://www.uschamberfoundation.org/sites/default/files/EarlyEd_UntappedPotential_Idaho.pdf

26 Scott, E. K., London, A. S., & Hurst, A. (2005). Instability in patchworks of child care when moving from welfare to work. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 370-386. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/3600275

27 Crosby, D., Mendez, J., Guzman, L., & López, M. (2016). Hispanic children’s participation in early care and education: Type of care by household nativity status, race/ethnicity, and child age. Bethesda, MD: National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families. Retrieved from https://hispanicrescen.wpengine.com/?publications=hispanic-childrens-participation-in-early-care-and-education-type-of-care-by-household-nativity-status-raceethnicity-and-child-age

28 Li, J., Johnson, S.E., Han, W., Andrews, S., Kendall, G., Strazdins, L., & Dockery, A. (2014). Parents’ nonstandard work schedules and child well-being: A critical review of the Literature. J Primary Prevent, 35, 53–73. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-013-0318-z

29 Schneider, D., & Harknett, K. (2019). Consequences of Routine Work-Schedule Instability for Worker Health and Well-Being. American Sociological Review, 84(1), 82–114. Retrieved rom https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122418823184

30 Henly, J.R., & Lambert, S.J. (2014). Unpredictable Work Timing in Retail Jobs. ILR Review, 67(3), 986-1016. doi: 10.1177/0019793914537458

31 Office of Child Care (2016, Oct 19). Delinking provider payments and attendance. Retrieved from https://www.acf.hhs.gov/occ/resource/delinking-provider-payments-and-attendance

32 Johnston-Staub, C. (2020). COVID-19 and state child care assistance programs: Immediate considerations for state CCDF lead agencies. CLASP. Retrieved from https://www.clasp.org/sites/default/files/publications/2020/04/Updated%20%20COVID-19%20%26%20State%20Child%20Care%20Assistance.pdf

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Steering Committee of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, Julie Henly, and staff from OPRE for their feedback on earlier drafts of this brief, as well as Melissa Perez for her research assistance at multiple stages of this project.

Editor: Brent Franklin

Designer: Catherine Nichols

About the Authors

Kevin Ferreira van Leer, PhD, was a 2019 research scholar with the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, supporting research on early care and education. He is an assistant professor in the Child and Adolescent Development program at California State University, Sacramento. His research examines the social and cultural contexts that promote positive development and liberation for immigrants of color and their families, with an emphasis on how contexts influence the educational and caregiving experiences of Latinx immigrant families.

Danielle Crosby, PhD, is a co-investigator of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, co-leading the research area on early care and education. She is an associate professor in the Department of Human Development and Family Studies at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Her research focuses on understanding how social, economic, and cultural factors shape the educational experiences of young children in low-income families.

Julia Mendez, PhD, is a co-investigator of the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families, co-leading the research area on early care and education. She is a professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. Her research focuses on risk and resilience among ethnically diverse children and families, with an emphasis on parent-child interactions and parent engagement in early care and education programs.

About the Center

The National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families (Center) is a hub of research to help programs and policy better serve low-income Hispanics across three priority areas: poverty reduction and economic self-sufficiency, healthy marriage and responsible fatherhood, and early care and education. The Center is led by Child Trends, in partnership with Duke University, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, and University of Maryland, College Park. The Center is supported by grant #90PH0028 from the Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation within the Administration for Children and Families in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families is solely responsible for the content of this brief, which does not necessarily represent the official views of the Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, the Administration for Children and Families, or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Copyright 2020 by the National Research Center on Hispanic Children & Families